Hundreds of students gathered inside Swasey Chapel on the afternoon of Jan. 28, 1986, to grieve the loss of seven people they never met.

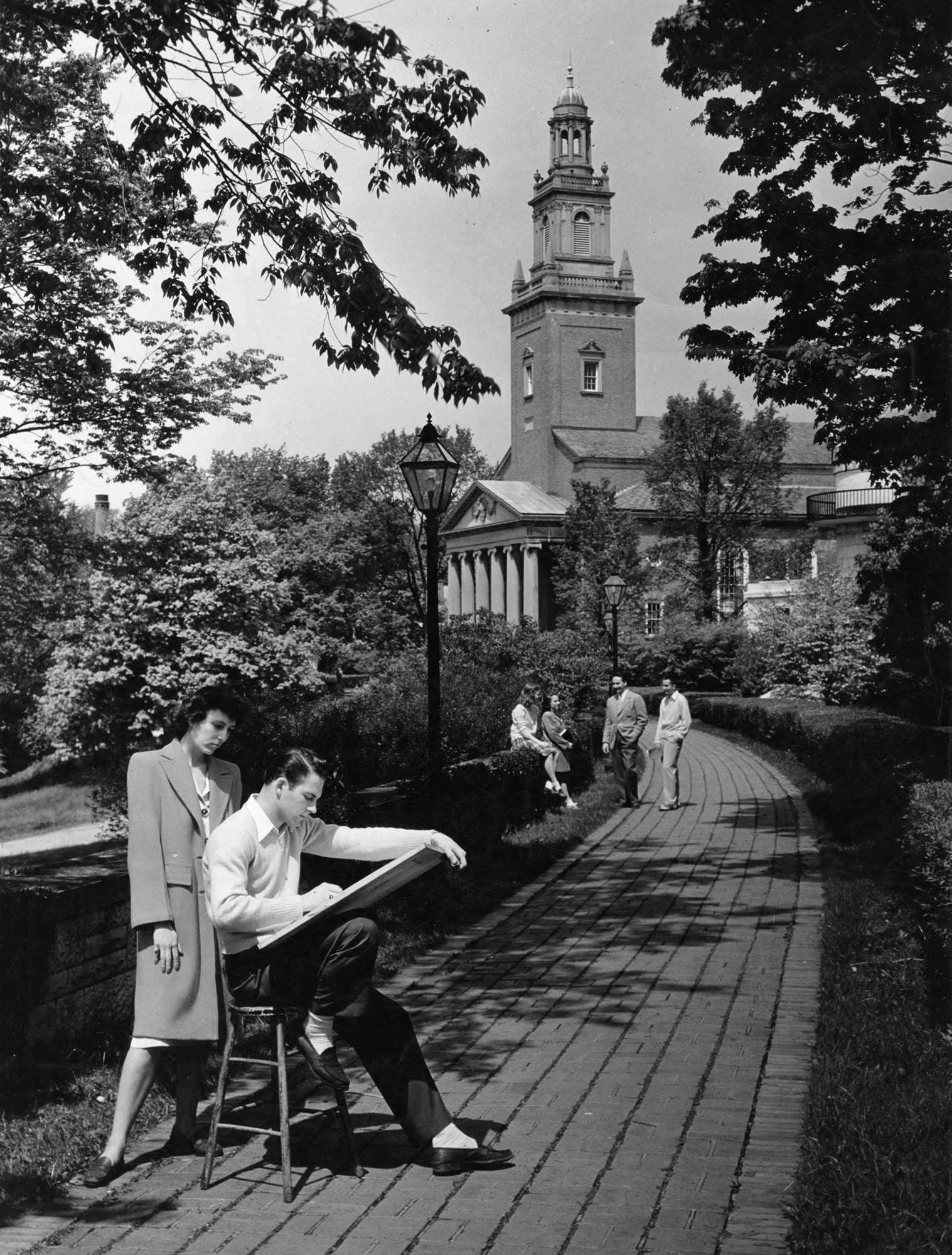

Fred Porcheddu-Engel ’87 was among the mourners who numbly traveled up Chapel Walk, entering the red-bricked campus landmark with its six Ionic columns. Minutes earlier, Porcheddu-Engel had watched liftoff of the space shuttle Challenger on a television in Slayter Hall only to see it explode 73 seconds into flight, killing all aboard.

As numbers swelled in the sanctuary, Porcheddu-Engel was struck by the instinctive nature of fellow students. No faculty member or administrator had advised them to meet in the chapel.

“These were the days before cell phones or email, a time when news traveled by word of mouth,” said Porcheddu-Engel, a longtime English professor at Denison. “But the impulse was we needed to experience this loss as a community. It was a very powerful moment, and it emphasized the importance of the chapel.”

In times of joy and sorrow, in days of celebration and remembrance, no place on campus has united Denisonians like Swasey Chapel, which commemorates its centennial anniversary in 2024. It remains the venerated centerpiece of the university.

Built by benefactor and trustee Ambrose Swasey as a house of worship, it exhibits the trait of many enduring venues — the ability to bend and repurpose itself to the ever-changing needs of its population.

Swasey is home to academic award convocations, weddings, and funerals. To the university’s gospel choir, chamber choir, and concert choir. To renowned authors, political speakers, and world-class musical performances and artistry.

The chapel’s greatest contribution, however, is the indelible memories it leaves students, faculty, and staff.

“We must salute the past as we move forward,” said David Woodyard ’54, who’s taught at Denison for more than 60 years and proposed to his wife, Joanne Adamson Woodyard ’55, outside Swasey Chapel. “For a lot of alumni, this place is where their life transpired and grew.”

Divine connection

Ambrose Swasey (1846-1937) earned honorary degrees from seven academic institutions, including Denison, without ever attending a university.

“All my brothers and sisters went to academies or colleges,” Swasey once said, “but my only schooling came from the little country grammar school” in Exeter, New Hampshire.

A teenage apprentice in machine works, Swasey displayed a remarkable aptitude for mechanical engineering. He was awarded 23 patents and, along with his business partner, Worcester Warner, founded a company that specialized in machine tools. The duo later gained international acclaim for designing astronomical instruments.

As his fortune grew, so did Swasey’s desire to spread his wealth. He gave generously to academic institutions and religious organizations. Denison, founded as denominationally Baptist, satisfied both criteria.

Swasey and his wife, Lavinia, were devout Baptists. He had grown up hearing tales of his ancestors being driven out of Salem, Massachusetts, because of their religious convictions.

Much like business magnate and fellow Baptist John D. Rockefeller, who also donated to Denison, Swasey needed little encouragement to support the university after relocating his company from Chicago to Cleveland.

“There were a fair number of colleges established by the Baptists,” said Dennis Read, associate professor emeritus in English. “If you were a Baptist and you made some money, there was an obligation to support these institutions.”

Swasey joined the Denison Board of Trustees in 1897, becoming its president in 1923 and serving as its honorary president until his death. He financed a men’s gymnasium (now Bryant Arts Center) in 1905 and the building of Swasey Observatory in 1909. When the university unveiled its “Greater Denison” plan for campus expansion, he was the first to reach for his checkbook.

“They needed a chapel, which was central to any Denison student of that era,” Read said. “Swasey stepped forward.”

Even as the chapel’s cornerstone was being laid in 1922, Swasey was increasing his investment. He made possible the purchase of an echo organ and a bell tower, containing a carillon of 10 bells in honor of Lavinia, who died in 1913.

The chapel, which seats more than 950 people and mirrors Sir Christopher Wren style English churches, was dedicated April 18, 1924. It cost $400,000.

“I think of Swasey as a place where someone can have a spiritual experience, a connection with the divine,” said Timothy Carpenter, Denison’s gospel choir leader and Christian life coordinator. “It is a magnificent gift to this campus.”

America’s secret stashes

Ambrose Swasey didn’t live long enough to witness the chapel’s greatest contribution to his nation. Anticipating war and fearing an enemy air attack, the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., selected five secret locations in 1941 to store its most precious possessions.

Denison was chosen among the sites, housing cultural treasures in the chapel, Doane Library, and Life Science building. About 1,200 wooden cases, weighing roughly 140 pounds each, were unloaded by students sworn to secrecy. The material was guarded around the clock by four men employed by the government and tasked with monitoring barometric readings to ensure the goods weren’t damaged by the humid central Ohio summers.

The three most priceless documents — the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Magna Carta — were shipped to the Fort Knox Bullion Depository in Kentucky. Denison received the next tier of valuables, including presidential papers, notebooks of famous authors, musical instruments, and the original telegram sent by Samuel Morse: “What hath God wrought?”

The cargo was safely returned to the Library of Congress in 1944. In his letter to Denison president Kenneth Brown, Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish wrote: “You will share our thankfulness that the long and difficult journey is completed without accident, and you will know … how much we owe to you and your colleagues and to the University for your generosity of mind and spirit.”

Staying power

“It is my earnest desire that this chapel shall be used only for such services as directly contribute to the worship of God and the upbringing of Christian character.”

Those words are inscribed on a wall-mounted relief in the chapel’s foyer. It’s a sentiment John Jackson, associate professor emeritus and former chapel dean, hopes is never forgotten when historical accounts of Swasey are written.

Jackson arrived on campus in 1974, a decade after the university began its secular transition, disavowing itself of any religious denomination. He’s heartened by the fact Denison, unlike some colleges, still has a separate religion department. Jackson also understands the shifting mores of the nation.

“It was a change in the culture in American society and Western society, where religion became increasingly marginalized,” Jackson said. “I think student interest in the study of religion is still strong, but student interest in public worship has waned.”

The Gilpatrick House, a short stroll down Chapel Walk, is now the center for spiritual life on campus.

Jackson remains proud of the work he, Woodyard, and others have done to promote religion and inclusivity on campus. Few are aware of the “office of human sexuality” that was run by students in the chapel’s basement in the 1970s. Overseen by Jackson and Woodyard, it was an outlet for the LGBTQ+ community and women dealing with issues they were uncomfortable addressing elsewhere.

“Students could come and speak frankly and get advice from their peers, and sometimes those peers would refer them to professional counselors,” Jackson recalled. “These may have been mainstream concerns, but they were taboo topics to talk about in certain spaces.”

Adapting to the times, chapel activities have expanded to become more secular and include a variety of artistic and academic series that afford students the chance to engage in the arts and sciences through lectures, performances, exhibitions, and academic programming. The long-running Vail Series alone has brought Itzhak Perlman, Yo-Yo Ma, Dizzy Gillespie, and Maya Angelou to the Swasey stage.

“When artists come and they see the grandeur of the chapel, they really appreciate the space and the setting,” said music professor Ching-chu Hu, director of the Vail Series. “It also serves as the public performance space for several of our larger ensembles as well as our festivals. So many in the community know Denison primarily from their attendance to these events.”

Nowadays, memories made at Denison often start in Swasey.

First-year students begin their academic voyage by assembling in the sanctuary before heading down Chapel Walk for their class induction. Over four years, the Swasey bells provide the soundtrack to campus life and the Swasey steeple serves as a lodestar for students returning home to The Hill.

“It’s the focal point of campus even though it’s been reassigned to work in different ways,” Porcheddu-Engel said. “Swasey still has the power to bring us together.”