A 15-foot-tall amalgamation of geometric curves and arcs rendered in steel, Path by Alexander Liberman was missing from campus for more than a year as Denison Museum director Megan Hancock led its conservation. Freshly buffed and shined to reclaim its former glory, Path has just returned to campus, and the timing couldn’t be better.

Reunion is just around the corner. Fifty years after Path was installed during the fall of their senior year, members of the Class of 1974 will be on campus once again. Hancock says this is particularly fitting. “This class was the first to have Path as part of their history,” she says.

Path’s own journey to The Hill is a particularly Denison story, based on liberal arts ideals and relationships. It begins with Denison trustee Edmund G. Burke.

Edmund G. Burke: Newsboy turned realtor

Burke — an “ex-realty man, developer of subdivisions” in New York City and Long Island, according to his New York Times obituary — hailed from Bethel, Ohio, a small village just outside Cincinnati. The same obituary outlined his beginnings as a newsboy whose father operated a tannery with Ulysses S. Grant.

Burke and his brother Charles departed Bethel to join a real estate firm in Pittsburgh, eventually relocating to New York to establish their own successful business. Among their acquisitions was the Long Island estate of William Vanderbilt, which they developed for a lucrative housing market. In addition to selling real estate, Burke became an avid art collector, perhaps spurred by selling the contents of Idle Hour, Vanderbilt’s 110-room mansion.

To that end, in 1943, just a year after he joined the board of trustees, he proposed Denison establish an art treasures collection, to which he donated several pieces. “Art is an integral and essential part of a liberal arts education,” he said. Students “ought to be in day-to-day contact with the best expressions of art which can be provided.”

Hancock says that collection was the cornerstone of the museum’s collection, which today numbers more than 9,000 objects.

When Burke died in 1966, his estate made a $1.25 million gift to Denison — at the time the largest in the college’s history — to build the Burke Hall of Music and Art. President Joel Smith advocated for an arts building that was itself a work of art.

The result is Burke Hall, its dramatic chalk-white walls and steeply pitched profile nestled amid Granville’s quaint tree-lined streets. Burke Hall’s modernist structure houses the museum and has provided the primary spaces for student music, art, and theatre performances for more than 45 years.

The Michael D. Eisner Center for the Performing Arts, which opened in 2019, enfolded those angles into its own architecture. Burke’s geometric spaces still echo with student performances today.

Path’s journey to The Hill

Steve Rosen, then an assistant professor of art and the first curator of the Denison Museum, recalls the story of how the Liberman sculpture came to The Hill.

“As the Burke building was going up, I had an occasion to talk with Joel Smith about the possibility of acquiring a dedicatory work of art,” Rosen wrote in a letter to his former student Jamie Hale ’78.

With a $20,000 budget — about $145,000 in today’s dollars — and the idea of something that would distinguish and contrast with the lines and color of the new Burke Hall, Rosen set his sights on New York’s famed Andre Emmerich Gallery.

Liberman, whose work had been collected by several museums, was a contender. The gallery director arranged for Smith and Rosen to meet Liberman at his studio in Warren, Connecticut. Rosen detailed the brunch they enjoyed.

“We arrived at 11:30, chatted with everyone for a while, and then sat down for a splendid meal of cured ham, fresh spring corn, Boston lettuce, and dessert,” Rosen wrote. “Smith sat with Liberman and his daughter, Francine du Plessix Gray, an early feminist writer married to Cleve Gray, a painter. I was seated with Mrs. Liberman and Mrs. Horowitz, (daughter of conductor Arturo Toscanini) and spouse to (legendary pianist) Vladimir Horowitz, who, according to Mrs. Horowitz, was at home listening to his own recordings.”

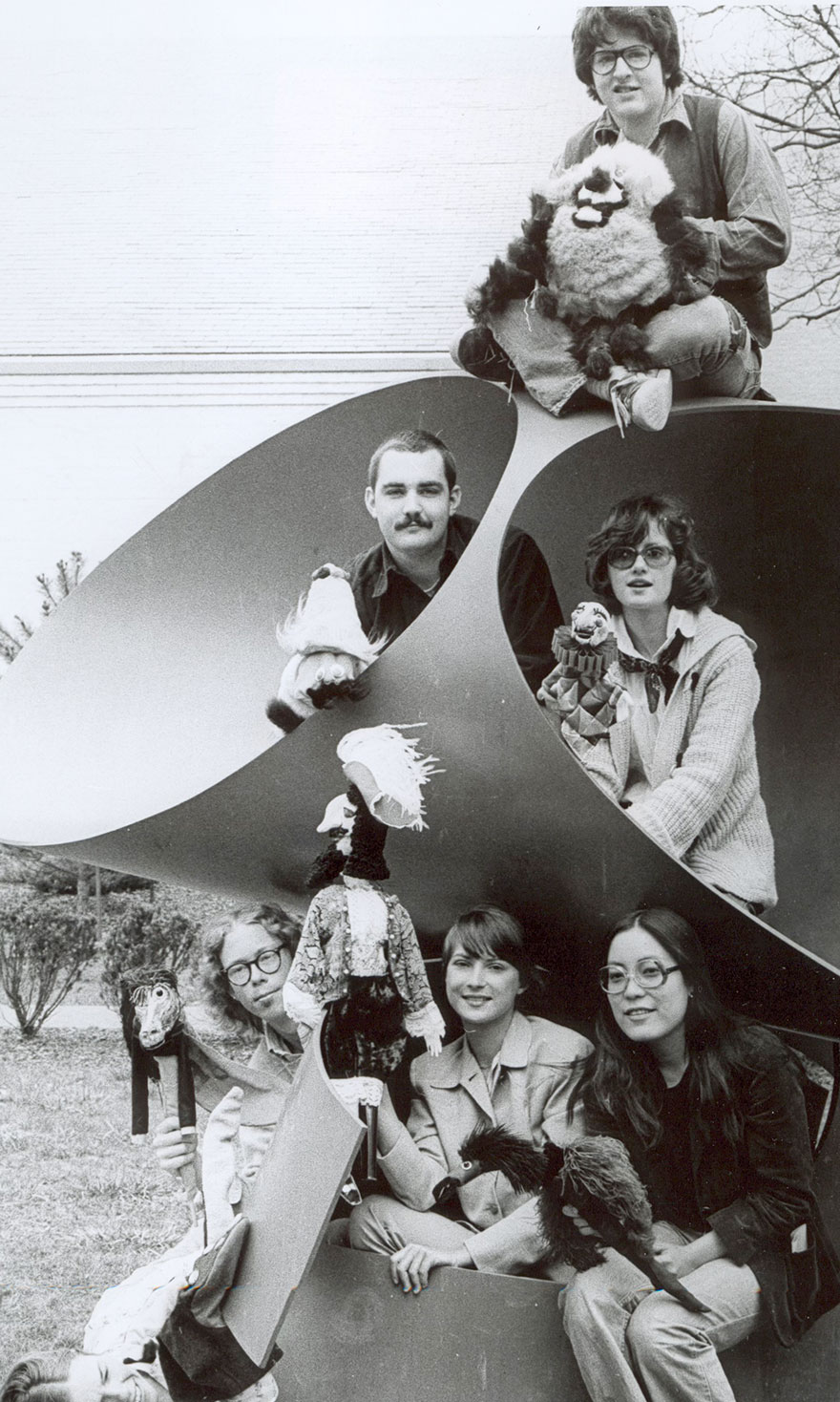

Plans solidified for Path to find a new home on The Hill. Its red, curvilinear forms set off Burke Hall’s pure white angles admirably. Originally installed between Burke and Broadway to early criticism in the village — from whom Rosen heard Path was “junk, wrong color, doesn’t mean anything” — as time passed, Denison students and Granville schoolchildren alike clambered over the structure, claiming it for their own. The sculpture’s location facilitated adoption as a local landmark, as in: “Turn left at the orange cannoli.”

Although the steel construction weathered central Ohio storms and student hijinks, Path began to fade and rust. In 2009, it was disassembled and sent off for reconditioning. Repositioned in a new home, Path now glowed against the west wall of Burke. But something wasn’t quite right. Path’s refreshed color wasn’t exactly its original hue.

A conservator was engaged to bring Path back to life, and Hancock partnered with the Liberman Foundation to source the signature “Liberman Red,” similar to the warm, vibrant red of a poppy.

“While we are men and women of the present, we must not neglect our past,” President Smith said at the dedication of Burke Hall and Path. On June 1, 2024, as the Class of 1974 gathers at the museum for an alumni art show, Path will be radiant once more — linking the past to the present, and marking a path to the future.