On a morning stroll across campus, biology professor Warren Hauk pauses in front of Slayter Hall to smell the Itea virginica.

Professor Warren Hauk holds one of the many pairs of tinted glasses that he must keep close at hand to combat headache-inducing bright lights and sunshine. His first line of defense is darkly shaded non-corrective contact lenses.

Anyone can sniff roses, but Hauk, a man devoted to the study of plants, wants all of us to broaden our horticultural horizons.

“Don’t ask me the common name of Itea virginica,” he says. “My brain, for whatever reason, can hold either the Latin name or the common name, but not both.”

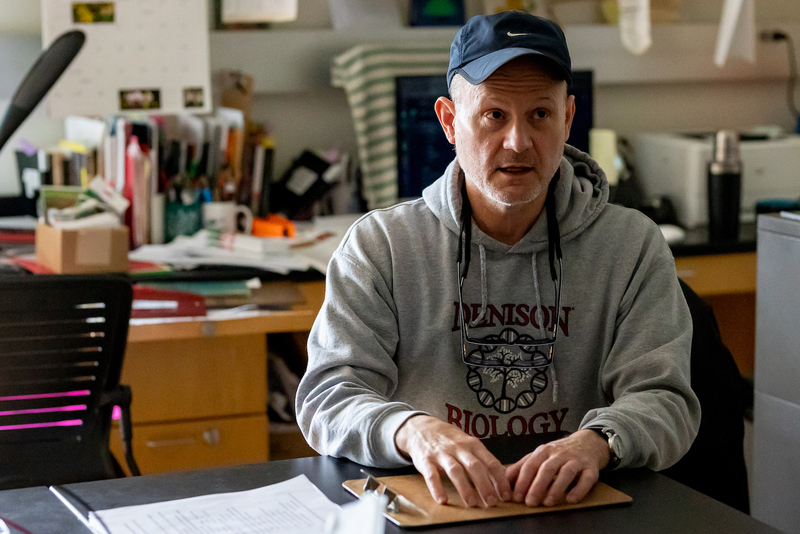

The bespectacled educator is wearing a black cap, a gray Denison Biology hoodie and his trademark fanny pack. His most intriguing accessories, however, are the three pairs of shaded glasses dangling from his neck.

As the sky brightens, Hauk reflexively reaches for his prescription sunglasses with the flip-down polarized clip. Days like these, where the sun plays peekaboo among the clouds, are troublesome for people with his condition.

Hauk searches his cellphone for the common name of the flowering shrub — it’s Virginia sweetspire! — and keeps walking toward a place of great inspiration. Halfway down Presidential Drive, he stops along the sidewalk and calls attention to an in-ground limestone tablet bearing an inscription from French novelist Marcel Proust.

The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.

Hauk recites the quote to students in his Plant Systematics course. The message: Train your powers of observation to appreciate and identify all the beauties of nature.

Since a life-altering trauma in 2018, the passage has taken on deeper meaning. That’s the year Hauk became hypersensitive to light, triggering debilitating headaches.

A professor who loves to work outdoors suddenly could only do so during certain hours of the day. His world was plunged into darkness, every aspect of life dependent on his ability to control the environment of light.

It’s only because of his unwavering love for teaching, the understanding of his students, and the support of Denison faculty that he’s celebrating his 25th year on campus.

“So many doors have closed because of this,” Hauk says. “But others have opened, allowing me to see the world with new eyes.”

“Begin building a new set of dreams”

The sticky note outside his sixth-floor Talbot Hall lab reads:

Please knock on the door! I keep my lights turned off almost all the time — Dr. Hauk.

The shades are drawn. The frame of the desktop computer is blanketed to cover flickering light. The computer screen is tinted. It takes a visitor a few moments to locate the silhouette of Hauk hunched over a keyboard, researching the DNA of ferns.

“Being a biologist who’s not able to work outdoors on sunny days is a special kind of torture,” says Hauk, who also teaches Queer Studies courses.

Hauk knew he wanted to pursue biology in grade school, immersing himself in the majesty of his family’s gardens and farms. He was living his dream until 2011 when a pair of car accidents five months apart left him with post-concussion syndrome.

Over the next seven years, he endured occasional bouts of mild light sensitivity, but none of it prepared him for what happened next. A routine eye exam in which his pupils were dilated sparked “an explosion” later diagnosed as photophobia.

“It became almost a full-on intolerance to most light,” he recalls. “It was like my brain was unable to regulate its reaction to light and it caused inflammation leading to headaches.”

Visits to doctors across the medical spectrum produced few answers and little hope of regaining normal vision.

Hauk fought through the pain to keep teaching in the spring of 2018. He wore sunglasses in the classroom and his students were kind enough to not make an issue of a professor who clearly was struggling with his environment.

He spent his time away from Denison confined to dark rooms. His partner, Vasko, began the task of driving him to campus, which continues to this day. Hauk required a mask and a wheelchair to negotiate airports, the fluorescent lights wreaking havoc on his nervous system.

“There’s all this bargaining you go through because you don’t want to lose hope of getting back what you’ve lost,” he says. “Mercifully, there’s a gradual awareness that, ‘It’s never going to be the same again.’ You can be bitter and angry at the injustice, or you can just face reality and begin building a new set of dreams.”

Building critical-thinking skills

Hauk tells students there are 280,000 species of flowering plants. Charlie Smith ’23 once embodied a different species in the classroom — a wallflower.

That all changed when Smith took his first of three courses with Hauk.

“I didn’t talk much in other classes,” Smith says. “But in Dr. Hauk’s classes, I talked all the time. I love his teaching style; it’s very engaging. I had to resist the temptation to put my hand up every time.”

Hauk doesn’t like to lecture. He’s not one to demand his students simply memorize all the plants and their life cycles. The professor promotes discussion and builds the fundamental skills of thinking critically.

He lives by the words of forestry engineer Baba Dioum: We conserve only what we love; we love only what we understand; and we understand only what we are taught.

“I enjoy Dr. Hauk as a professor,” says Courtney Fouke ’23. “I need a positive environment to learn, and that’s what he provides.” At the beginning of each semester, Hauk shares his story with students. He explains what happened to him five years ago, and why he won’t be able to accompany them into the greenhouse and the community garden on sunny days. His knowledge of his subjects and his ability to teach them are such that his students don’t mind they are learning in one of the most dimly lit labs on campus.

Professor Warren Hauk touches the limestone tablet with an inspirational inscription from French novelist Marcel Proust. It reads: “The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeking new landscapes, but in having new eyes.”

Sweet dreams

Hauk lauds the kindness and humanity of Denison faculty and administrators. Without their understanding, he might have retired several years ago. His willingness to persevere also was aided by a conversation with a campus electrician. After learning of Hauk’s challenges, the staff member volunteered to replace the headache-inducing fluorescent bulbs in his lab with LED lighting. He then wired each light fixture to ensure only the middle bulbs illuminated when switched on. The light fixtures under which he teaches remain off and the window shades stay drawn.

It was a game changer for a professor who wears tinted non-corrective contact lenses and treats inflammation caused by unexpected invasions of light with steroids.

“When we have staff meetings, someone will always get up and make sure the shades are down when Warren enters a room,” says Ayana Hinton, associate provost for diversity, equity and inclusion. “He can’t participate in as many workshops and committee meetings as he once did, but it’s inspiring to still see him doing what he loves. He never gets down or has a pity party.”

Hauk lives a fulfilling life. He’s taken up yoga, introduced a Science of Gardening class for non-biology majors, and dedicated more time to scholarly research.

His happiest hours are spent in his backyard tending to his gardens early in the morning and at dusk and playing with his three dogs. It reminds him of his idyllic childhood growing up in Missouri.

As he harvests garlic plants from a garden, Hauk is asked if he ever wakes from a dream in which he still walks through life bathed in sunshine.

“Nah, I dream of still having hair,” Hauk says, removing his cap to reveal a balding head. “I was never the guy who likes spending time at the beach, anyway.”