A medieval manuscript providing a medicinal road map for outliving an apocalypse resides in the Special Collections section of Denison’s Doane Library.

It’s 563 years old and looks quite fetching for its age.

Impeccably handwritten by a teenage German scribe in the 15th century, the manuscript has survived wars, plagues, time, and indifference. It sat in a desk drawer for at least a year after being donated to the university in 2003.

The manuscript’s rich and colorful history — it features the treatise of a radical 14th century alchemist confined to a papal dungeon — might have remained obscure had it not come to the attention of a Denison English professor, a self-described “picker-up of unconsidered trifles.”

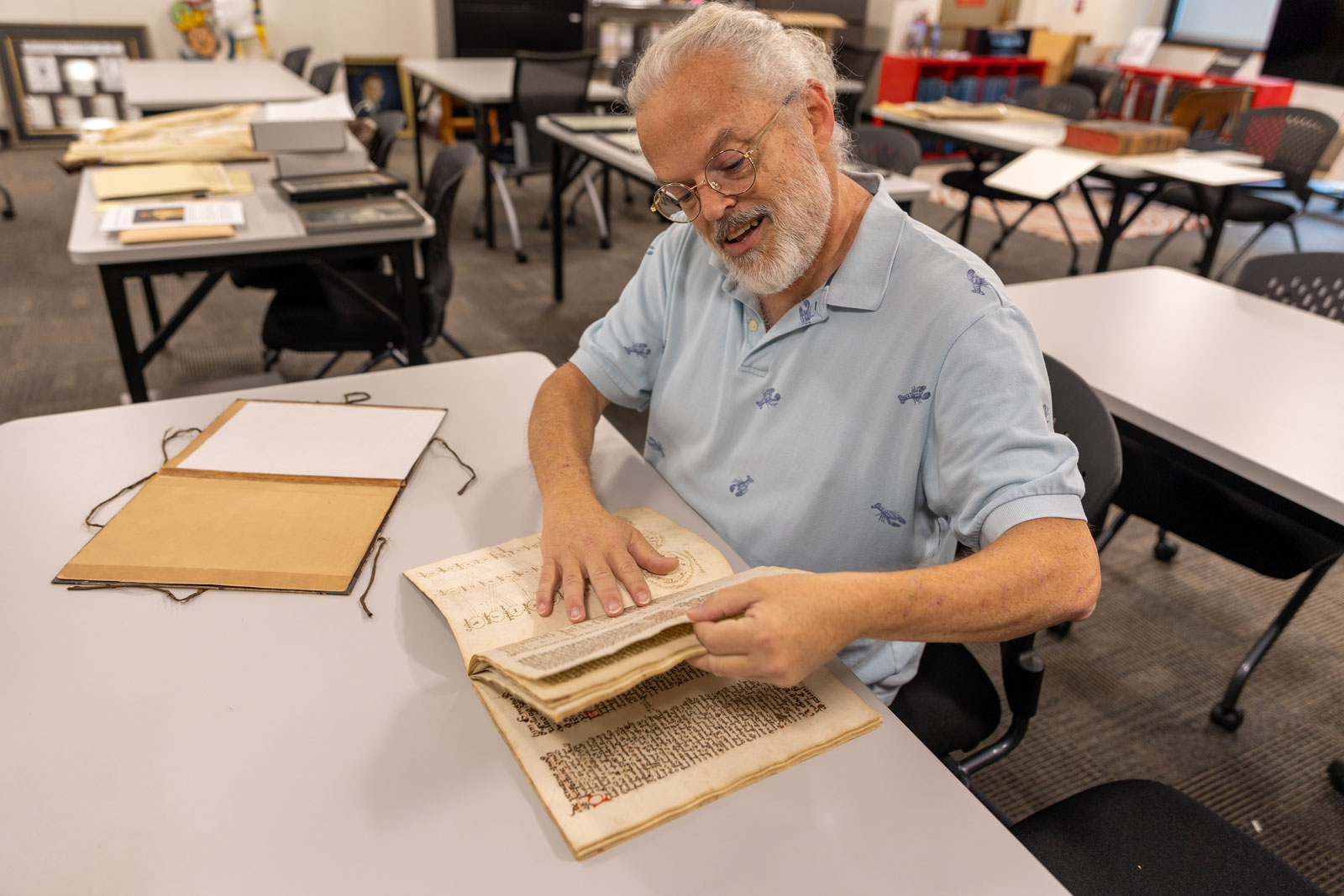

When Fred Porcheddu-Engel ’87 learned of its existence in 2005, he couldn’t believe the good fortune bequeathed his alma mater.

“It was totally an Indiana Jones moment,” says Porcheddu-Engel, who once wrote an essay on an obscure English poet after finding his notebooks, incorrectly cataloged, in a Cambridge, England, library. “What do you do when you discover that a remarkable treasure is located right in your midst? What you do is spend years of your life squeezing it like a sponge.”

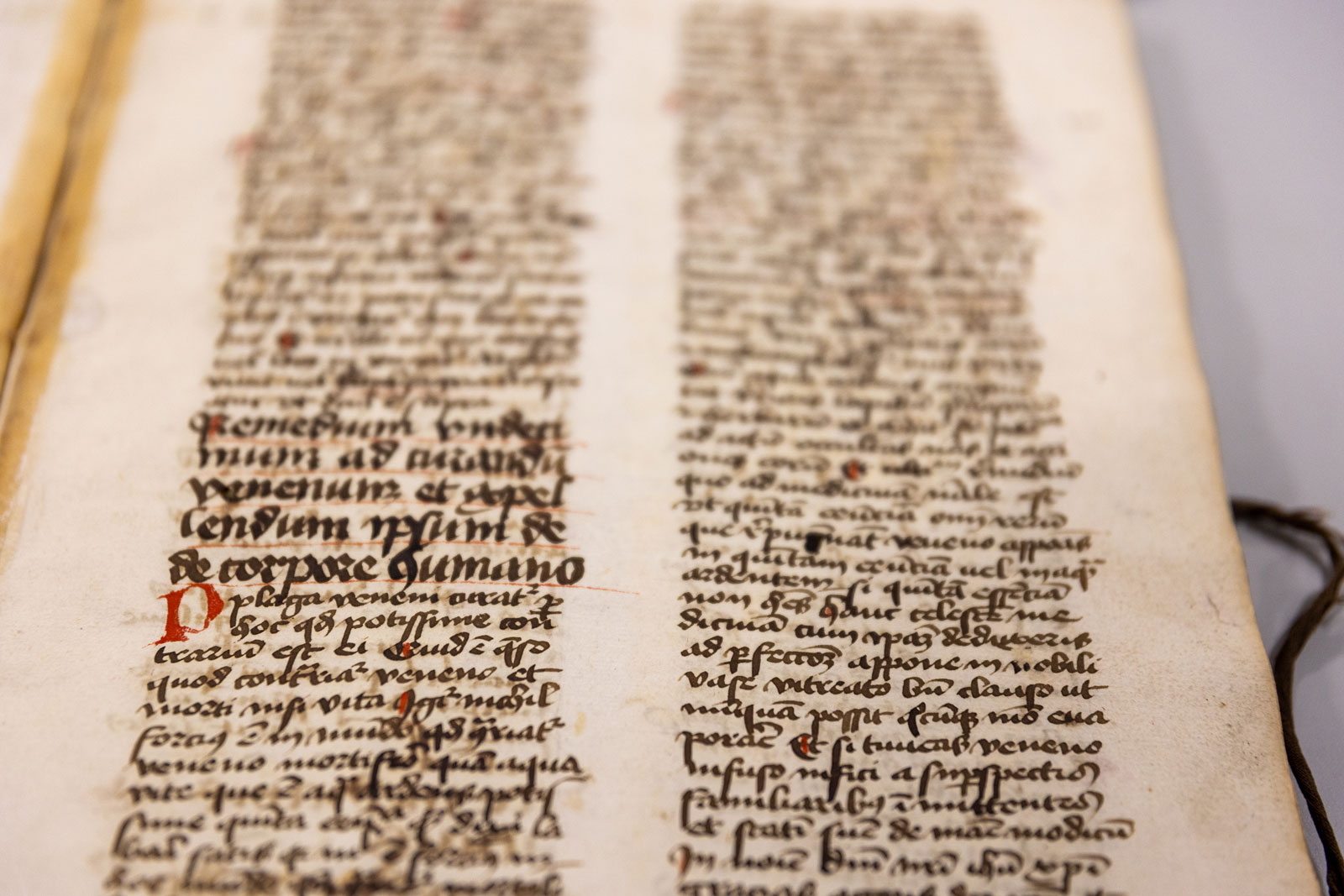

Fully intact medieval manuscripts are rare possessions for small colleges. Here was one of the first examples of medical chemistry, explaining the human benefits of distilled ethyl alcohol, just waiting to be transcribed from Latin to English.

Modernizing medieval studies

Nearly two decades of research, including multiple trips to European libraries to photograph other existing copies, are coming to fruition in the form of a website showcasing the educational perks of owning a unique artifact.

In 2022, Porcheddu-Engel received the R.C. Good Faculty Fellowship, which grants tenured faculty a semester-long release from teaching and advising to complete a major research project.

Best known for his engaging approach to English literature and medieval studies, Porcheddu-Engel dedicated the fall of 2022 to building the website. Once complete, it will catalog the approximately 250 known copies of the treatise, digitize and translate each page of Denison’s version, promote discussion of medieval topics, and include video of Denison chemistry professors and students conducting experiments to test the assertions and remedies of 14th century French alchemist John of Rupescissa.

Like many texts of its era, the manuscript was penned on highly durable parchment made of animal hide.

Celebrating his 30th year of teaching at Denison, Porcheddu-Engel continues to step outside his comfort zone, bringing medieval times into the digital age with hopes of attracting larger and younger audiences. He’s also paying tribute to the university’s long tradition of alumni donations to the library’s Special Collections.

The manuscript — its 120 pages are about as thick as a thumb — was among the literary gifts given to Denison by Elizabeth D. Sturges ’54.

“We can’t own hundreds of these coffee table manuscripts the way they can at Harvard and Yale and universities in Europe,” he says. “But the things that are given to us through the generosity of the alumni or the friends of Denison, we need to take them seriously and say, ‘This is worth our study.’”

Students join Porcheddu-Engel’s quest

Bridget Koerwitz-Crosley ’21 was recently married, and her ring offers a clue to one of her great passions. The blue stone, lapis lazuli, was once ground up and used as ink by scribes to write and decorate medieval texts.

“I was always drawn to the beautiful handwriting,” Koerwitz-Crosley says. “I did my senior thesis on manuscripts.”

She found a kindred spirit in the colorful Porcheddu-Engel, who ambles across campus in the summer wearing bright blue shirts emblazoned with kiwi and socks with shellfish. The professor fed Koerwitz-Crosley’s curiosity about the Middle Ages and recruited her to assist him in the manuscript project.

1. The engagement ring of Bridget Koerwitz-Crosley ’21 is made of lapis lapis, a blue stone once ground up and used as ink to write and decorate medieval texts.

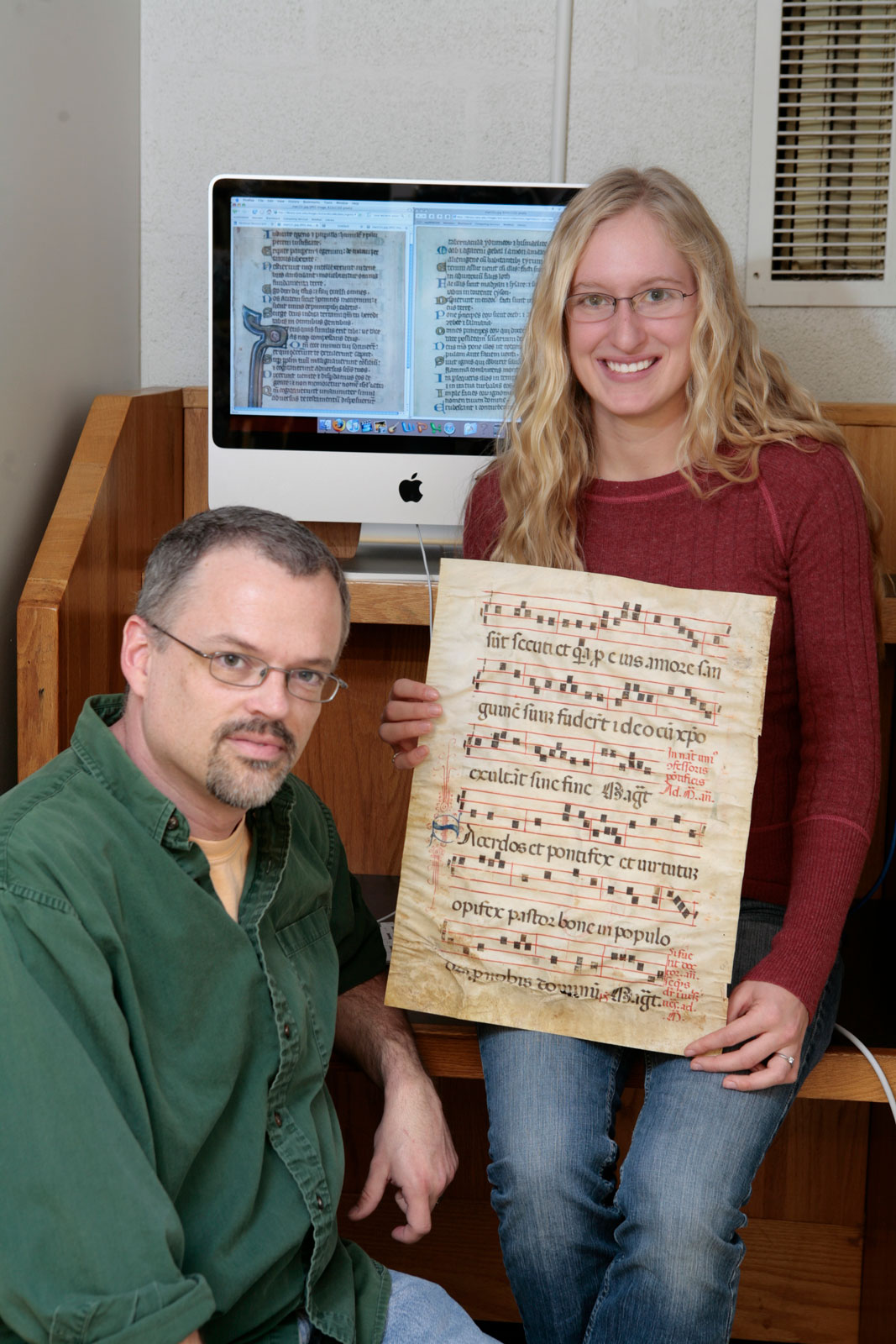

2. Greta Smith ’08 helped Porcheddu-Engel launch Denison’s inaugural digital humanities project in 2007.

Koerwitz-Crosley and Jordan Cardinale ’20 joined Porcheddu-Engel at workshops and helped him assemble the skeleton frame of the website during their time at college. The professor and two Denison graduates co-authored an academic essay, “Midwestern Alchemy: The Global Context of a Small-Town Manuscript.”

“I’ve discovered so many interests I didn’t know I had working with Fred,” Cardinale says. “I’m pretty sure I became an English teacher because of him.”

Pioneering spirit

Porcheddu-Engel, who considers himself a “book nerd,” was overjoyed to peruse the material gifted by Sturges, whose grandfather purchased it in Heidelberg, Germany, in 1877. The manuscript is one of Denison’s oldest texts. Like many texts of its era, it was penned on highly durable parchment made of animal hide, which ages more gracefully than common paper.

As the digital age dawned, Porcheddu-Engel recognized the sea change in his field. Everything was going to the internet, and he needed to embrace technological advancement to reach students and “citizen humanists,” ones who might have an interest in the topic but lacked the time to spend traveling to libraries containing the ancient texts.

“The tempo, the pace of scholarship, even in something like medieval studies, which had been glacial in the past, has really sped up because so many things are online now,” he says.

Porcheddu-Engel and Greta Smith ’08 founded the university’s inaugural digital humanities project in 2007. It involved photographing individual pages of religious text from Denison’s collection and traveling around Ohio to locate pages from the same book. The professor believes it was the first such digital endeavor dedicated to medieval writings, paving the way for the research of Cardinale and Koerwitz-Crosley.

“His enthusiasm is contagious,” says Smith, now an English teacher. “I try to bring the same high-energy approach to my students.”

Who was John of Rupescissa?

Porcheddu-Engel spent two years translating the bulk of the manuscript. What he discovered, to his delight, was that the treaties’ central author was a James Dean for the Middle Ages.

John of Rupescissa, also known as Jean de Roquetaillade, Fwas a rebellious Franciscan alchemist who rattled ecclesiastic cages. His prophecies and antagonistic attitude toward church leaders frequently landed him in jail.

“He was a troublemaker who believed the church should be poor and not own property,” the professor says. “He wrote a tremendous amount of stuff in prison, where he clearly got access to books and writing paper.”

Since the transcript’s arrival at Denison, Rupescissa’s reputation as a “lunatic Franciscan friar” has undergone a transformation. Some modern scholars now see validity in the work with ethyl alcohol and herbal remedies.

“He’s the first person in Europe who’s known to have connected the distillation of alcohol with something other than just getting drunk,” Porcheddu-Engel says. “Our manuscript is a survivalist’s text written by a guy who thought the prophecies in the Book of Revelations were about to come true.”

The office of Fred Porcheddu-Engel is filled with books, toys, and trinkets given to him by students over the past 30 years.

The manuscript project requires the professor to be part scholar, part detective, part linguist. When Porcheddu-Engel began his work, there were 150 known copies penned by various Europeans. In recent years, he’s located another 100 copies online, using his rudimentary understanding of about 15 languages to decode their details.

The various manuscripts have different interpretations depending on the scribe. It illustrates the “power of the pen” — or quill — in understanding historical figures and events. How a medieval author characterizes a topic can have a profound impact in how we view it today.

The Denison manuscript was written by “Reymbertus Eynbeck,” who signs and dates it four times. He completed the work, which features two other minor alchemical texts, early in 1459.

What happened next is an historical mystery.

Nothing is known about the manuscript until its purchase by Sturges’ grandfather in the 19th century. But unlike so many other valuable works from the Middle Ages, it wasn’t destroyed, defaced or disassembled. Controversial 20th century book collector Otto Ege removed thousands of pages from his manuscripts and either sold or gave them away to smaller institutions such as Denison so they could own a piece of history.

Adding to the manuscript’s rarity is the topic. It’s not religious or literary in nature, but a work of science. Porcheddu-Engel wants his project to involve multiple disciplines, so he’s drawing on support from the data analytics and scientific communities to complete the website.

“One of the best things you can do at a liberal arts college is treat it like a liberal arts object,” the professor says. “Let’s explore it from every angle.”

Once the website goes live in the spring, it will ensure the manuscript’s eternal life — a survivalist guide in the spirit of John of Rupescissa.

“I want people to see that it’s possible to participate in a digital network of information using old objects that still have plenty to teach us,” Porcheddu-Engel says. “They teach us about our relationship to science, our relationship to religion, our relationship to the past.”