So much of the athletic director’s life is here, packed within these four walls.

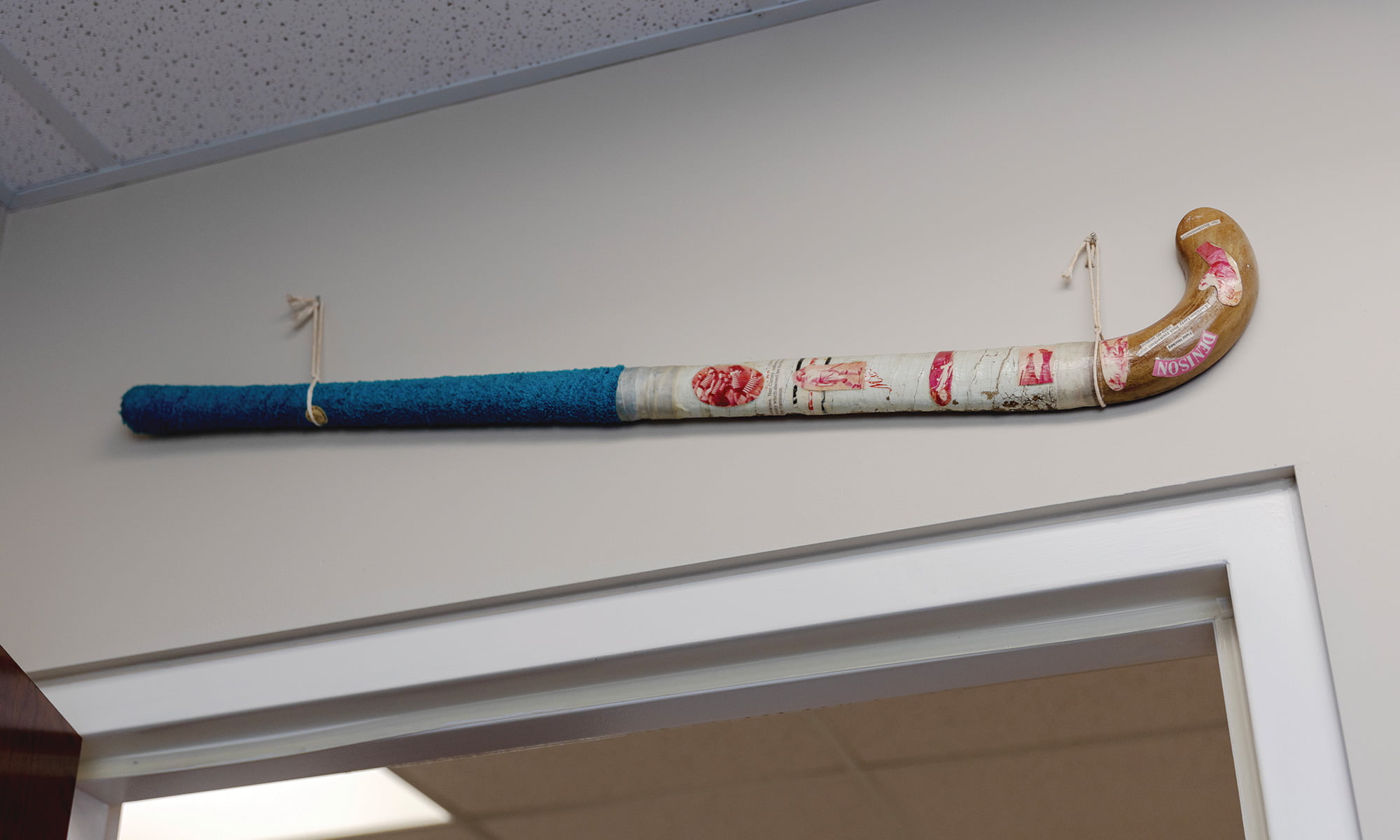

There’s the 40-year-old field hockey stick hanging over her doorway. 1 The photograph of her family in the bleachers after a field hockey game — parents clad in plaid, fresh off a round at the Denison Golf Club, older sister sprouting a pair of bunny ears behind Carney-DeBord’s head. 2

There’s the line of bright yellow rubber ducks on her window sill. The keys to a long-gone desk. The magnet affixed to her file cabinet: “Well behaved women rarely make history.” 3

It’s an evolving collection. Carney-DeBord’s story is still unfolding.

In some ways it began here at Denison, in 1976, when the local athlete matriculated at the college atop the hill intent on becoming a dentist. She loaded up on tough science classes and lettered all four years in basketball and field hockey and along the way met “someone really special who saw in me what I didn’t see in myself.”

Jack was a fellow athlete who wanted to coach, and he thought Carney-DeBord could lead a team as well. He encouraged her to balance those challenging science courses with an easy January term credit by coaching basketball at the local high school.

“And then January was over and they asked me to stay,” Carney-DeBord says. “I went to classes all day and coached in the evenings. I fell in love with coaching.”

And Jack? He captured her heart, too. “There was nothing else to do but marry him,” she says. (That photo over by the door is Sebago Lake in Maine, where they exchanged vows and baptized both of their boys.)

Carney-DeBord had her mind set on coaching a college team, and though she heeded her advisor’s advice to devise a backup plan — invaluable wisdom, it turned out, that opened her to the social sciences — she ultimately didn’t need it. At age 23, she was hired on as the head field hockey coach at Bethany College in West Virginia, an opportunity she almost immediately blew by losing her first contest 10-0.

“Which is, yeah, bad,” she says. She was a nervous wreck facing the athletic director who’d taken a chance on her. “I was like, OK, well he’s going to regret this decision of hiring me. But he just said, ‘The good news is the next team on your schedule is in conference, so it should be a much more competitive game. Glad you had a safe trip.’”

That conversation — and the man delivering the message — set the standard for the kind of leader Carney-DeBord wanted to be. David Hutter, who later became athletic director at Case Western Reserve University, remained her mentor for decades. (That’s his picture up there on the shelf.)

Mentors have always been important to Carney-DeBord. When early in her career, she had to choose between a position at Denison and rival Ohio Wesleyan University, another mentor — longtime OWU coach and athletic director Richard Gordin — encouraged her to opt for the latter.

“You don’t want to go back to your alma mater,” he said, “because they’ll still see you as a student.” Hutter suggested she pursue basketball, a gender neutral sport, over field hockey, which would provide a strong leadership foundation for a long-term goal of becoming an athletic director. At Ohio Wesleyan, Carney-DeBord went on to become a tenured faculty member, full professor, and one of the winningest coaches in Division III women’s basketball history, guiding OWU to six NCAA Division III Tournament berths.

“Flash forward 25 years when I was offered this position (as athletic director at Denison),” Carney-DeBord says, “and I took (Gordin) out for coffee and said, ‘Is it OK now? They’ve probably completely forgotten me.’ “He said, ‘Yeah, OK, it’s a good decision.’”

Carney-DeBord returned to The Hill in 2011, encouraged by Denison’s trajectory. When Adam Weinberg, a former college hockey player, was selected as the university’s 20th president two years later, “I just felt my stars were aligned,” Carney-DeBord says. “He really understands how athletics aligns with the liberal arts and enhances the academic experience.”

The decade since has been a rewarding one. Since Carney-DeBord’s return, Denison has won 50 North Coast Athletic Conference Championships and four Division III national championships, and the college has completed $38 million in renovations and expansion to the Mitchell Center. 4

In 2019, she was named the Under Armour Division III Athletics Director of the Year by the National Collegiate Directors of Athletics, and in 2021 she was the NCAA Division III Women Leaders in College Sports Nike Executive of the Year.

(That award is here too, and it’s Senior Associate Athletic Director Sara Lee’s favorite item in her boss’s office: “This has special meaning to me,” Lee says, “as I have attended this organization’s national conference with her the last several years and feel she was so deserving of this honor and recognition for all she has done and continues to do to move our department and university forward.”) “Nan brings great passion and vision to the department,” says Gregg Parini, who’s turned Denison into a swimming powerhouse over his 35 years as the head men’s and women’s coach. “She’s an invested leader who cares deeply about our coaches, our staff, and our student-athletes. Her commitment to building an elite athletic experience is evident on a daily basis.”

Parini’s success is part of this office, too. His favorite piece hangs high above Carney-DeBord’s head, flanked by framed accolades — a painted window that celebrates the men’s first NCAA swimming championship in 2011. 5

In fact, the more you look around these walls and shelves, the more you realize the plaques and trinkets and baubles are less about Carney-DeBord and more about the people who surround her. There’s an old tennis racket. A football helmet. A track and field letter. The framed words of encouragement she once offered a former player. The yellowed newspaper story about the growth of the NCAC with a picture of Carney-DeBord and longtime Denison coach and administrator Lynn Schweizer, arms thrown over each other’s shoulders. 6

This is an office occupied by one person but built by a community — a space that celebrates the former colleagues and coaches who came before her, the mentors and heroes and friends, the players and parents and alumni who continue to write her story.