Part 1: Tsune Chi Yü 1921 Comes to America

In 1918, a young man made the month-long voyage from his home in China to America, crossing the Pacific by ship and the states (there were only 45 states in 1918) by rail. He carried western clothing, his high school pennant, a working knowledge of English, and the complicated history and hopes of his home country.

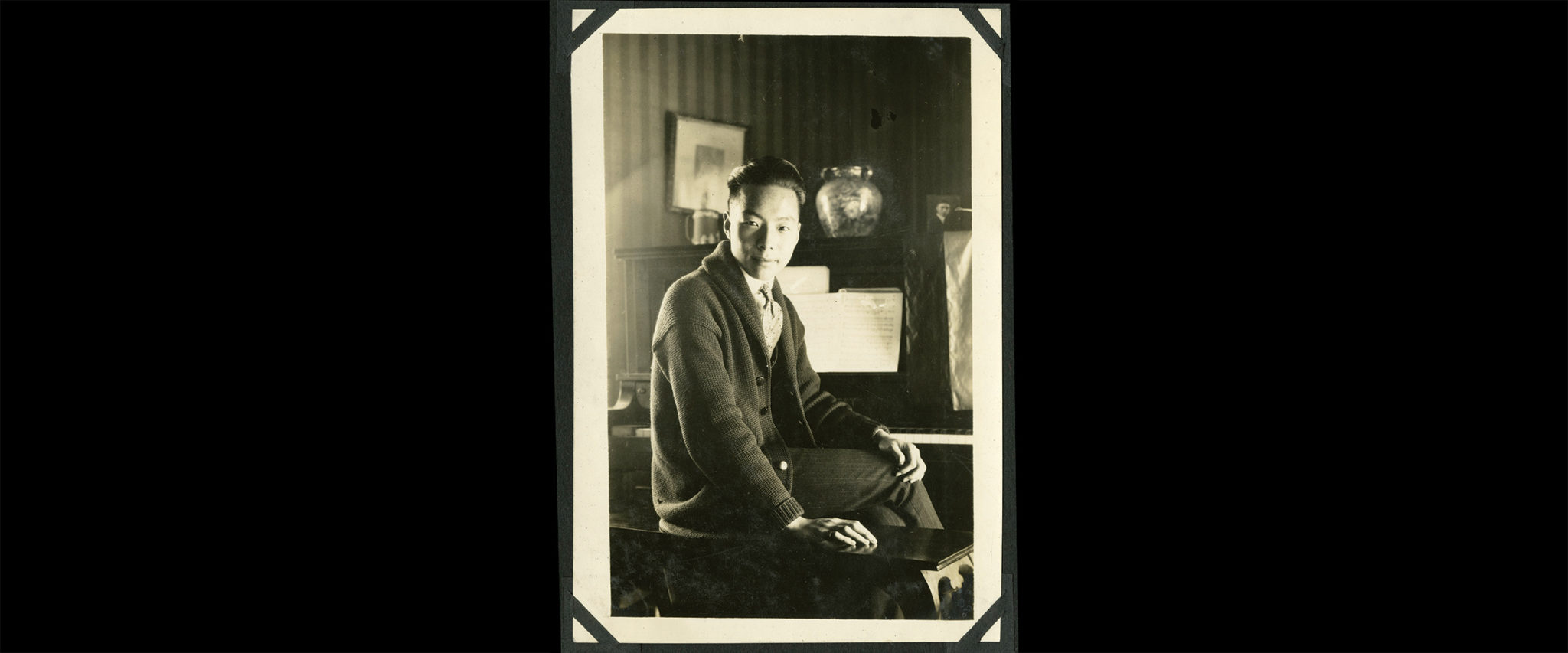

Tsune Chi Yü 1921 also carried the portable bellows camera he used to document the next four years of his life, spent in a rural Ohio village with unpaved streets, a few motorcars, and a university.

This past April, one century to the year after Tsune Chi’s journey, Denison’s library was contacted by a book distributor in Italy:

“I’m writing from Florence, Italy, for a special case that occurred to us, and we think could be interesting and curious for your library, too.”

A private library in Florence was being sold, and it included a vintage photograph album. Embossed on the fragile suede cover in gold lettering was “Tsune Chi Yü,” the name of the distinguished Chinese Ambassador to Italy who died in 1968, in Taipei, Taiwan.

Denison’s library purchased the album, and the chronicle of Tsune Chi’s undergraduate years, 1918-21, was returned to Granville after almost a century abroad. In many ways, it’s a typical amateur photo album of the era, pictures affixed to black pages with gummed corners, captioned using white ink and a fountain pen. The handwriting and brief comments reveal a character of discipline, deep feeling, and a sense of fun.

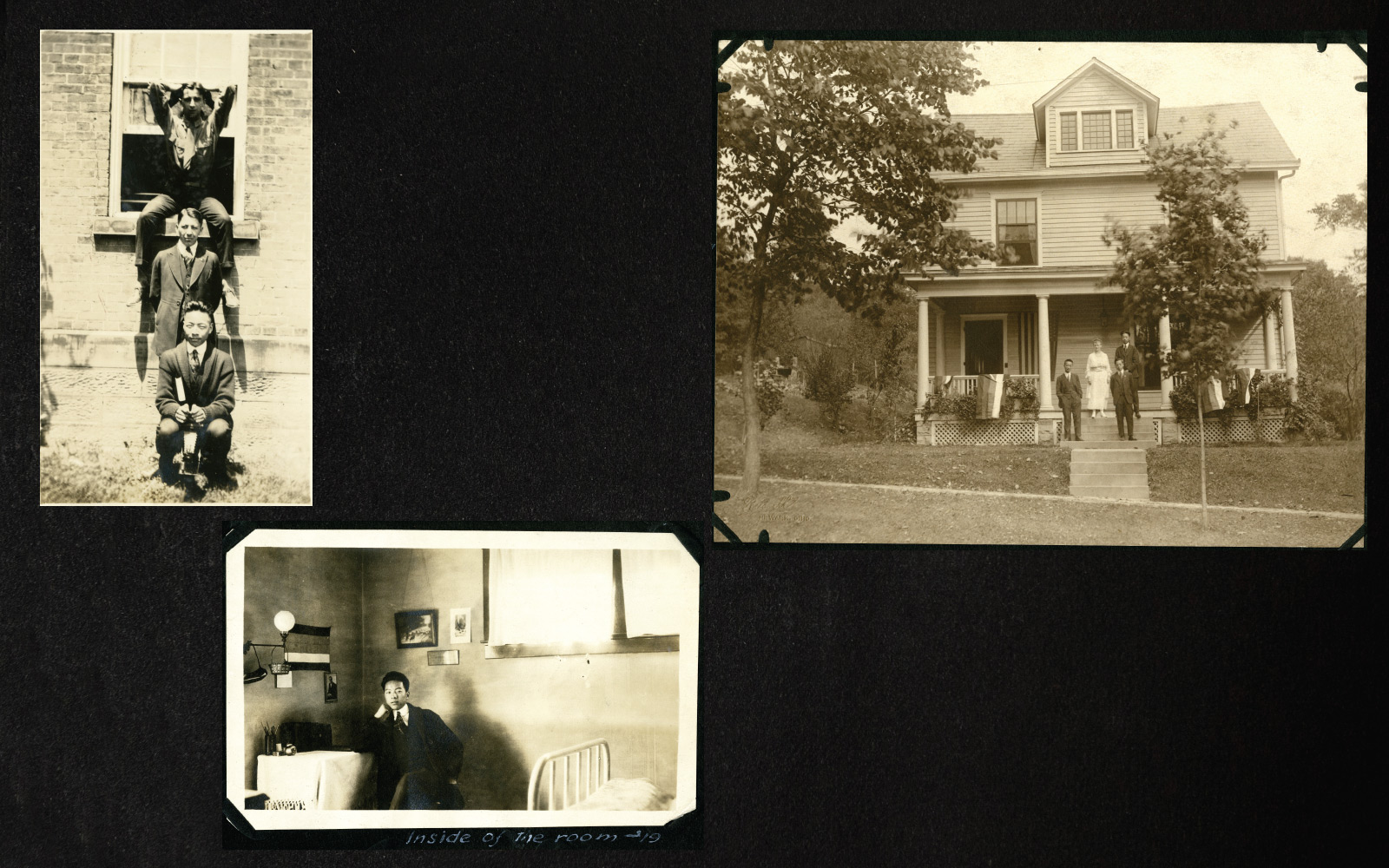

The two opening pages of the album are significant. The first honors the LaFerre family on Summit Street, specifically Miss Blanche LaFerre. The LaFerre family was Tsune Chi’s American family, and their home was his home for his undergraduate years. There are frequent pictures of him and Miss LaFerre outside the house, and at the dining room table with friends for birthdays and Christmas. He had a room of his own on the third floor of the house, where he displayed his American flag and “Nan Kai” high school banner. A cat named Jiggs was an “honored guest” who climbed the stairs to Tsune Chi’s room.

The second page of the album is a striking formal arrangement of Chinese calligraphy in white ink and brush, positioned north, south, east, and west of a portrait of Tsune Chi. It’s a declaration of principles, a statement of purpose from an educated and ambitious young man very far from home, reminding himself that his home country was the reason for this engagement with the West.

“I will focus all my mind and intention, I will cleanse my heart of all distractions to concentrate on family, clan, country, world: everything under heaven. Through this mind, through this body.”

Tsune Chi Yü was a Nationalist (Republican) and a patriot—he was taking his first steps into the world outside of his home, a country that had suffered turmoil and difficult setbacks on the world stage, but one that he had been schooled and prepared to redeem. The way forward was interaction and understanding. Diplomacy. The future greatness and reputation of his country were in his hands.

Left: Tsune Chi holds his camera between his knees while mugging with friends in a window of Marsh Hall, headquarters for the Denison Commons Club.

Middle: Tsune Chi begins his life as a student in America beneath a striped flag of the Republic, on the third floor of the LaFerre house.

Right: The LaFerre house at 230 Summit Street was Tsune Chi’s home away from home for four years in Granville. He stands on the front porch with Miss Blanche LaFerre, his host and new friend, and two other Denison students from China on the lower step. The American flag welcomes the students to their new country, and hanging from the porch railing are three early flags of the Republic of China, founded in 1912.

Left

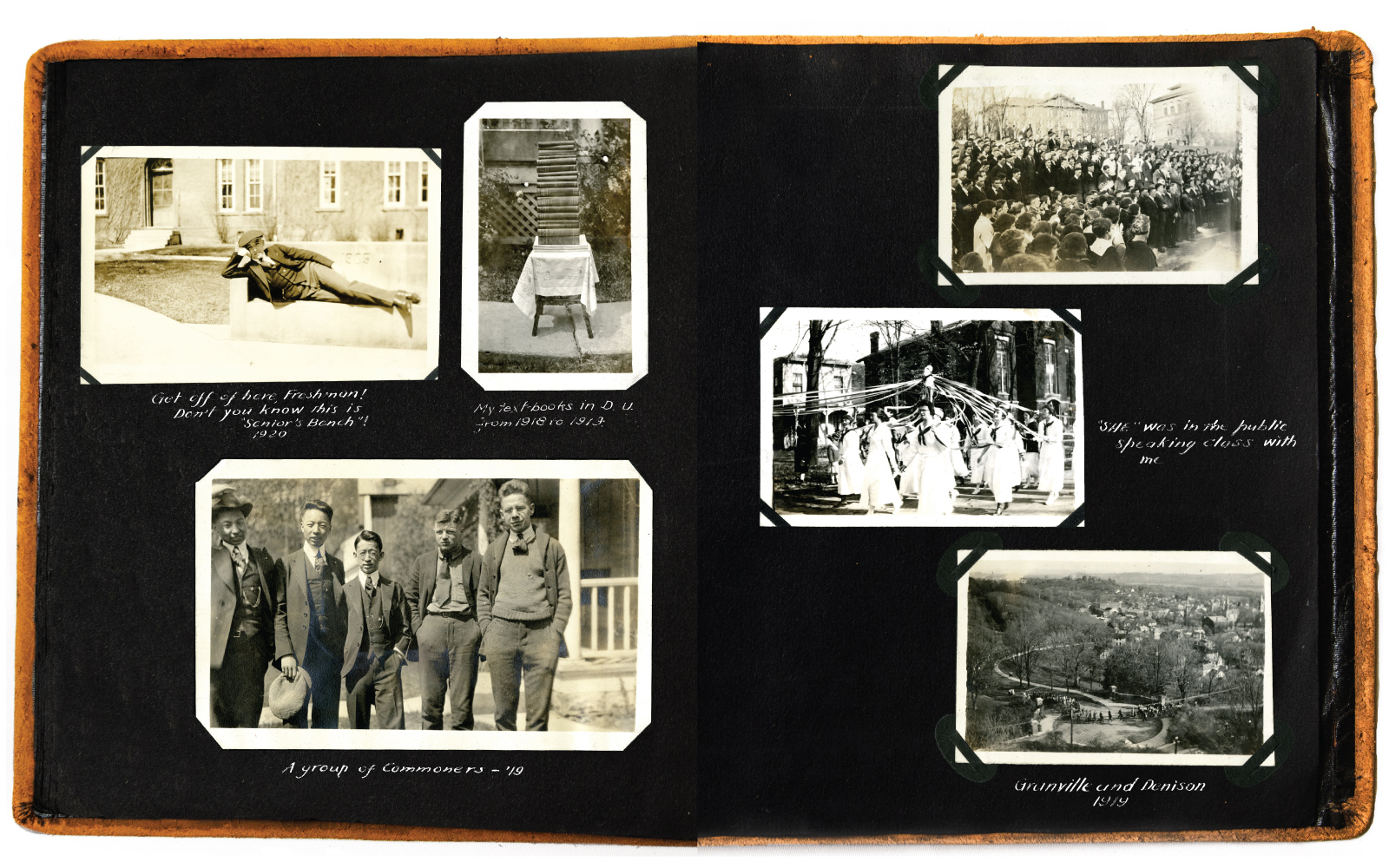

Above left:

Tsune Chi had keen instincts for the fine points of diplomacy and humor, pointing out a freshman’s audacity, sprawling on the “senior bench” in front of Talbot Hall.

Above right:

A freshman’s “Still life with text books.”

Bottom:

Tsune Chi (second from left) with some fellow “Commoners,” members of the Denison Commons Club, founded two years earlier.

Right

Top:

Denison students gather on South Plaza to mark Armistice Day, the end of World War I in Nov.ember 1918.

Middle:

The Granville parade marking the first anniversary of Armistice Day, November 1919. A young lady of interest marches past the Presbyterian church.

Bottom:

A stream of Denison students climb the Main Drive up to campus from the village.

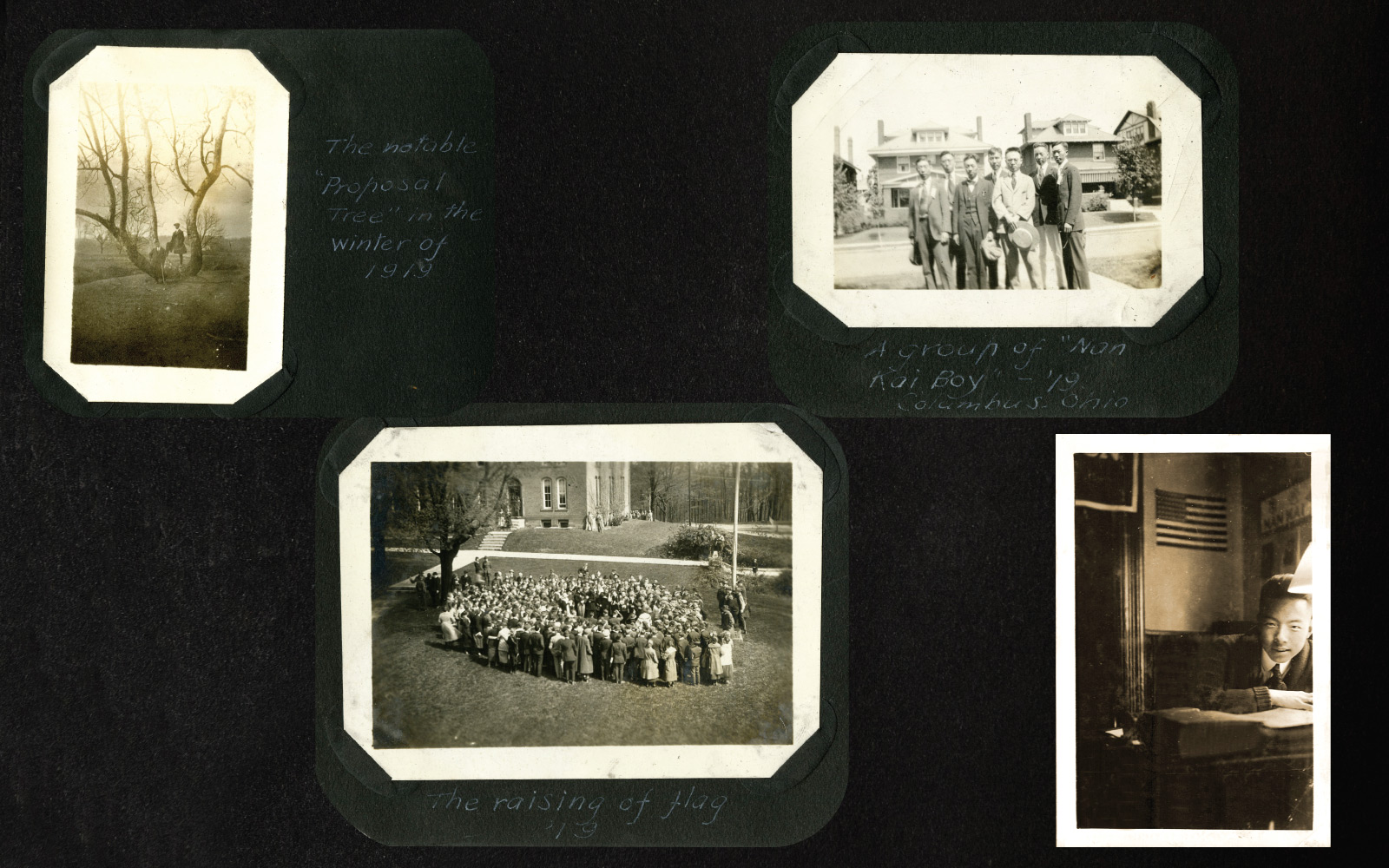

Top left:

Posing with the “Proposal Tree,” a legendary spot for romantic Denison couples in the early 20th century.

Top right:

Tsune Chi (second from right) spent the summer after freshman year taking classes at Ohio State in Columbus, where a number of fellow alumni from Nankai School also lived. This was June 1919, and the likely topic of conversation would have been about the “May 4th Movement” of 1919 in China, started by students in Beijing protesting the Chinese government’s weak response to the Treaty of Versailles. It sparked a movement toward nationalism and shaped China’s direction and leadership in the 20th century.

Bottom left:

Raising the flag on Denison’s academic quad. The flagpole was farther east then, before the footbridge from Chapel Walk.

Bottom right:

The young diplomat, “a studious chap” according to the 1921 Adytum. “He is a good mixer,” it continues, “and can appreciate and perpetrate a joke as well as any Yankee.”

Part 2: Gong and Neng: Making of a Statesman

Tsune Chi Yü 1921 was born in Hebei Province during the final year of a century of disruption and great losses for China, the results of outside forces of Western trade (two Opium Wars), Christian missionaries, territorial aggression from Japan (Sino-Japanese War), and also from political upheavals within China itself (Taiping Rebellion). As the future of China was being forged by its past, Tsune Chi was being shaped by the historic changes and events surrounding his young life.

The year of his birth, 1899, marked the outbreak of the Boxer Rebellion, a violent clash of cultures that did much to define China and its future relationship to the West. Anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian, the peasant insurgency was taken up by the Imperial Army but was defeated in 1901 by a combined force called the Eight-Nation Alliance, which included America. The Qin Dynasty never fully recovered, and in 1911, when Tsune Chi was 12, thousands of years of dynastic rule in China came to an end.

The Boxer Protocol provided financial reparations to each of the victors. In 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt made the decision to reduce China’s payment to the U.S. by $10.8 million. That money was repurposed to establish The Boxer Indemnity Scholarship, a program that taught English language and Western culture to China’s youth, and also subsidized students’ opportunities to be educated in America. Western education was being seen as the way forward.

Roosevelt saw the benefits of this program as “American-directed reform in China” to help promote American financial and political interests, while also promoting America’s international image. It became the most successful and consequential foreign study program in China’s history and set the stage for Tsune Chi’s education at Denison.

The Boxer Protocol also included territorial concessions to the victors—one of which, Italy, was given a district in Tianjin, administered by an Italian consul. Tsune Chi was educated at the Nankai School in Tianjin, and the proximity of the Italian Concession was likely his first exposure to the Italian culture and language, which would shape his future diplomatic career.

Nankai School in Tianjin was a recent (1904) and radical departure from the Chinese approach to teaching. It was modeled on Western-style college preparatory schools instead of traditional Confucian education, and its principal, Zhang Bolin, designed a curriculum that was aimed at helping students surmount the “five illnesses” that Zhang believed were afflicting China: ignorance, weakness, poverty, disunity, and selfishness. His solution was physical education, hygiene, group activity, science, and moral cultivation. Zhang employed the characters gong (public spirit) and neng (ability) to represent his

ideals for the school’s mission: civic responsibility, integrity, and the application of practical skills to produce leaders who could bring global respect and standing to China.

Tsune Chi Yü was in the class following Nankai’s best-known alumnus, Zhou Enlai, the skillful diplomat, statesman, and first Premier of the People’s Republic of China (1949-1976). Zhou Enlai was the speaker for his graduating class in June 1917, and his experience at Nankai has been described as the foundation of his lifelong intellectual vigor and personal resilience. That same educational experience, and the example of Zhou himself, would have influenced Tsune Chi’s determined and civic-minded path, though Tsune Chi Yü was a confirmed Nationalist rather than a Communist.

Following his time at Denison, Tsune Chi accumulated a series of advanced degrees in New York: a master’s in political science from Columbia, a doctorate in economic geography from New York University, and a doctorate in public law from Columbia in 1927.

Tsune Chi Yü served as Consul General of the Republic of China in New York and was remembered in his New York Times obituary for negotiating a permanent peace pact between two feuding Chinese factions in 1937 when then-Republican Beijing was “besieged by the Japanese.” They then agreed “to join in aiding their brethren in China to fight the invaders.”

He won the Victory Medal of the Republic of China; was president of the Chin Tsai Honorary Society in the U.S.; was a senior member of the Treaty Commission, Minister of Foreign Affairs; served as expert of the Chinese delegation to the Dumbarton Oaks Conference; was a delegate to the Paris Peace Conference in 1946; was an alternate delegate to the United Nations Assembly in 1949; and beginning in 1946, he was the ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary of China to Italy and Spain.