These are not the best of times for the United States Postal Service.

In December, the USPS issued an announcement in which it proposed to move First Class mail to a two- to three-day delivery standard in the lower 48. The proposal is the latest attempt by the postal service to cut costs and save the organization $20 billion by 2015. Last January, postal administrators announced their intention to close as many as 2,000 post offices across the country due to financial pressures.

They later announced a further 3,653 possible closures, most of them in small towns and rural areas. All in all, the service intends to review as many as 16,000 post offices, fully half of the 32,000 currently in existence, for possible closure by the end of the decade.

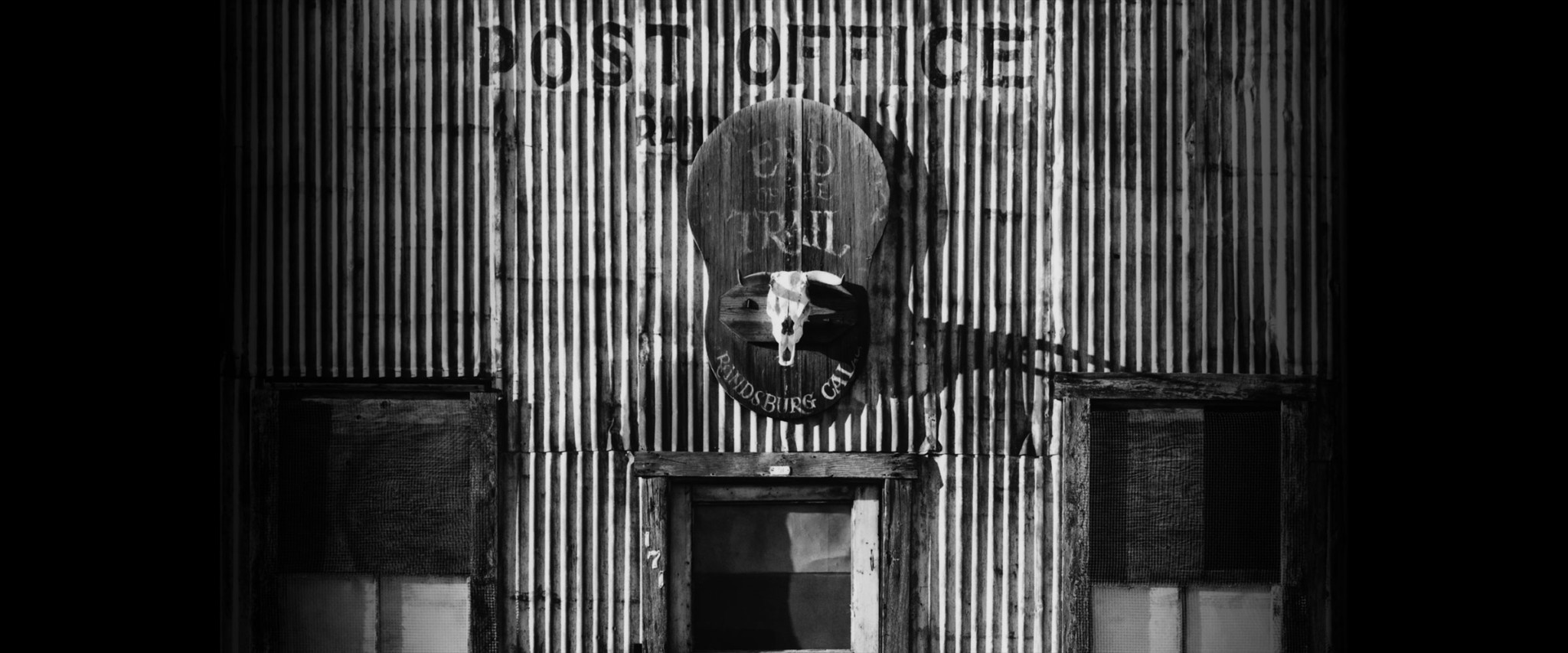

Granted, post office closures are nothing new. According to the website of the Museum of Postal History in Delphos, Ohio, there were, at the turn of the 20th century, 103 post offices in the three counties (Van Wert, Allen, and Putnam) served by the central Delphos post office. Today there are 30. But a proposed 18 percent reduction in one year, or a 50 percent reduction over the course of ten, would represent a radical trimming—some might even say a gutting. And the small towns and rural communities in which most of the closures will occur are not likely to come away unscathed. As Donny Hobbs, mayor of Lohrville, Iowa (pop. 369), recently said in testimony before the Postal Regulatory Commission, post offices provide small towns with everything from much-needed business services to a sense of local pride and identity. Lohrville itself is at risk of losing its post office.

Post Offices also serve as a vital social hub. “No other place brings in everyone from a community,” said Hobbs —a sentiment echoed by Bill Kirkpatrick, an associate professor of communication at Denison, who specializes in media and cultural studies. He asserts that the post office is one of the last remaining noncommercial spaces left in this country where people of all classes and ethnicities can come together. “There are very few public spaces like that left in America,” Kirkpatrick says. “When the post office is lost, what’s going to replace it?”

All of this goes a long way toward explaining why media coverage of the planned closures revealed such anger and dismay among small-town residents, who seemed little mollified by assurances that they would continue to receive basic services from post offices in neighboring communities.

It is possible, of course, that the USPS is simply using the threat of mass closures to pressure Congress, which regulates it, to enact legislation that would help shore up its teetering finances. But the economic challenges that the service faces are very real: postal officials say that the USPS currently loses $23 million a day, and it is expected to end the year 2012 with a $14.1 billion deficit.

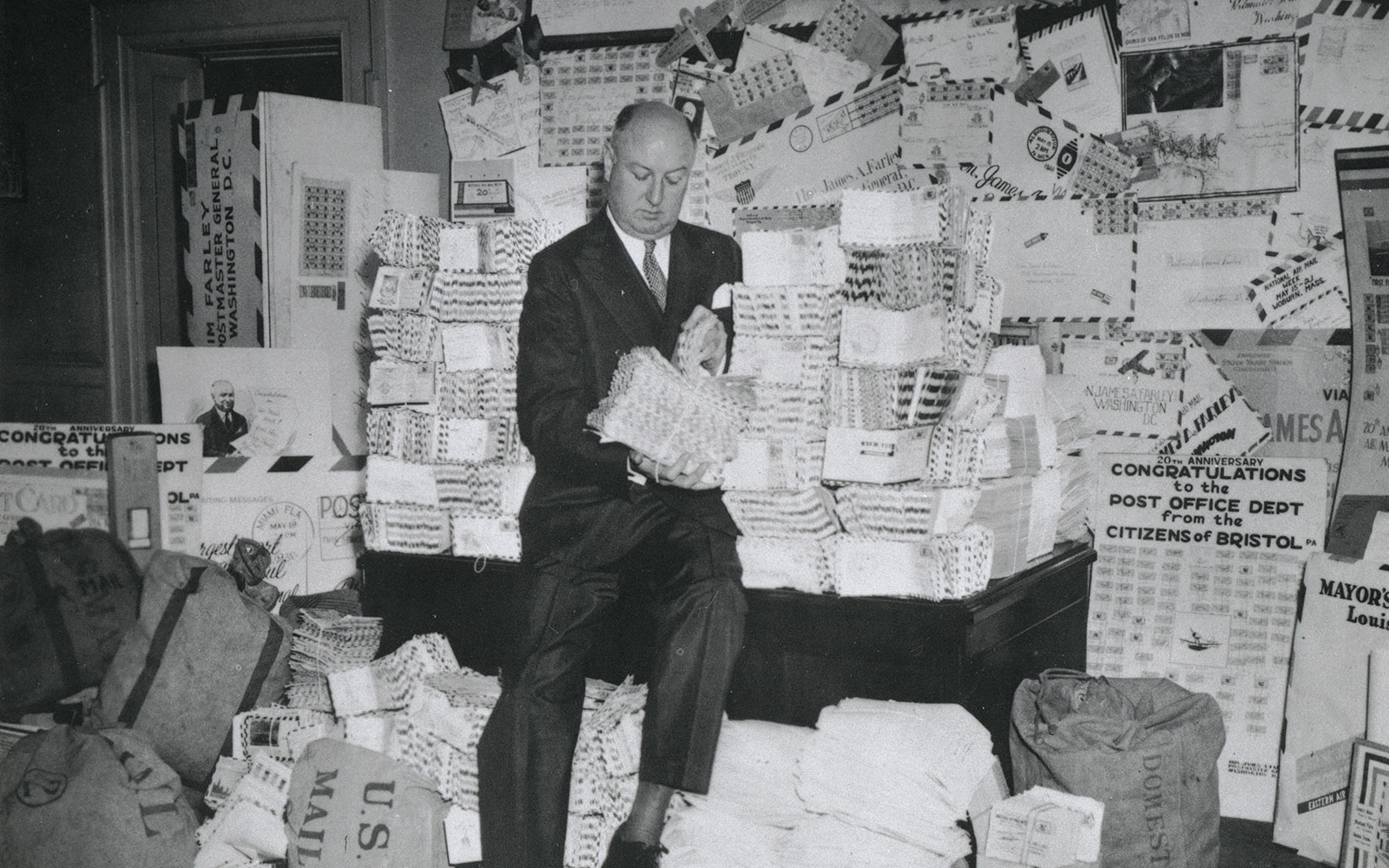

The factors underlying this desperate state of affairs are fairly straightforward. In recent years, the USPS has been hammered by competition from email and private carriers like UPS and FedEx: according to the service’s own figures, total mail volume dropped by 20 percent from 2006 to 2010, with first-class mail—the most lucrative sort, and the one over which the postal service has an absolute monopoly—plunging by 28 percent. In addition, Congress demands that the service pre-fund its Retiree Health Benefits Fund to the tune of approximately $5.5 billion a year, a requirement that the National Association of Letter Carriers would itself like to see ended. Federal labor regulations make it difficult for the service to shed or even reassign workers in order to cut costs or improve efficiency. Moreover, despite some recent innovations—the service recently announced for the first time that it would allow the likenesses of the living as well as the dead to grace its stamps—the government, for the last several decades, has had a hard time keeping the USPS relevant. In 1982, for example, the now-defunct Congressional Office of Technology Assessment prepared a study that warned of the need to respond quickly to the looming threat of electronic communications. In 2011, the USPS itself published a white paper in which it argued that the service ought to enhance its digital capabilities, and perhaps even move toward an Apple-like system of digital apps. Even so, it seems that the service and Congress haven’t managed to keep up with the ever-evolving digital revolution.

And yet the dire straits in which our nation’s mail service currently finds itself stand in stark contrast to its illustrious history. Few institutions have played such a pivotal role in the development of American society.

As Richard R. John, an historian of communications at Columbia University, recounts in Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse, the postal service was once regarded as an information superhighway and tool of democracy on a par with today’s Internet and social media. Nineteenth century pundits and political theorists considered the mail service a “mighty arm of civil government” without which the press would be “crippled and disabled.” They described it as the nervous system of the body politic, and labeled it a “great link between minds,” binding together an entire nation into “one great neighborhood.”

If you find all of this hard to believe, you’re in good company. No less an astute observer of American society than Alexis de Tocqueville, author of Democracy in America, was shocked to find that pioneers in backwoods Michigan in the 1830s were, thanks to the quality of their mail service, better informed of national events than residents of the Département du Nord, one of the largest and most commercially active administrative regions in France. “There is an astonishing circulation of letters and newspapers among these savage woods,” Tocqueville wrote. “I do not think that in the most enlightened rural districts of France there is intellectual movement either so rapid or on such a scale as in this wilderness.”

Given its current state, it is hard to believe that the United States Postal Service was once so central to American social, political, and intellectual life. In the 21st century, the USPS is hemorrhaging money and losing cultural market share at roughly the same pace as newspapers and bookstores.

There is both tragedy and irony to be found in the postal service’s gradual decline. At its inception in 1792, the system was viewed as a potential cash cow, one modeled after the royal postage service that the British re-created in North America during the colonial period. And it was for many years an engine of innovation, one that led to the establishment of the first large-scale road networks and later helped spur such transformative technologies as the railroad and the electric telegraph. The mere fact that the central government was able to establish and maintain so large and well-oiled an operation was itself considered a technological and administrative miracle. “It’s so much a part of our everyday life that we forget how revolutionary it was,” Kirkpatrick says. “This was their man on the moon.”

But much like the space program, the postal service has lost much of its luster. Perhaps its last great technological contributions came in the 1950s and 1960s, when it helped to introduce the barcode and optical character recognition, both of which are essential to tracking mail. Despite these achievements a half century ago, it is hard to see today’s USPS competing with the new-media companies that now dominate information technology and digital communications.

Nonetheless, amidst all the talk of operating deficits, closures, and possible reductions in service, there are signs that the USPS may be with us for some time to come. For example, a 2008 study by the RAND Corporation points out that the private carriers that have stolen so much of the service’s business continue to rely on the postal service to make final delivery of packages, tapping its national infrastructure and enormous labor force to save time and money.

And we have by no means reached the point at which all Americans have the resources, let alone the inclination, to carry out all of their written communications via e-mail and instant messaging. Those who suggest otherwise ought to consider the latest statistics from Point Topic, a British broadband analytics firm, which indicate that the United States ranks 27th in the world in broadband penetration—behind Macau, Estonia, and Slovenia. “We can’t do without the postal service yet,” Kirkpatrick says.

Nor, one might argue, should we hope to; and not just out of some misplaced sense of nostalgia for what the pop-culture critic Gary Beato, writing in the libertarian magazine Reason, called “an authentic, old-timey example of ‘heritage’ communications,” like a handwritten thank-you note.

It is telling, for instance, that when the Postal Regulatory Commission asked the Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank for economic and social policy research, to identify the benefits that the post office delivers to individuals and society, much of what it turned up had little or nothing to do with the delivery of mail. The Institute noted, for example, that letter carriers serve as a kind of neighborhood watch; that postal workers help reestablish contact with citizens after natural disasters like Hurricane Katrina; and that the postal service plays a role in government services such as voter registration and census completion. (Wildlife officials in many Midwestern states, including Ohio, still rely on rural mail carrier surveys to estimate populations of everything from rabbits to quail.) Most strikingly, it pointed out the role that the Postal Service plays in nurturing social links, fostering civic pride, and “promoting community identity through local post offices and services that support civic engagement.”

This is not a new concept. The idea that the postal service acts as a kind of social glue to help hold American society together is spelled out in the Postal Reorganization Act of 1970, which states that the “basic function” of the USPS is to “bind the Nation together through the personal, educational, literary, and business correspondence of the people,” and to provide “prompt, reliable, and efficient services to patrons in all areas… and all communities.” In Spreading the News, Richard John argues that in the 19th century, the precursor of our modern mail service created a national market by allowing businesses to conduct trade from the Atlantic seaboard to the Western frontier. Just as importantly, by disseminating newspapers, political pamphlets, Congressional newsletters, and personal correspondence the length and breadth of the nation at a time when no other form of long-distance communication was available, the service also enabled the formation of a shared national identity—and of just the sort of informed citizenry that is necessary for the proper functioning of a representative democracy.

The postal service is no longer the only game in town when it comes to spreading information and creating imagined communities across vast distances. Indeed, many people under the age of 30 now associate those functions exclusively with digital communications. Nonetheless, in smaller towns and rural communities, the post office remains not just the center of commercial activity, but also one of the few places where people can engage in face-to-face contact with their fellow citizens; where the postmaster keeps a pot of coffee brewing for customers; and where the letter carrier knows every child on his or her route by name. Lose that, and you lose a lot. “Community doesn’t just happen,” Kirkpatrick notes. “Community has to be nurtured; there have to be places where people can come together.”

A retreat from the postal service is, Kirkpatrick argues, both a retreat from democracy, and a retreat from our historic commitment to a shared national culture—a commitment that has, for much of this nation’s history, been represented by its postal service. Abandoning the symbol implies that we are abandoning the ideal. And that’s no small thing.

“We need a shared social commitment to keeping everyone in our society connected and able to participate in this democracy,” Kirkpatrick adds. “If we walk away from it, we’re walking away from something big.”

Alexander Gelfand is a freelance writer based in New York. He has written for The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and The Economist.