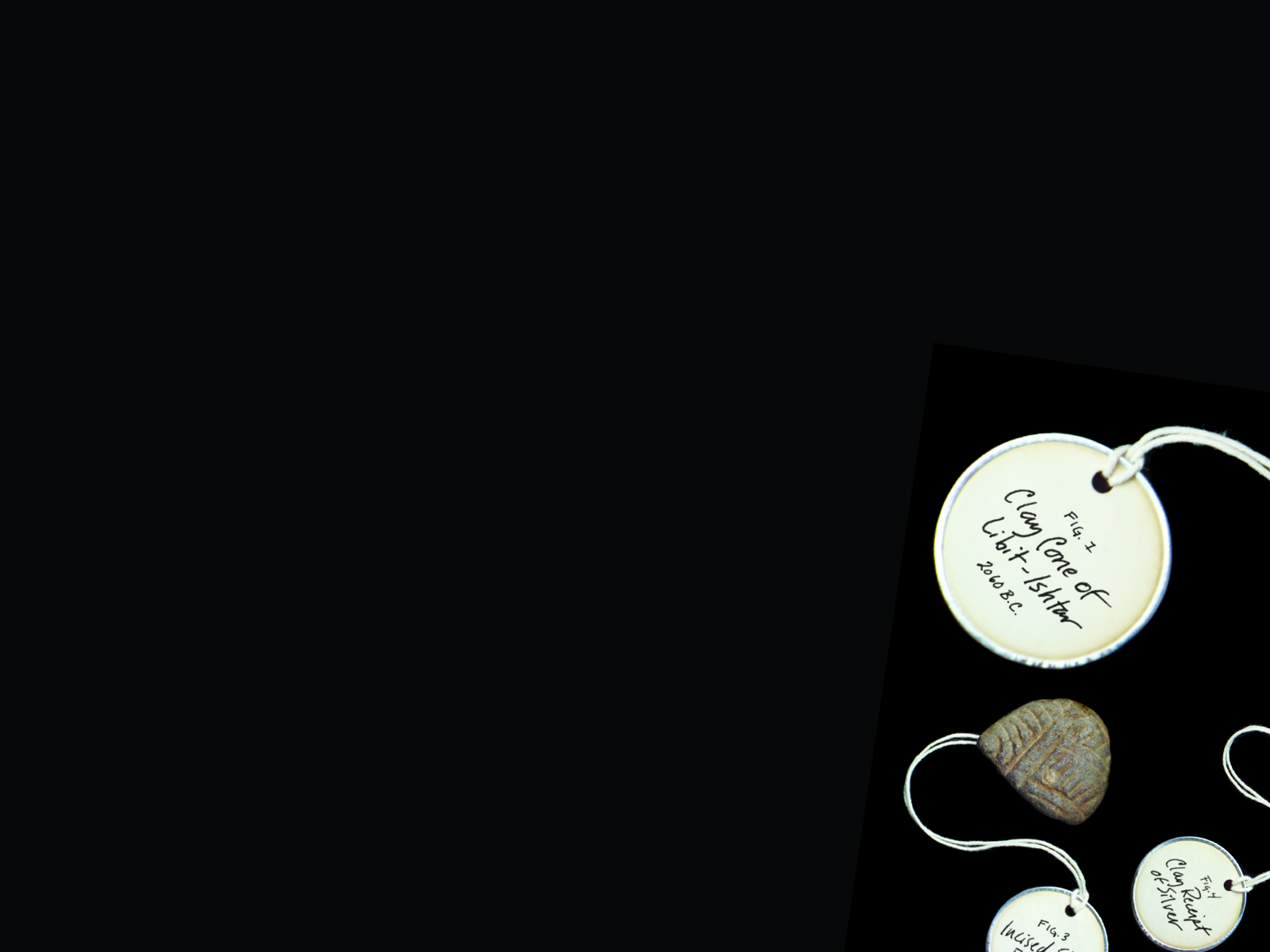

Figure 1-5

This four-inch-long clay cone is actually the 4,000-year-old cuneiform calling card of a Babylonian king named Libit-Ishtar. It was inscribed and then buried with a few backup copies inside the walls of his great temple in Ur in 2060 B.C., to tell future generations of the illustrious king’s pedigree and largesse. For the past year, it’s been housed within the walls of the Denison Museum in Burke Hall along with six smaller inscribed tablets of even greater age, all recent gifts to Denison by Lee Sharp Hart ’50.

Hart inherited the objects from her grandfather, E. R. Johnstone, who acquired his small collection of Babylonian artifacts from the noted archaeologist Edgar J. Banks in the 1930s. Banks, said to be the principal inspiration for cinematic archaeologist and adventurer Indiana Jones, brought home the spoils of his expeditions to ancient Babylon, now part of Iraq, but waning fortunes in the ’30s forced him to contact friends and colleagues who might be interested in purchasing the objects from his personal collection. Banks’s typewritten letter to Johnstone describes and translates Libit-Ishtar’s cone and notes its value as the most signicant artifact yet found from the era and civilization of the biblical patriarch Abraham, who was born close in both time and place to the cone’s burial in Ur. The smaller clay and stone inscribed tablets from 2350 B.C. (pictured above) were found elsewhere in the region and are pocket-sized cuneiform receipts recording everyday exchanges of goods from dairy products to slaughtered beasts.

References to Babylonian artifacts already in the Denison Museum database intrigued new Curator of Collections Anna Cannizzo, and led her to track down their numbered box in Burke Hall’s storage room. She found more clay tablets, small clay figures, and a very familiar-looking fourinch cuneiform cone. Also inside the box was a yellowed typewritten letter dated November 1937 to Denison librarian Annie Louise Craigie by the same Edgar J. Banks from whom the Johnstone Collection had been acquired. Banks succeeded in selling small shares of his treasury to individuals and institutions across the country during that period, and apparently someone in Doane Library was unable to resist his authoritative and romantic descriptions. Seventy years after its partition and dispersal, coincidence has brought two pieces of the archaeologist’s original collection together again in Granville, Ohio. Even more remarkable, the clay cone in Denison’s 1937 collection is the exact twin of the newly-acquired Johnstone cone—identical time capsules inscribed and buried 4,000 years ago by King Libit-Ishtar in the temple of Ur.

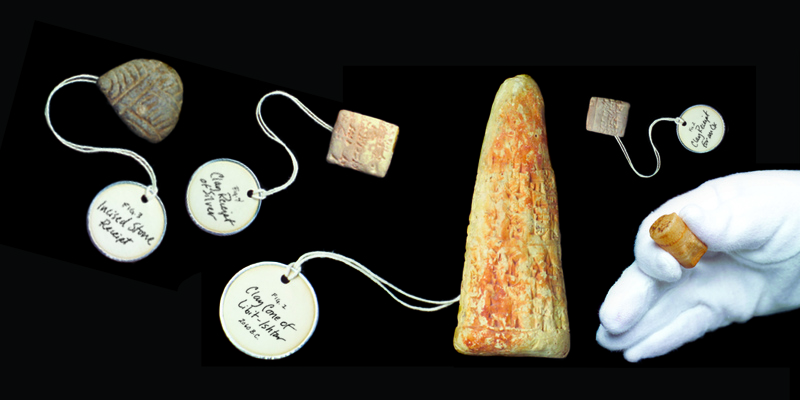

Figure 6

First issued in 1215, the Magna Carta is made up of 63 clauses that address the rights and responsibilities of English nobility. Its most enduring legacy is the right of habeas corpus, and it’s considered one of the most significant influences on the development of constitutional law. This rare edition of the Magna Carta, older than Copernicus and published before Gutenberg was born, was literally in Denisonian hands during fall semester. Even though its 1350 publication date makes it the sort of medieval masterpiece that’s usually locked away in an airtight archive, the Remnant Trust “Living Voices” exhibit brought this and nearly 50 other such treasures to Doane Library with the expressed purpose of being touched, read, leafed through, and maybe even caressed, all by bare hands. The mission of the Remnant Trust educational foundation is to “raise the spirits of each generation to think the grandest thoughts and be guided by the most profound idealism” through the hands-on availability of the world’s great ideas in original form.

- Babara Stambaugh

Figure 7

Between the 1920s and 1960s, give or take, college freshmen around the country were caught up in a craze not of their making. Beanies were foisted upon their heads to differentiate them from sophomores, juniors and seniors, who thought themselves far more mature than their beanie-wearing subordinates. Don Howland ’52 kept his for a while as a memory of campus life. He later gave it to the Alumni Affairs Office, which displays it alongside other Denisonian memorabilia in the Burton D. Morgan Center.

- Babara Stambaugh

Figure 8

This bronze buddha is about eleven inches tall, and has been dated to the tenth or eleventh century, Burma’s early Pagan period. He’s spent exactly forty of his nearly one thousand years on a dark storage shelf in Burke Hall, disguised as one of several “standing buddhas” in Denison’s notable collection of Burmese art. His real identity as a “walking buddha” was only recently uncovered when a conservator removed the crude modern base onto which he’d been mounted, along with a quantity of “green goo” packed under his right foot, revealing that the slight unevenness in his stance wasn’t a flaw in the original casting. Beneath the “goo” was a supporting strut designed to hold the right foot at a higher level than the left, in a deliberate gesture of walking. Buddha’s venerated status usually bars him from such earthly forms and activities as per-ambulation, but Burmese artists occasionally used this technique of shortening one leg in Buddha imagery as an alternative to the more familiar and human representation of placing one foot forward of the other. Few examples of three-dimensional walking buddhas exist, making the Denison image a significant one, and a newfound gem in the museum collection.

– J. H.

Figure 9

Bigger than a breadbox and heavier than the average briefcase, the Syllogiac 406 is a battery-operated portable logic machine. Designed for classroom use in the 1950s by philosophy professor Maylon Hepp (1946-73), this handcrafted proto-computer was intricately wired to test the validity of logical syllogisms (“Socrates was a man. All men have hair. Therefore…”). Hepp connected a set of “premise” dials to switches and banks of colored lights, and delighted in showing students the speed with which his Aristotelian robot would deliver its verdict. The machine’s smooth fruitwood cabinetry and ventilated masonite panels are evidence of the era in which it was built, as well as of Dr. Hepp’s meticulous craftsmanship and engineering skill. When Hepp retired in 1973, so did Syllogiac 406, which sat in a dark departmental closet for the next 25 years, until Hepp’s colleague, Tony Lisska, donated it to Denison’s archives.

– J. H.