On the morning of January 28, 1998, in a snow-blanketed stretch of wild high country along the Arizona-New Mexico border, Bobbie Holaday ’44 lifted the corner of a steel crate carrying an adult Mexican gray wolf. Holaday was 76 years old, and not a big woman. An adult male wolf can weigh more than 140 pounds. Still, Holaday had no trouble hoisting her corner of the crate and helping to carry it to a temporary holding pen set among the ponderosa pines. She had been working to make this day happen for 11 years; the wolf she was carrying toward its eventual freedom was anything but a burden. “I was just elated,” she says. “It was one of the most memorable days of my life.”

A memorable day in a memorable life, although Holaday herself is far too unassuming to put it that way. Holaday is now 85. With her no-nonsense haircut, oversized Harry-Potter glasses, quiet voice and surprisingly youthful smile — the smile of a slightly shy 12-year-old — she is hard to picture as the celebrated leader of a highly public citizens’ crusade to return the wolf to the wild in Arizona.

But Holaday has been defying expectations since her days at Denison. The group she founded, Preserve Arizona’s Wolves (P.A.WS), may have brought her national attention, but the sense of adventure and the habit of persistence that led to her effort on behalf of wolves, a quest a leading environmentalist told her would be impossible, is only one chapter in a story of quietly remarkable accomplishment. Through it all, she hasn’t lost her sense of humor. She delighted in telling me that the wolf she helped to carry that day, one of the first to be released into the rugged Blue Range, blew his photo op. When the door was thrown open, he turned tail and huddled in the back of the cage, unwilling to seize the opportunity. The same can never be said for Bobbie Holaday.

Holaday arrived at Denison, the daughter of a Baptist Minister, with no greater plans, she says, then becoming a “well-rounded community lady belonging to clubs and that sort of thing.” Still, a certain restlessness of spirit must have been there from the beginning because, when she graduated, she didn’t settle into the comfortable life she describes.

Instead, out of a sense of duty, she joined the Navy. The man whom she had married that previous February was already in the service, and “wasn’t that happy about it. He said he would prefer to have me just wait for him at home. I was never the ‘just wait’ sort of woman.” As a WAVE, Holaday cared for sick soldiers and sailors at Great Lakes Naval Reserve. She was honorably discharged in 1946 and upon her husband’s return they made a home in northern Michigan, where Holaday had two daughters and embarked on the volunteer work and social whirl she had envisioned.

But the marriage broke up, and in the ’50s, when proper moms were waiting at the door with a martini in hand, Holaday found herself with two daughters to support. She didn’t run back home; it seems unlikely she even grumbled much. She simply went to work. As with many women at the time, she found that her English degree qualified her, in the eyes of employers, for work as a secretary. “All my positions were initially secretarial,” she says. “I started as the office flunky.”

In 1956, Holaday packed up her daughters and headed to Arizona. She had no job — nothing, really — waiting for her there. But the West had been a romantic obsession with her family. (She recalls being captivated by the pictures in Arizona Highways magazine as a child.) Holaday checked into a Phoenix motel, left her daughters under the watchful eye of the owner, and went out looking for a job. She found one almost immediately and, after a few detours, ended up with Honeywell, where she would work for the next 28 years. She was a secretary until her boss suggested she take classes in programming at Arizona State University. The English major, who once thought her future was as a society matron, discovered she had a gift. She would eventually become a senior systems’ analyst, specializing in the most esoteric of computer languages — machine code — the basic, binary system of 1s and 0s that underlies all computer systems. Senior systems analysts make good money, but they also sit a lot. When her youngest daughter got after her to be less sedentary, Holaday joined Honeywell’s hiking club, taking two- and three-day backpacking trips into the state’s expansive wild country. “I realized I was enjoying all this [wilderness],” she says, “but I wasn’t doing a darn thing to help it.” Through the Arizona Wilderness Coalition’s “Adopt-a-Wilderness Program,” Holaday adopted the Hell’s Gate area, a wild stretch of mostly federal land in Central Arizona that includes a thousand-foot-deep canyon, waterfalls, emerald pools and some nearly impenetrable brush. It also includes ranchers. Holaday’s goal was to have the Hell’s Gate declared a wilderness area, a federal designation that protects it from depredation and development. “But the ranchers were tremendously opposed to it,” she remembers.

Ranchers and environmentalists often seem to be staring at each other from opposite sides of a thousand-foot-deep canyon, content to hurl accusations across the divide. But Holaday took a different approach. She set out to meet her opponents — on their ground.

Pat and Raymond Cline ranched in the Hell’s Gate on public land so rugged most people would have taken up another trade. Such land breeds tough, no-nonsense people. When Holaday drove out to meet them with friend and fellow activist Tom Wright, she admits, “I was trembling because I knew how fiercely they were opposed to what I was doing.”

Pat Cline, now widowed and living in Payson, Arizona, remembers that day well. “They were city folk,” she says. “I said, ‘Bobbie, have you ever seen your wilderness? Do you know a thing about it?’ So we saddled up our horses and off we went.” They spent eight long hours in the saddle that day, remembers Holaday, riding up to the Cline’s winter camp while Pat grilled her: “I said, ‘You know what kind of brush that is? No? You have to know about that brush. Bobbie, how can you push a wilderness if you don’t know a damn thing about it?’ Well, what do you think she did? She went straight to ASU (Arizona State University) and enrolled in range plant identification and management classes. She got right with it.”

The trip was, as unlikely as it seems, the start of a beautiful friendship. Holaday came to understand the challenge ranchers faced in the Hell’s Gate and that they needed special rules to allow them to function in the rugged country. Thanks to Holaday’s persuasions, the Clines realized that, if set up properly, the wilderness designation actually could protect their way of life. They became supporters and spread the word among ranchers. In 1984 the government designated the Hell’s Gate Wilderness Area with rancher and environmentalist support.

It was a remarkable achievement, which Holaday is quick to shrug off. “There’s nothing complicated about it,” she says. “They’re human. You’re human. And what you have in common is you both love the land. Once you realize that, you can find a way to work things out.”

Holaday would use the same approach when she successfully worked to establish the Eagle Tail Mountains Wilderness Area in 1990. But the middle ground would prove far more elusive with the next cause to capture her attention.

It all started, she says, “because she needed a new dog.”

On the day I visited, Holaday gave me a tour of her home. There were, I’m sure, chairs, tables and other furnishings, but I can’t remember them. All I can remember is wolves: wall-to-wall wolves, on posters, in photographs, on plates, on the towels, on fridge magnets. The density of wolf paraphernalia was overwhelming. All through our interview, new objects would suddenly pop into focus: wolf coffee cups, wolf statues, stuffed animal wolves.

Holaday seemed to regard the entire collection, much of which has been given her, with some amusement. When I asked her how many stuffed wolves were on her bed, she replied, “I’m not sure I want to know.” (The answer was about 40, not counting those on the dresser.)

You might gather wolves have been a life-long obsession. But Holaday’s interest actually began, after retirement, when, looking for a new dog, she decided to get one that was half wolf.

Luke, a wolf-dog pup, was soon followed by another, Jato. Holaday was enthralled with her two pets, but realized she needed expert advice. “They’re not like other dogs,” she says. “They’re very smart, too smart for their own good sometimes. And you have to understand that they’re predators.” (She adds she would never recommend a wolf-dog for anyone with children or who doesn’t have a lot of time to devote to one.)

Holaday joined a club for wolf-dog owners and, through it, learned Arizona was investigating whether the Mexican gray wolf should be returned to the wild. In the first half of the 20th century, the wolf had been relentlessly exterminated. No one was sure when the last wolf had been killed in the state, but experts say it was no later than the 1970s. The only Mexican gray wolves left in the United States were in captivity.

The more Holaday learned about the situation, the more she was convinced the wolf population needed to be ‘recovered’ as animal management specialists call it. When she asked Terry Johnson, manager of the Arizona Game and Fish Department Endangered Wildlife Program, if a citizens’ group supporting the wolf’s reintroduction would help, he responded, “It sure wouldn’t hurt.”

That was all Holaday needed. She organized P.A.WS, first by recruiting members locally, and then building it into an organization with more than 500 members from across the United States. P.A.WS gave the wolf a critical voice in the press and at the seemingly endless series of public hearings held to consider its return. When some opponents claimed the wolf still survived along the Mexican border, which would have made recovery unnecessary, Holaday and other P.A.WS’ members trained to survey for wolves. This required learning how to howl like a wolf (so you could see if a wolf howled back, of course). Sitting in her kitchen, I convinced Holaday to demonstrate for me, and while I can’t say if the long, rising and falling howl she managed was accurate, I can testify that it was impressive. Holaday faced tremendous public hostility as the leader of P.A.WS. It’s hard to imagine, but the small, soft-spoken woman I met in Phoenix has been publicly compared to the Nazis, her group branded ‘green terrorists’ by opponents. “I’d pick up the phone and somebody would say, ‘Why the hell don’t you get a life?’” Holaday says, as if recalling an encounter with a mildly annoying sales clerk.

Local residents claimed the wolf would not only threaten their livestock, but the safety of their children. “I think the wolf is a symbol to ranchers of everything that’s happening to them. What’s really happening to them is economics — they’re going to become extinct,” says Jan Holder, who was ranching with her husband, Will, in the recovery area at the time. “The wolf is a symbol of a way of life disappearing. It’s the final blow.”

On the other hand, many wildlife experts believed the Mexican gray wolf faced extinction if its population couldn’t grow beyond the confines of zoos, and also felt the wolf was a necessary part of the eco-system, pruning Elk and other game herds of the weak and unhealthy. “They really fulfill an ecological niche that no other predator does,” says Don Hoffman, past head of the Arizona Wilderness Coalition, who lives in the Blue Range and initially told Holaday opposition would be so fierce he doubted she could succeed.

Despite the hostility, Holaday did what had worked for her before: she reached out, organizing a task force continued from page 29

force of ranchers and environmentalists that met for a year and a half. “That was the greatest lesson I learned from her, the way she approached people with respect,” says David Bluestein, a Honeywell aerospace engineer who was an early member of P.A.WS. “People would literally walk up and blast her, and she would smile and say, ‘I understand your point of view.’ She would deflect, and she wouldn’t take it personally.” Hoffman adds, “For an unassuming woman, she’s actually fearless.” The recovery Holaday supported was to introduce the wolf as an ‘experimental population,’ a designation providing less protection than reintroduction under the Endangered Species Act. This angered some environmentalists, but Holaday believed a more strident position was politically untenable: “I said, ‘Fine. You can go to heaven with your principles, but I want to see wolves on the ground.’”

Despite her best efforts, Holaday was unable to find an acceptable middle ground. A few ranchers, like the Holders, decided they could live with the wolves by changing their livestock management practices (mostly moving their cattle more frequently), but most remained adamantly opposed. At the end of the task force, several left angrily.

“I think that was one of her greatest disappointments,” says Hoffman, “that she couldn’t find some sort of consensus.” Holaday says only, “We never convinced some people, and we never will.”

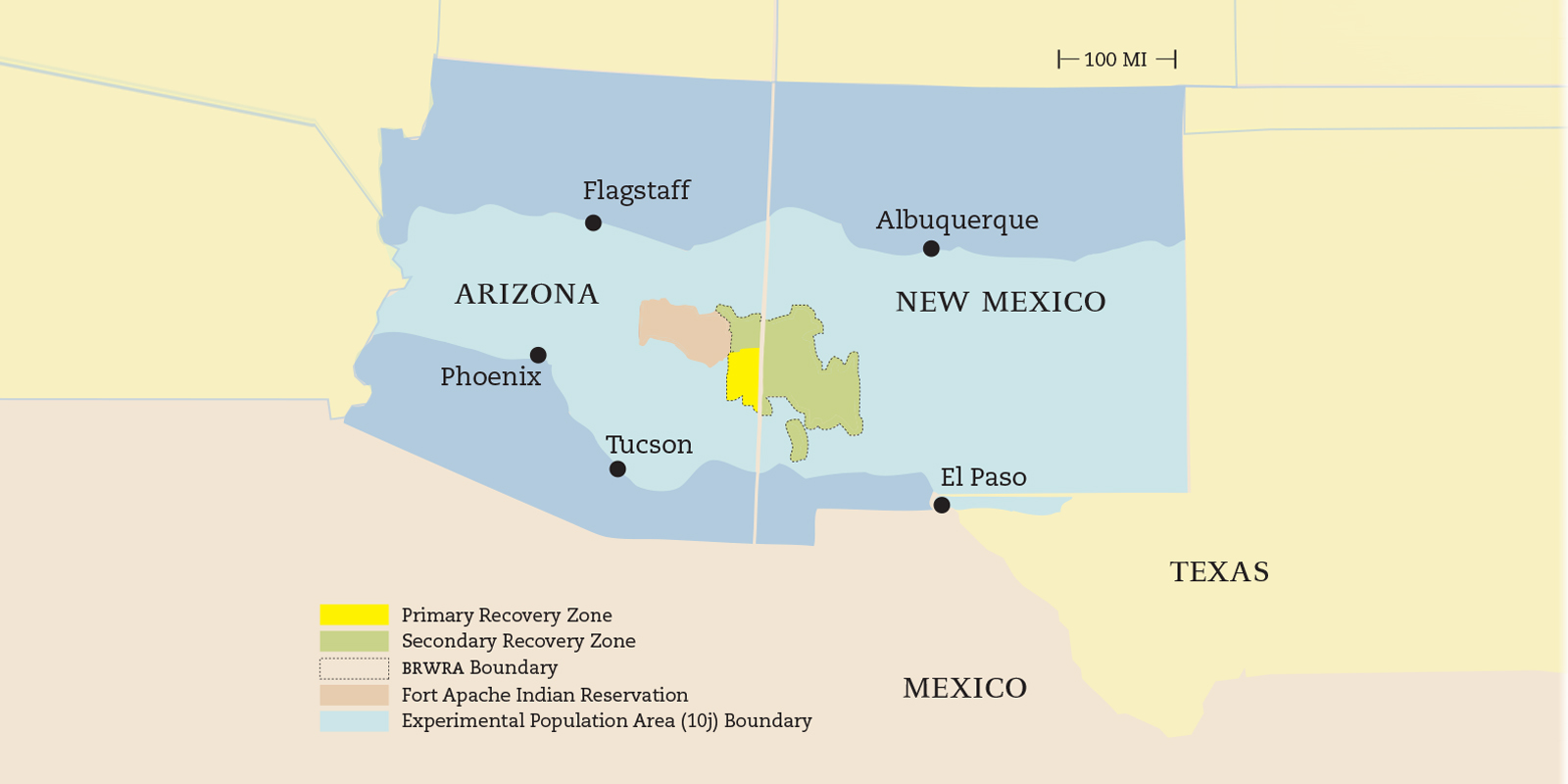

To try to understand the depth of the disagreement, I traveled to the Blue Range Wolf Recovery Area, where Shawna Nelson and John Oakleaf, who work in the Mexican Wolf Recovery Office in Alpine, took me out to look for wolves. The Blue Range is part of the Mogollan plateau, an elevated landscape of pine forests, small lakes and grass lands that resembles Colorado more than the desert most people think of when they hear Arizona. The land is largely federally owned, but ranchers have been here for more than a 100 years. On a bright September day we drove along sweeping meadows where cattle grazed placidly, through stretches of thick timber where the aspens stood out like white signposts among the ponderosa pine. Later, I would travel deeper into a far more rugged part of the range to meet with Hoffman. But as Nelson, Oakleaf and I scanned a tree line on the far side of a swath of open land for the wolf that our radio receiver told us was out there (at least one wolf in each pack wears a radio collar) but that we would never see, the countryside felt oddly balanced between civilized and wild.

I understood something Oakleaf had said earlier: “Wolves more than any other animal symbolize wilderness. The attitude people feel toward them reflects their attitude toward the wilderness. We’ve gone from civilizing the wilderness, which meant getting rid of the wolf, to preserving the wilderness, which means bringing the wolf back.”

For many of the families involved in the civilizing, it amounts to a repudiation of their heritage. It’s not surprising that, in the end, Holaday wasn’t able to convince most ranchers.

But P.A.WS and other advocates were able to convince most Arizonans. Polls showed a majority favored the wolves return, and on that snowy morning in 1998, it happened. Holaday was given a place of honor, along-side Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt, among others, carrying one of the first wolves to the holding pens. Then, as she always said she would, Holaday disbanded P.A.WS when the wolves were released into the wild.

It would be nice to end the story here. The first wolves bounding back into the snowy forest. But real endings are hardly ever so tidy. The wolves still faced tremendous hostility. Soon after they were released, shootings began. Other wolves got hurt or wandered afield. Only one of the original 11 survived in the wild.

The government released more and, slowly the population began to take hold. At the end of 2006, there were 59 wolves in 11 packs in the recovery Area. Forty-six of those had been born in the wild. “At some point the question changes. It goes from how do you get rid of the wolves to how do you live with the wolves,” says Oakleaf. “I’m not sure we’re there yet, but I think people are starting to accept that the wolves are here.”

Holaday doesn’t get up to the ‘Blue’ much anymore. The drive is a long one, and since her knee was replaced a few years back, she doesn’t feel up to it. Her battered camper with its “Little Red Riding Hood was Wrong” bumper sticker still sits in her driveway, but it’s used only for local trips.

For the first few years after the wolves were reintroduced, however, she camped regularly on Luna Lake just outside of Alpine, traveling with Blizzard, the snow-white half-wolf who has replaced Luke and Jato. She wrote much of her book, The Return of the Mexican Gray Wolf: Back to the Blue, published by the University of Arizona press, in longhand sitting by the lake.

David Bluestein and other friends would join her, and at night, they would put on one of their howling cassettes. Blizzard would start howling, and, eventually, so would they. Sometimes, out of the darkness, in the distance, a wolf would howl back. “That,” Holaday says, “made it all worth it.”