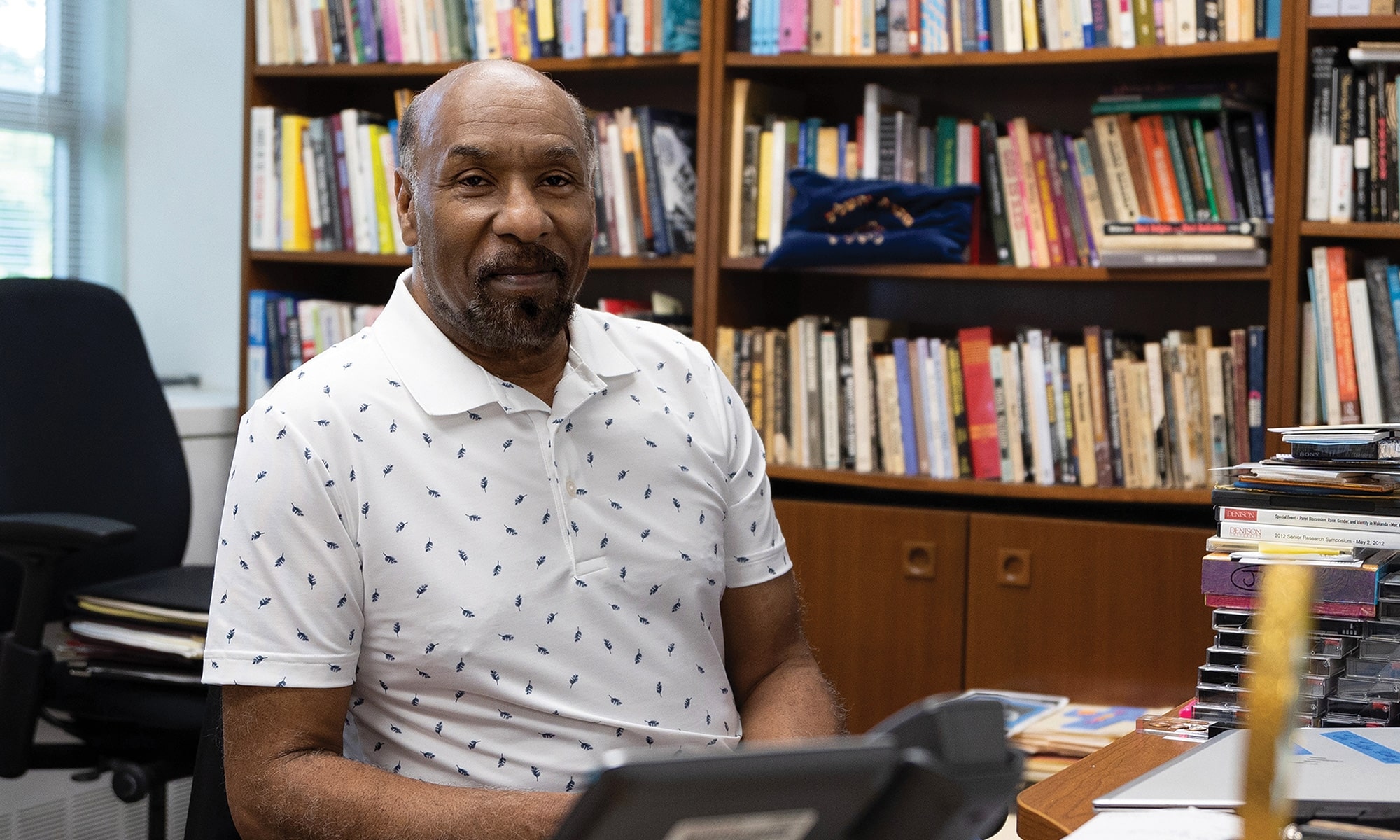

The office-within-an-office of John Jackson looks like, and is, a sanctum: books tightly shelved and loosely stacked, artifacts like talismans on the surfaces. True to its occupant, it’s a quiet space — personal, distinctive.

Knapp 209B holds nearly a half-century of Jacksonian history, and echoes with the close conversations, mentoring, and political strategizing with students and colleagues who have sat across from his desk, experiencing what emeritus Bill Nichols describes as Jackson’s “tact and great gentleness” as well as his reliable moral compass.

Jackson’s first Denison office had an unobstructed view of the Welsh Hills from the fourth floor of Slayter. He came from Harvard Divinity School in 1974, hired as associate Dean of Chapel, and his first few years were busy with preaching and teaching and advising student volunteers in DCA, the Denison Community Association. He and his wife, Rita, were also the young parents of a baby boy.

Jackson was initially appointed in the Religion Department, not Black Studies, a program which had begun in 1968 in the form of evening classes taught by Bill Nichols and Jack Kirby. It wasn’t until 1978, when Jackson was elevated to Dean of Chapel, that President Good convinced him to stay on at Denison while he pursued his doctoral studies, and to help further develop the still young Black Studies program.

OBJECTS: A few of the pocket-sized objects on display, these from Rwanda, Kenya, Mexico, and possibly Granville.

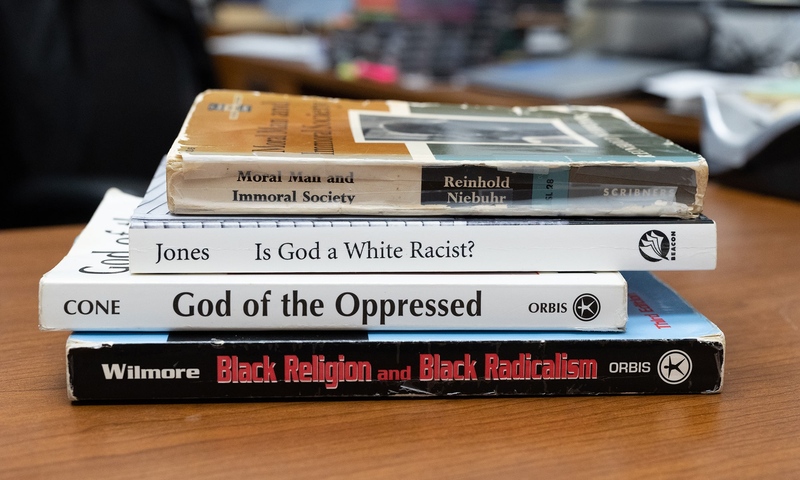

BOOKS: Four of the most frequently consulted books in Jackson’s office.

In this incremental way, Jackson found his work and purpose shaped. His entire life before divinity school had been spent in Alabama, including his undergraduate years at Miles College, a historically Black liberal arts institution with roots, like his own, in the Christian Methodist Episcopal Church. When he was young, his grandmother opened his eyes to the contradictions of slavery in a country that declared itself a place of freedom. In college he was strongly influenced by reading James Cone’s Black Theology and Black Power, which brought deeper meaning to his study of religion. And he recalls how the daily realities of apartheid in South Africa moved him to decide that his academic background in religion and sociology “had little meaning without exploring movements for social justice.”

His path through religion grew in complexity, and in this unlikely, predominantly white northern university, Jackson sensed opportunity. Denison was a small community still very early in its journey with multicultural engagement. It was open to possibilities, but there were plenty of awkward and arduous hurdles. He was not a rabble-rouser, but neither did he back down in a challenge. He was looking for ways to effect change, and with a largely supportive administration, Denison was a place he could put his skills and beliefs into practice and speak truth to power.

As a boy in Opelika, Jackson learned early that entering the front door of the pharmacy could be an invitation to trouble, but he knew he could use the side alley and knock on a window to get his family’s prescriptions. Looked at in this way, Jim Crow Alabama could be a proving ground for risk assessment and creative problem solving.

Jackson’s experience and disposition alerted him to the power in careful deliberation. His colleague and friend Bill Nichols underscores this point: “John’s background is in the South. And I think that prepared him to recognize hidden danger. He worked with indirection, not trying to be a hero.”

Building coalitions with common interests is not only Jackson’s style, it’s how things get done in an institution. His commitment to the mutual support between Black Studies and Women’s Studies has been a model at Denison through the decades, and an early policy success is one of his most enduring. Having convened a small group of faculty to develop a plan from an idea, Jackson helped guide Denison to adopt a diversity requirement as part of its general education standards. In 1979 this was a first in American higher education — a bold accomplishment for Denison and an example for many other institutions.

When the requirement was omitted in a curriculum restructuring in the early 2000s, Jackson and allies came back with the existing “Power and Justice” requirement, an update and recasting of the original plan. Persistence, vigilance, and pressure carefully applied: some of the lessons of John Jackson as he retires this spring. His legacy is now a part of Denison’s DNA: a community more thoughtful, more aware, more humane, and stronger.