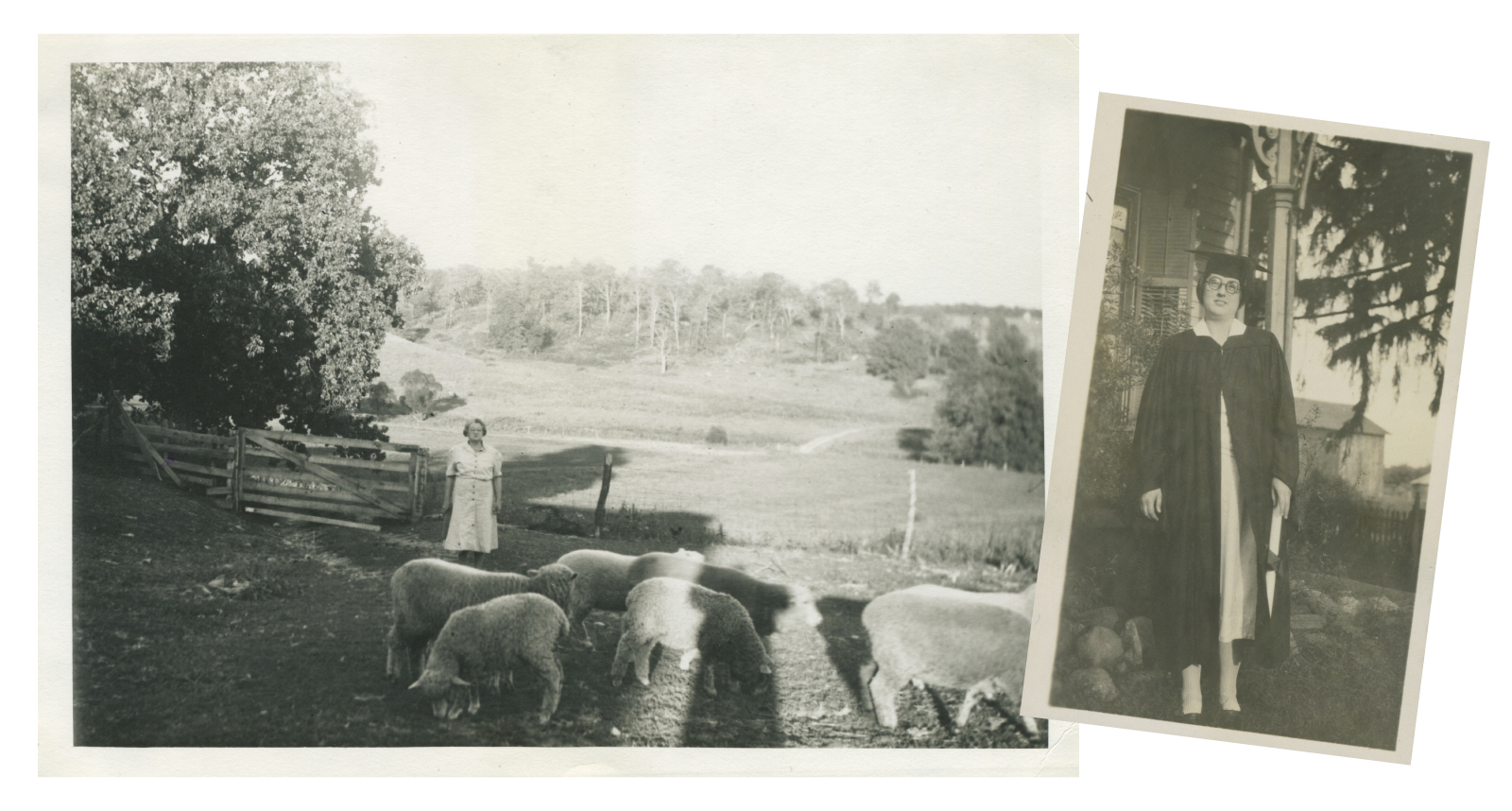

Pat Rolt-Wheeler Robins ’53 walks through the yard of her old family home.

It’s a warm fall day, and dry leaves scamper across the yard and in the woods just beyond. She’s smiling, even though, just last week, she lost her sister, Ruth “Anne” Rolt-Wheeler Skidmore ’48, to cancer. But today she’s remembering their childhood spent on this farm northeast of campus, in a white farmhouse, both of which are now a part of Denison’s Bio Reserve. It was here that she spent her childhood and teen years before heading across the street to Denison for her degree.

The Bio Reserve today is 360 acres of flora and fauna, but nearly half of that was once the Hobart family farm, or more simply, Pat and Anne’s backyard playground.

Today, students and faculty can be seen trekking along the trails with nets and notebooks, studying everything from the spotted salamander to the tadpole population in the area, and community members tromp through with their dogs. But this land was once occupied by horses, cattle, sheep, pigs, chickens, Barney the border collie, and Peggy, Pat’s pet goat, who once stood atop the chicken house and danced around until the shingles fell off.

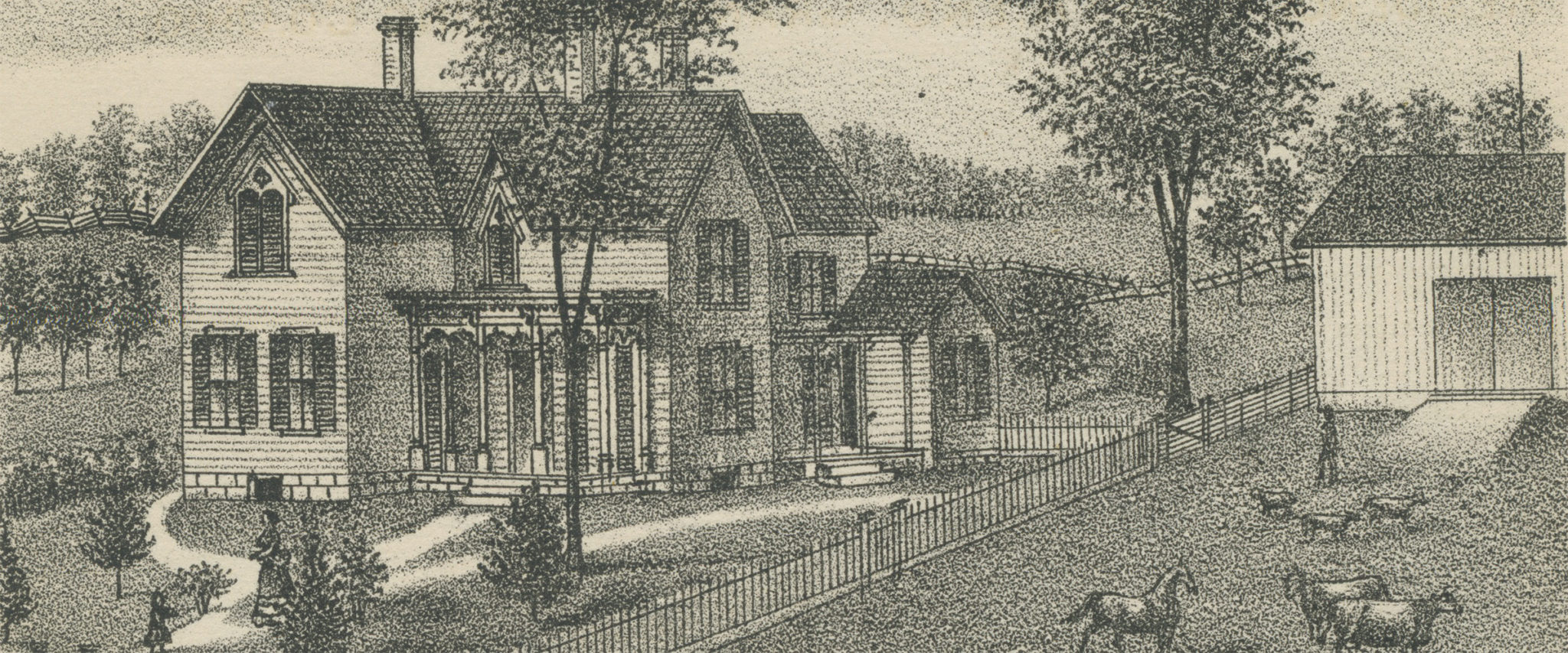

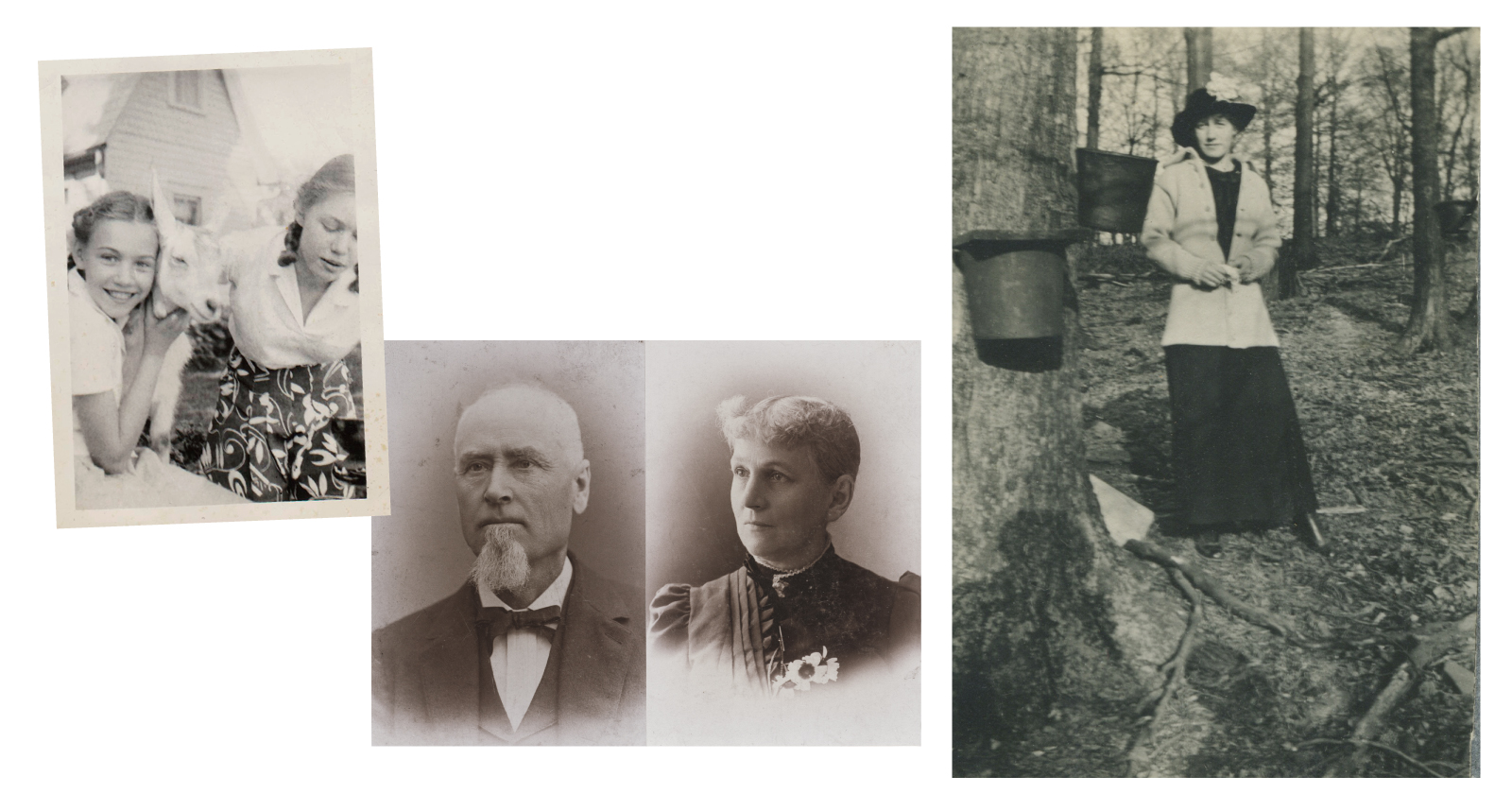

The farm had been purchased in 1849 by Pat’s great-great-grandfather, Giles Hobart, who passed it on to her great-grandfather, Henry Hobart, who willed it to her grandfather, Fred Hobart. Fred left the farm to Pat and Anne’s mother, Ruth Hobart Rolt-Wheeler ’27, and Ruth’s sisters, Ethel Hobart Breene ’21 and Dorothy Hobart Cannon ’25, with a lifetime residency for his wife, Anna. After Fred’s early death at age 46 in 1918, Anna embraced the role of businesswoman and farmer. Anna had attended Shepherdson College for Women in the 1890s, before it became part of Denison, but she left to get married. “Grandmother was a capable and determined woman who made joint decisions with Fred about most farm additions,” Pat says.

The family Christmas tree was usually a tree from campus brought to the women by Denison maintenance staff.

The oldest Hobart daughter, Ethel, left Granville after her Denison graduation and taught in Montana and California, where she died at age 103. The middle daughter, Dorothy, majored in chemistry and completed nurse’s training at Johns Hopkins University. She became director of the private-duty section of Columbia University Medical Center in New York City. Dorothy always spent her month-long vacation at the farm until she married in her 40s.

Pretty and vivacious Ruth left Denison early to get married, but after several years, her marriage failed and she, Anne, and Pat returned to the farm to live. A month before Anne died, Anne sat at her kitchen table and discussed her mother. “She had foolishly gotten married instead of finishing college,” said Anne. So Ruth went to Denison to complete her degree. It was 1933, and the little girls, then 2 and 6, quickly adapted to farm life.

It’s hard to imagine the home, as it is today, without electricity or indoor plumbing. But that’s just how Pat remembers it. Its placement on the outskirts of the village meant it didn’t have electricity until the summer of 1939—which meant the introduction of a radio on a small table in the dining room. “That was a treat,” says Pat. So was the introduction of a washing machine for Grandmother, who had spent most of her life washing farmhands’ clothes with a scrub board.

Prior to 1939, the women of the home read by gas lamps (there was a well on the property that provided free gas) and headed to bed by candlelight. “The village couldn’t foresee the modern farm,” Anne said, so Granville’s decision-makers didn’t consider providing electricity out in the country. But the Hobart farm had always been ahead of its time. The girls’ grandfather, Fred, owned one of the few large farm scales in town. He also built the first silo in the area and developed what was then an innovative cow barn with troughs (which can still be seen in the old red barn) behind the cows for easy cleaning and a walkway between them to simplify feeding. He owned a cider press and sold cider in town. Maple syrup, too. And he delivered milk and cream to the College. After his death, hired men did much of the heavy farm work, and at threshing time, Grandmother had to place two leaves in the dining table in order to feed 14 men, plus her own family. One constant was Mr. Falk, who couldn’t read or write, but he was always good for bringing the town news back to the farm from the pool hall on Saturday nights. He lived in separate quarters in the house with access to his own private stairway.

The Hobart farm, made up of 100 acres on the west side of Route 661 and 50 on the east side (now Homestead land) had close ties to the village and to Denison. One of the barn stalls on the property held an old sleigh that used to carry Santa Claus down Broadway every year at Christmas, and lying deep underneath the layers of asphalt on Broadway is rock from a gravel pit owned by the Hobarts. Even the family Christmas tree, which was lit with real candles on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day—“only when someone was in the room with a bucket of water,” says Pat—was usually a tree from campus brought to the women by Denison’s maintenance staff after the students had gone home for break.

Ruth not only helped her mother on the farm and raised Pat and Anne there, she was also employed at Denison as director of dormitory maintenance. She was charged with making sure rooms were fully equipped, that male students had linens and towels (women were responsible for their own), and that their living spaces were in working order. She oversaw maintenance crews, cleaning staff, and those working “bell duty,” students charged with answering the one phone in the residence hall and calling for the person requested.

In return for her service to the College, Ruth had job security (welcome in the Depression era and during WWII), free tuition for Pat and Anne, and first picks of the student leave-behinds at the end of the school year, which meant the girls often had elegant sorority gowns for dress-up. Ruth’s granddaughters remember dressing up in later fashions: satin dresses of the ’50s and floral dresses with sweetheart necklines and flowing skirts.

“Mother didn’t want the land to be used for houses, so she was thrilled to have it become part of the Bio Reserve.”

As Pat walks through the house, she shares stories of her life there. She remembers her mother’s chair and where it stood in the dining room. She remembers the eight-party phone line. She remembers the potbellied stove with the top grate that sat in the dining room and always held a tea kettle. And she laughs when she remembers Anne’s embarrassment when the pastor stopped by, and they had baby pigs warming themselves behind the stove. “Anne was mortified that we had pigs in the house.”

Pat finds a few surprises in that house she knows so well—a bathroom where her grandmother’s room used to be. The black walnut wood trim now painted white. But some things in the house, she finds, are just the way she remembers them. Like the stairwell banisters that she dusted as a child and the stairs themselves, which she fell down when she wore a black dress and opera pumps during sorority rush. Even some of the lighting fixtures remain. “They had beautiful things for farm people,” she says. Sterling silver and painted kerosene lamps. Victorian furniture and marble-topped tables. A dresser marked with the “Granville Manufacturing Company” and a date of 1805. These heirlooms have since made their way to new generations.

Nice things aside, this was still the Depression era, and later, war time. Even so, the girls never remember being hungry. “I don’t remember being deprived,” says Pat, “but we had very, very little money.” The farm provided nearly everything—meat from the livestock, potatoes from the ground stored in the cold cellar, peas, beans, corn, sweet corn, asparagus, strawberries, onions. “The farm produced a lot,” says Pat. “And Grandmother canned.” Sugar was rationed in the war, Pat says, and so were shoes. Grandmother went without new ones, because Ruth needed presentable shoes for work and the girls were growing so quickly.

And as they grew, they were expected to contribute. That meant pumping their own water when the windmill stood still, milking the cows, planting and harvesting the garden, and doing nightly dish duty. Their reward was a remark from Grandmother: “Do it again,” which meant they had done a good job.

Like their grandmother, aunts, and mother before them, Anne and Pat headed down the road to Denison, eventually leaving the farm behind for more schooling and families. Pat earned a teaching credential at Denison but eventually went on to Loyola Marymount in California, where she pursued aerospace engineering and worked for Hughes Aircraft for most of her career. Anne became a teacher, earned her master’s at Ohio State, and was head of the English department at her local high school.

After Anna Hobart died in 1953, Ethel sold her share of her farm to her sisters. In 1962, Ruth and Dorothy decided to stop farming, and they placed an ad in the Granville Sentinel to promote the sale of all the farming equipment. By 1963, the sisters were negotiating the sale of the house and their 150-acre family farm to Denison. They settled on a sum of $65,000—$55,000 to be paid in cash and $10,000 to be paid in kind, an agreement that allowed Ruth to take up residence in Stone Hall for several years. Dorothy, now a widow, bought a house in Newark. Ruth retired from Denison in 1972, and “It took three men to replace her,” Pat says proudly.

“Mother didn’t want the land to be used for houses,” says Pat, “so she was thrilled to see it become a part of the Bio Reserve.” (In an interesting twist of fate, Anne’s granddaughter, Alison Johnson ’04, lived on the Homestead for one and a half years.) That open land means Pat and future generations of the family can come any time they like, to walk around the family farm. When Ruth died in 1993, it gave the family closure to tour the property the week of her funeral.

Now with Anne’s passing, on this warm fall day, Pat does the same.