It’s a warm Sunday morning in August at Seventh Metro Church, on the corner of North Avenue and St. Paul in Baltimore, Maryland. Ryan Preston Palmer ’92 is telling his congregation a story of revival and transformation—of the actual revival that was held in his church the day before, and of the spiritual and social revival he imagines his church fostering. He is seated at a lectern, wearing a dark suit and white shirt. He has close-cut hair, a slight moustache and soul patch, and a toothy smile. His laptop is open before him.

The day before, Rev. Palmer tells the crowd, the church hosted—along with Youth with a Mission, Healing Heart Ministries, Church of the Apostles, Holy Host, and Mercy Chefs—a 12-hour long service called Abode 12. The groups that partnered for this event represented a cross-section of Baltimore by class, race, and ethnicity. Palmer says he is bone tired, that he didn’t get home until 2 a.m., but that it was all worth it.

“It was a beautiful representation of what we should be,” Palmer says, of what the church should be, what the world should be. Yesterday, he points out, a man drove a car into a crowd of counter-demonstrators at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Yesterday, a crowd gathered just down the road outside M & T Bank Stadium, demanding the Baltimore Ravens pick up quarterback and activist Colin Kapernick.

But here, in this church, they were seeking a way forward, learning how to “love on each other,” a phrase he repeats often. Palmer claims, “It was good to be here and see a little bit of heaven.”

The congregants, young and old, black and white, nod and “Amen” in agreement. The small group of bleary-eyed worshippers seems to be, like Palmer, tired but inspired.

Set Goals

When Ryan Palmer left Baltimore for Denison with his father in August 1988, he wanted to put as much distance between himself and his home city as possible. He wanted, he says, to “expand his ‘range and vision.’”

Palmer grew up working class in Baltimore in a two-parent household with an older brother and a younger sister. He’s the middle kid—vivacious, gregarious, theatrical. Despite all this stability, he points out, “Baltimore has its share of challenges. This is where you get The Wire, Homicide, The Corner.”

There were temptations outside his door, but somehow, Palmer says, he stayed away from them. When the older kids would go off to smoke weed or to get into a fight, they’d say, “Nah, shorty. Go home. This is not for you.’ I never smoked weed or anything. They wouldn’t even offer it to me!” Palmer laughs. “They’d say, ‘You go study. Go hit the books.’”

And he did. He attended Baltimore City College High School, where he cultivated his stage presence but not a plan for college. He wasn’t sure he could go to or afford college—so he just didn’t apply. But during his senior year, while attending an after-party for a performance of The Wiz, he told Mrs. Gladden, the mother of another actor, that he had no college plans. She told him: “Monday morning, go to the counselor’s office, get an application, fill it out, and we will submit it together.”

Palmer’s guidance counselor was a woman he admired—she had gone to Oberlin and talked to him about “liberal arts” and what that meant. Like every other high school student, he found the concept a little elusive. The outgoing young man associated her communication skill with liberal arts, and that was all he needed: “I wanted to be able to have a conversation with anyone. I wanted those tools.” Two weeks before graduation, he learned he was accepted to Denison University in far-off Granville, Ohio.

Driving to college with his father, he was filled with excitement, ready to learn new things, meet new people, until he realized that his dad was lost.

They were heading too far south on I-95, and when they got back on course, they had to climb up through West Virginia. At some point, they stopped for gas. His father went into the station to pay. Ryan stayed outside to pump. “Some little kid, couldn’t have been 4 or 5,” Palmer remembers, “says, ‘Mommy,’ and before she could stop him, ‘there are niggers out here.’ And I turned around and said, ‘Where?’ I’d never been called one before, and then I realized, ‘Oh, you mean, me?’”

It was a moment of recognition on so many levels. After that incident, Palmer remembers, he grew quiet and processed the exchange all the way to Ohio. “I’d heard stories, but I’d never experienced it like that.”

At Denison, Palmer found himself in a new world. He grew up in a city and was now in a village. He grew up jaywalking and was now in a place where folks waited for the lights to change. He grew up around people of color and was now at a college where only 6 percent of the student population were students of color.

“Any time race became an issue in the classroom,” he says, “everybody turned to look at me. But that’s not surprising. ‘Perhaps Ryan is the first non-white person you’ve met.’ Plus, we were all trying to figure out who we were.”

In those first few months, he says, he was still trying to find his niche, to find his place on campus. He would go the whole day, he says, without seeing another person of color until he went to the cafeteria at dinner.

A friend once asked him the classic question, “Why do all the black people sit together in the cafeteria?” Palmer remembers responding, “We don’t. You all do, and we’re just left over.”

But God had a plan for him, he says, and some people helped force that plan into his sightlines. It happened, he says, through encounters he had in college.

The first encounter was with Shirley Chisolm, the first black woman elected to U.S. Congress and the first woman to run for president. She came to speak at Denison during his first semester. “During the Q and A, I asked her how she was able to be so successful going up against old-boy networks.” In Palmer’s opinion, you don’t get more “old boy” than Congress. “You know what she said was her key to success? She never went to a meeting not knowing what she wanted to accomplish.”

He also remembers her telling him, “I always let people know what it is that I want to get done. Then I say, ‘Now, either help me, or get out of my way!’”

This made an impact on a young Ryan Palmer, who wanted to make his own mark on the world. He wanted to accomplish his goals, he wanted to graduate from college and into a life of success.

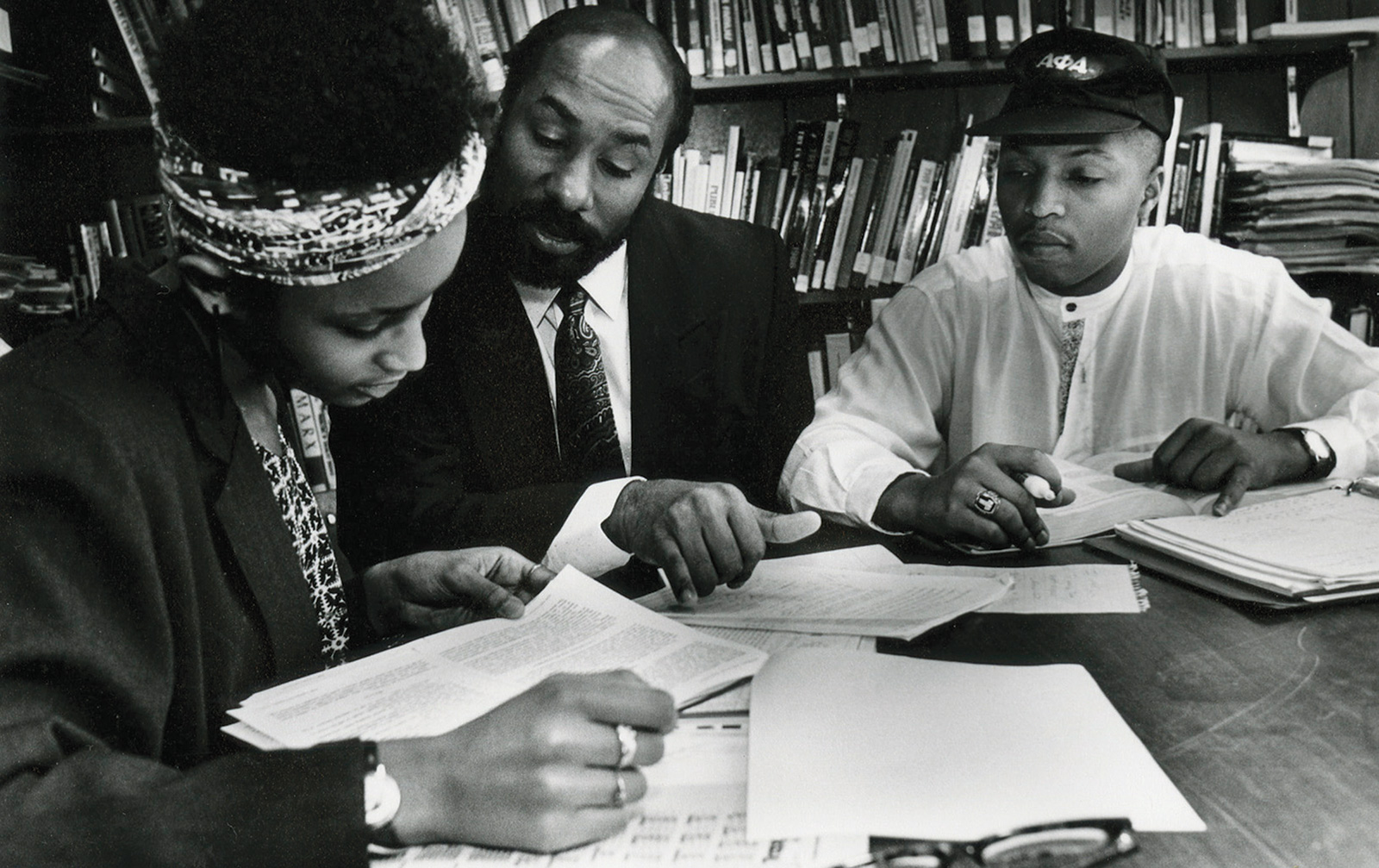

He remembers visiting speakers John Amos and Father Clemente, and professors like John Jackson and Gill Wright Miller ’74, people who came into his life early on, who helped round out his liberal arts education, mentored him, and gave him confidence.

Palmer remembers, too, the role his fraternity played in helping him find a community at Denison. He became an Alpha in 1990, the charter year for the group at Denison.

Palmer was struck by the group’s focus on supporting young black men and committing them to doing great things. He remembers sponsor John Gore telling Denison Alphas time and again, “If you’re going to do it, do it in excellence. If you’re not, don’t do it.”

This, Palmer says, is exemplified by the role of historically black fraternities at colleges around this country—a level of seriousness and an expectation to be involved in social justice work.

And as a theater and economics double major, Palmer says he wanted to be a complete person, “Left half, right half of my brain. Denison helped me piece those things together.”

Be Authentic

On March 21, 1998, just as he was finishing University of Maryland School of Law, he married Leslie Judge, and later that summer, he passed the bar exam. His dream was to move to Los Angeles to work in film, but Leslie wasn’t too keen on the idea. They compromised on New York City.

Palmer had his degree and was ready to go, but then his church suddenly needed a pastor and his name was mentioned. He says he didn’t want to become a pastor—that’s not the life he had in mind.

“So, I prayed and said, ‘If it’s your will, let there be 100 percent support.’”

The congregation was unanimous—they wanted him to step up. “So the very first sermon I preached came out of Jonah, Chapter 3, and the title was ‘Want and Willing.’ I didn’t want to do this, but if you’re a Christian and a true believer, it’s not about what you want, it’s about what you’re willing to do for God.”

Around this time, Leslie and Ryan began making frequent trips to hospital emergency rooms. Leslie was feeling strange, having trouble walking, feeling dizzy, not seeing well. Doctors began exploring possible causes for her symptoms—Lyme disease, ALS, other neurological ailments. Eventually she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Today, Leslie is legally blind and has been in a wheelchair for more than six years.

In the turmoil and pain of Leslie’s diagnosis, Palmer was surprised to find his memory accessing information he’d learned in an Experiential Anatomy class he took with Dr. Miller in college. Not only did he recall specific concepts regarding movement and issues of health, but also a larger sense of how to read the body and its responses with a more sophisticated understanding of it as a place for questioning and watching for answers.

Miller remembers him as an outgoing and extroverted student in class, but with an unexpected capacity to listen and take in information as if his life depended on it.

The combination of his religious faith and the reassurance that his acquired knowledge brought to bear has given Palmer the confidence to carry on through difficulties and fear. He also depends on his strong sense of who he is and what’s important to him. “You know, my goal in life is to be authentic, to be who I say I am. I’ve got to be that as a lawyer. I’ve got to be that as a pastor. I’ve got to be that as a husband. I’ve got to be that as a member of my community.”

Listen, Learn and Delight in the Future

A mile-and-a-half walk up North Avenue from his church is the heart of West Baltimore, where much of the unrest took place in late spring 2015 after Freddie Gray died from injuries suffered while being transported in a Baltimore Police van.

Palmer admits to being critical of those protestors in church the following Sunday. But then the next week he listened to conversations in his community. He paid attention. He re-evaluated.

“The next Sunday, I went to the pulpit and said, ‘I owe these kids an apology.’ My generation was taught there’s a right way to protest, and we followed the rules. But these kids did more in three days than we did in 30 years.”

He says that he didn’t understand them until he started listening to them. “I find, in a lot of situations, people are yelling or acting out because no one is hearing them.” Becoming aware of this, he says, has made him a better leader and a better citizen. This has been an important lesson for a man in his position.

Seventh Baptist Church, now Seventh Metro Church, was founded in 1845, and yet Ryan Palmer is only the church’s second African-American pastor. But the church and the community have transformed over the years, and he hopes to capitalize on that, to create a vibrant and modern multiethnic congregation.

He’s aware of the changes that are coming to this community. Maryland Institute College for Arts is across from the church and new families are moving in.

“The gentrification is going on. Some of it is admirable and desirable, but the bad part is the displacement that comes with it.”

His church has felt the pressure of possible displacement. Recently, an investor purchased a $6,000 water bill the church owed at a tax sale. The bill was the result of a burst pipe, and it was a significant hurdle for the small church. After a story in the Baltimore Sun, a donor stepped in to pay the bill.

The church has rebounded and is beginning a project, in conjunction with Gragg Cardona Partners. It is a redevelopment of a building the church owns across the street that will have 46 mixed-income rental units, office space, restaurants. The project will help ensure the church’s financial stability and, Palmer hopes, benefit the neighborhood and allow the church to expand its ministry and support community-based arts programming.

Palmer’s unbounded hope for the future is infectious. During a recent church service, he shared that with his congregation.

“We need to teach the word,” he says and pauses, “the word that God loves you no matter who you are.” This is important to remember, he says, especially in moments when you feel stuck, and you don’t know where to go next. “When I get stuck, I want to know where I am, how I got here, and what’s next.”

The text for the service (Jeremiah 29: 10-15) is a declaration appropriate for anyone who feels stuck. It reads in part, “For I know the plans I have for you … plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.” Palmer adds to the scripture, “Our purpose as a church is to bring joy to the city.”

In his church on a Sunday morning, Ryan Palmer, the artist, is directing a great performance. Not the service per se, but a life well lived. A vibrant and dynamic life.

He pauses after reading from Jeremiah and looks at his congregation with a big grin. “We are in the beginning stages,” Palmer declares, “of a mighty work.”

In some ways, in his own life, Ryan Palmer is in the midst of a mighty work.