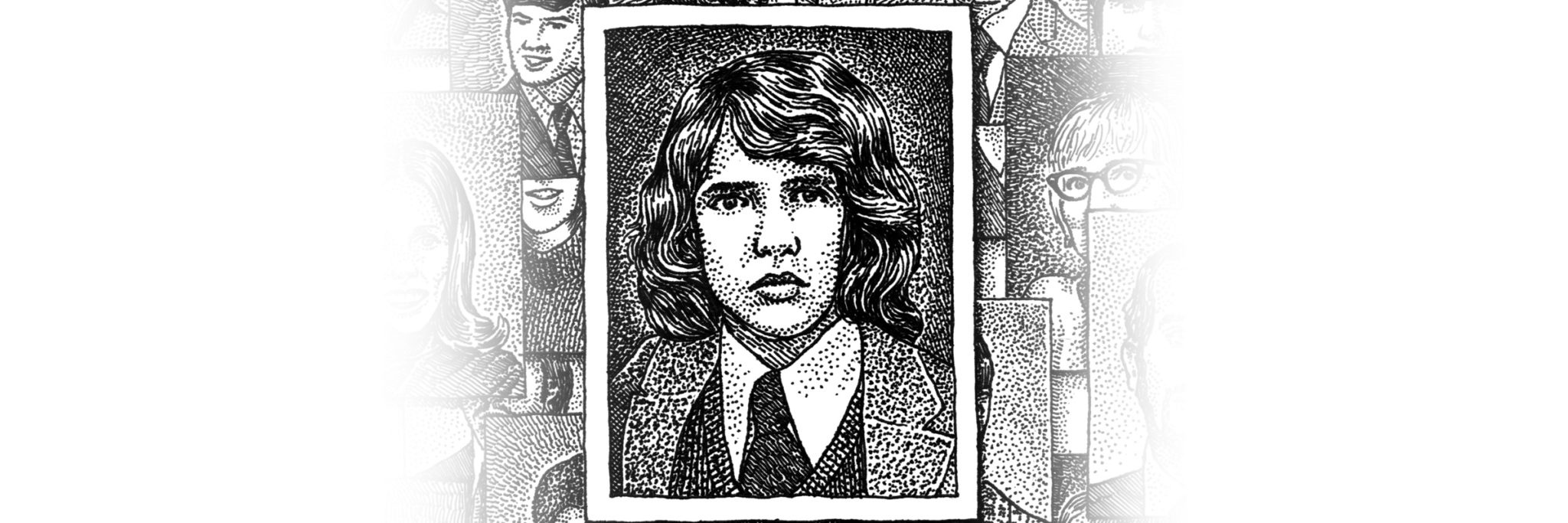

I was editor-in-chief of my high school yearbook in 1974—so get out. The yearbook was cool, the staff was cool, and we had the last word on how that year—our year—would look forever. Arriving at Denison a few months later, the idea of another yearbook felt like a poor fit with my new college identity, too much like the bellbottoms from high school. So I backed away slowly, deciding to let somebody else do it this time.

As penance for stiffing the Adytum in the 1970s, I agreed, 30 years later, to be its advisor. Mostly because I couldn’t say no to the acutely uncomfortable young woman, an Adytum staff of one, who begged me, without ever looking directly at me. By mid-semester it dawned on me that she wasn’t responding to my emails because she had, without mentioning it, quit.

We were 122 years into a robust and enduring Denison tradition, and it was me left holding the empty bag. Nice, Karma. I had to explain to anxious parents of graduating seniors that unfortunately there couldn’t be a yearbook if there weren’t students who wanted to make a yearbook, and for better or worse, no, my job didn’t include doing it for them.

Universities across the country have been reporting the decline and death of yearbooks in larger numbers every year, and archivists (for whom yearbooks are the Holy Grail) have reached to their listservs for answers. Blame is squarely aimed at social media, of course, for its easy and relentless fire-hosing of imagery and algorithmic nostalgia. Until 20 years ago, photos existed as singular physical objects, onto which you’d jot names and dates, then put them in albums or boxes, or share them in printed books.

When images replicate into infinity with a click, their number and ubiquity lead us to assume they’ll always be on hand when we reach for them. But where exactly will we reach, and where do the narratives live? Who in 10 or 100 years will be able to find this digitized material in one place and know who and what they’re looking at? The visual stories of our lives are getting buried daily in our feeds and inboxes. We think we know where they are, sort of, and we intend to get in there and organize them when life gets less crazy. But where would we even put them?

It’s worth asking if it matters. Not too much to college students raised on smartphones. We can all agree it isn’t a lack of enthusiasm for self-documenting—these are hardened professionals. The missing piece is that easy technology has diverted us from a manual system which is still a more dependable way to capture and contain images with information. Ironically, technology has made creating a book so much easier and less expensive.

The analog yearbook, stodgy as it is, will never require software or hardware updates to access: It’s on your shelf. You turn the pages, and you’re having a sensory experience that includes the knowledge that you’re holding the same book that your hands and eyes worked over years and years before.

Yearbooks are informational, and also experiential: They ignite nostalgia. Not a first-tier human need, but as forward-moving as we think our species is, we’re hardwired for the aimless longing we feel when we look at an old photo and suddenly feel time and our place in time pulled out from under us. We’re recognizing our mortality. And we’re wondering why anyone ever thought their hair should look like that.

Unlike me, Patrick Banner ’18 shared his high school yearbook skills and completed nearly three volumes of the Adytum single-handedly. He graduated last month leaving a gift to fellow students and to Denison. He also shepherded a small group of first-year acolytes from India, Nepal, and Buffalo, N.Y., to complete the 2018 book—we’ll soon see what college looks like through their eyes.