Last fall, Denison students flew from Columbus to London, looking for King Richard III. He’d been dead for more than 500 years, but the 2012 discovery of the monarch’s skeleton beneath a municipal parking lot in Leicester, England, challenged preconceived notions of Richard’s reputation as a malicious, murderous ruler who had proliferated for centuries.

Led by David Goodwin, associate professor of geosciences, and Fred Porcheddu ’87, associate professor and chair of English, the students in the Denison Seminar, “Looking for Richard III,” explored the life, death, and legacy of a person who may have been misunderstood.

“I thought it would be fun for students to be able to learn about isotypes in the same class in which we read about Josephine Tey,” says Goodwin, a paleontologist who came up with the idea for the course after renting the movie Richard III, starring Laurence Olivier. “There was an opportunity to combine the science that’s been done on Richard’s body with a more humanistic perspective of the man, through history and how he’s been viewed in literature.”

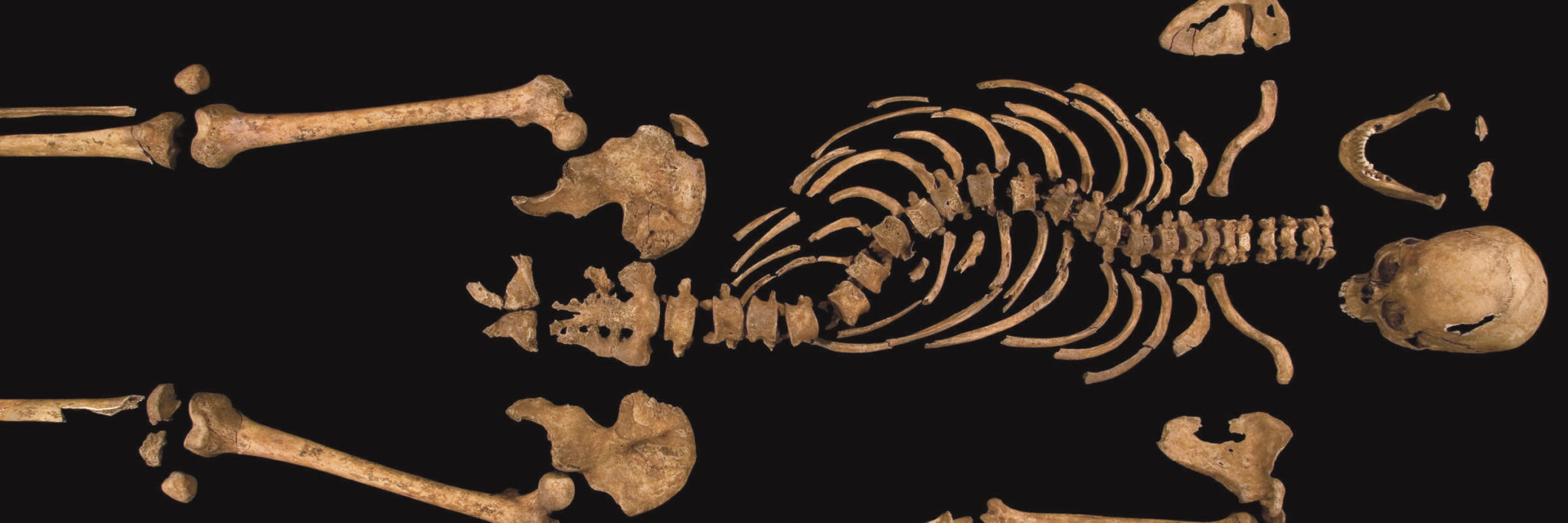

As part of the course, during their week-long trip to England, the students visited numerous locations, including Bosworth Field, the sight of Richard’s death, and Leicester Cathedral, where he was reburied in 2015. They also met with the lead archaeologist and forensic osteologist involved in the discovery and analysis of Richard’s body, which revealed some astonishing revelations about the infamous ruler, the man—and themselves.

For instance, Richard was described as a “hunchback” in William Shakespeare’s Tragedy of King Richard the Third. In reality, he was afflicted with severe scoliosis. It was also rumored, over hundreds of years, that he died a coward’s death while trying to flee the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, exclaiming, “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!” But he may have fallen from his horse and actually needed another to continue fighting.

“Who Richard was, in some ways, is unknowable,” Goodwin says. “Since the discovery of his body, we have learned things about his physicality. We have the body, the manifestation of the idea of Richard III. But that says nothing about the motivation of the man, or the decisions he made, or the context in which he made them.”

In looking for Richard III, students were asked to evaluate how much they know by asking what they don’t. “The most important realization in the course was ‘where does our sense of truth come from?’” Porcheddu says. “Our experiences tell us, it’s all shades of gray. Nobody is a complete monster, nobody is a complete hero. We must inform ourselves, but always remain willing to be convinced otherwise.”