It’s a brisk morning in late March of 2013, and Dale T. Knobel is pacing back and forth addressing a packed auditorium in Slayter Union. He comes to rest briefly in order to pull a piece of paper from his jacket pocket and read an excerpt from a letter dated 1906—a letter written by Howard Ferris, a judge on the Cincinnati Superior Court, to William Hannibal Johnson, a Denison professor of Latin who later would compile a brief history of the college’s presidents.

“I have but one son,” wrote Ferris, “and am anxious that he should make the most of his opportunities.

“I sent him to Granville because I believe in small colleges … where an aggregation of students, brought together from different parts of the country, congregate for similar purposes. I believe in a small place, peculiarly adapted for purposes of study … And I was therefore anxious that my boy should live in that atmosphere.”

“That’s Denison today,” Knobel tells the audience—the last group of prospective students he’ll ever meet as Denison’s president. Next year, Adam Weinberg, currently the CEO of World Learning in Brattleboro, Vt., will be standing here as Denison’s 20th president, addressing a bunch of high-schoolers and their parents. And Dale Knobel and his wife, Tina, will be settling into retirement.

Knobel spent the first 20-odd years of his academic career teaching history. And while his schedule forced him to give up lecturing soon after he came to Granville, he still looks like the archetypal college professor: tall, genial, silver-haired, eyes rimmed by wire glasses. He elicits laughter with wry remarks about the college application process, while simultaneously making what amounts to an earnest sales pitch on behalf of the institution he has served since 1998.

The presentation at Slayter is classic Knobel: using a letter about Denison that is more than half as old as the college itself to make a point about the enduring virtues of the institution today. This is, after all, a man who continues to self-identify as a professional historian, and who has made the history of the college a minor specialty—a way of satisfying his scholarly urges and of trying to understand the present through the lens of the past. “Nothing comes out of the ether,” Knobel says. “Everything has context.”

But missing is a crucial bit of context concerning the letter from Ferris to Johnson. The majority of students at the time (and for much of Denison’s history) were white, affluent, Christian, and male. While much of what Ferris had to say about the college still rings true, the “aggregation of students” to which he referred has changed a great deal.

It’s hardly unusual to hear reference to diversity and inclusion at a prospective student meet-and-greet. Those terms have become watchwords among administrators across the country—not to mention selling points for their institutions. But the progress that Denison has made toward those goals has advanced considerably during Knobel’s tenure.

In recent years, the number of students of color at the college has more than doubled, while the percentage of students receiving some form of financial aid has more than tripled.

Gary Baker, a professor of modern languages who came to Granville in 1989 and was chair of the faculty when Knobel arrived, recalls that student cars were once uniformly nicer than faculty ones. That is no longer the case now that one-sixth of all students are the first in their families to attend college, and nearly one-fifth receive federal Pell grants, which go to those with the highest documented level of financial need. There is an increasingly visible contingent of gay and lesbian students, and significantly more religious pluralism, as well. As a result, the Denison community is more varied now than it ever has been—a fact that is reflected in the proliferation of identity groups, from Students of Caribbean Ancestry to the Muslim Student Association.

Knobel is not solely responsible for this, but he did have a considerable hand in fostering it. He’s also quick to point out that having a diverse campus is one thing; learning to work and live and study within that newfound diversity is another.

One holiday season, my son Will and I were interested in walking through the Knobels’ house during the Candlelight Walking Tour. We stood in line on the sidewalk in front of Monomoy Place, waiting for our turn to enter. Once inside, we were warmly greeted by Dale and by piano music in the background. We walked a few feet and Tina spotted us. She shook our hands and was immediately drawn to Will, who was about 7 years old at the time. She led Will by the hand, told him how fond she was of bunnies, and asked him to look for all the rabbit statues and figurines as he walked through the house. To Will it was a fun game. To Tina, the rabbits were a remembrance of her son, Matthew, who had died in a car accident in 1992. I learned later about the significance of the rabbits and the importance of keeping memories of a lost child in the parents’ hearts and lives. My sister lost her 16-year-old daughter last year. I often think of the Knobels and their struggle, and I find it comforting to see their strength as they deal with the loss of their children. Sharing memories of a child is one of the best forms of comfort you can give to a parent who has experienced this type of profound loss. My time in Monomoy Place with Will is a special memory I will hold onto long after the Knobels have left Denison. —Susan Kosling, Production and Academic Administrative Assistant, Department of Dance

“I like to think that the signal achievement of my years here has been the creation of a more broadly representative student body,” says Knobel. He is sitting in his office on the second floor of Doane Administration Building, surrounded by shelf upon shelf of books—including those he has written or contributed to himself—ringing the room like scholarly ramparts.

It would be naive to assume that the intellectual preoccupations of any given college or university president directly influence his or her work as an administrator; that a physicist’s penchant for bosons or an English scholar’s obsession with Jane Austen would find expression in presidential priorities and policies. But Knobel has turned a lifelong fascination with the history of difference—how people define it, describe it, and react to it—into a central plank of his presidency.

Knobel attended high school in Hudson, Ohio, an outer-ring suburb of Cleveland that was founded by settlers from Massachusetts and Connecticut. His own people were steelworkers who traced their origins to England, Wales, Sweden, and Switzerland; his father, Harry, worked his way through Fenn College, the predecessor of Cleveland State University, before picking up an M.B.A. on the GI Bill and going to work for Standard Oil. Knobel learned his way around Ohio by accompanying his dad as he drove across the state on weekends, scouting service station locations. But the footsteps he followed in were those of an uncle, Robert Boehm.

Boehm taught history for 45 years at Defiance College and was, as Knobel recalls, a true military historian—the kind who participated in Civil War re-enactments and staged elaborate toy-soldier battles in his basement. “I spent my childhood seated on the floor with him, playing vast war games,” says Knobel, who still has a collection of toy soldiers at Monomoy Place. Some of that childhood also was spent prying musket balls out of trees and gathering artillery shells from the ground on the historic battlefields of West Virginia, where Boehm took Knobel on summer pilgrimages. “You dragged me to a few of those, too,” Tina Knobel reminded her husband over dinner at the Granville Inn one evening, with just a hint of comic exasperation—the same hint that crept in as she recalled the war games she sat through when the two were high-school sweethearts. “And I’ll drag you to some more once I retire!” he shot back, grinning.

And so it was with his sights set on a career as a historian that Dale Knobel first came to Denison as a student in the fall of 1967. He played soccer, made friends, liked his professors, but ultimately found the Denison of that era too familiar for his tastes, the student body too much like his peers back in Hudson: white, suburban, the sons and daughters of successful businessmen. So he left for Yale to complete his undergraduate work. “In a way, that foreshadowed my career, and my interest in diversity and representativeness,” he says.

As a doctoral candidate at Northwestern University, Knobel nurtured a continuing interest in the Civil War that had less to do with military engagements than with the shifting relationships between various racial and ethnic groups before and after the conflict. His mentor, the historian George M. Fredrickson, published a series of books that examined how perceptions of African-Americans had changed over time, including The Black Image in the White Mind, which traced the evolution of racial stereotypes from the first days of the Republic to the early 20th century. Knobel came to wonder whether perceptions of European immigrant groups might not have been similarly fluid. Fredrickson quipped that Knobel ought to write The Off-White Image in the White Mind, and he did: In Paddy and the Republic, Knobel used written descriptions of the Irish in America to analyze how stereotypes of a white immigrant group had changed over the course of the 19th century. Together, Fredrickson and Knobel wrote an essay on the history of discrimination against minorities in the United States, and Knobel went on to write a second book, America for the Americans, that used the history of anti-immigrant sentiment to get at American attitudes toward assorted ethnic, racial, and religious groups from the 18th century to the 20th.

Much of what Knobel has written about stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination remains true today. Nonetheless, a predilection for mulling the ways in which groups of people perceive and label each other might not seem directly germane to the work of a college president, a creature who is typically judged by his or her ability to court donors and expand facilities. But Knobel returned to Denison at a propitious time for a man with his background and interests.

In 1995, the Denison board of trustees and Knobel’s predecessor, Michele Myers, made the decision to revoke the residential privileges enjoyed by fraternities, which had dominated campus social life for generations. It was a controversial move that did not sit well with many alumni, but it was also an important gambit toward making Denison a more welcoming place for a less homogeneous student body. As Knobel and other administrators are fond of saying, much of the learning that goes on at a residential college takes place beyond the classroom, in the interactions that occur in the residences and dining halls, on the playing fields and the quads. By that logic, the broader the range of student perspectives, the richer the educational experience ought to be. They also emphasize that an independent liberal arts college like Denison must expand its applicant pool and recruit a wider array of students from historically underrepresented populations if it is to remain viable. Yet despite having made significant strides in that direction by the late 1990s, the college still had a long way to go. The year after Knobel transferred to Yale, the Denison administration pledged to enroll 100 African-American students; when he returned 30 years later, it had yet to do so. Toni King, associate provost and professor of black studies and women’s studies, recalls that when she arrived in 1997, many in the Denison community were looking for a new president who would continue to open up the campus monoculture.

Knobel often is asked whether he misses teaching, and his reply is always the same: He doesn’t miss it because he does it all the time. The only difference is that most of that teaching now takes the form of advocacy—advocacy on behalf of students and faculty, and for the direction in which he believes the college should be going. And much of that advocacy has been for increasing diversity in all its forms.

“As a historian, he talks about all of these things in theory,” says Baker. “But when he got here in ’98, he started putting that theory into practice on this campus.”

College presidents are many things to many people. On the one hand, says provost Bradley Bateman, who himself will take the reins as president of Randolph College in July, they personify the institutions that they serve. As such, a president functions not only as a prime fundraiser and salesperson-in-chief (witness Knobel’s appearance at Slayter), but also as a living seal of approval, whose very presence is the institution made flesh. This, says Bateman, is why people tend to light up when the president enters a room—something they are less inclined to do when the provost, who is responsible for the curriculum and the faculty, walks through the door.

This is also why presidents and their spouses are such public figures. Watching the Knobels attempting to leave the Granville Inn after a quiet dinner, one has to wonder how much privacy they have had over the past decade and a half. The trip from their table to the front door took nearly half an hour, as they were flagged down by an endless parade of college staff, townspeople, and alumni. Tina, who serves on the boards of several local organizations and has overseen the ongoing rehabilitation of Monomoy, talks about how difficult it will be to leave Granville, and admits that it is “a little frightening” to contemplate life in retirement. But one does not get the impression that she will entirely miss having always to be “on” in an environment where she and her husband are always in the public eye—even in their own front yard at Monomoy Place, which sits in the heart of Granville and is owned by the college. This may have been especially difficult for the Knobels given their personal history; in 2011, their daughter, Allison, died after a seven-year battle with breast cancer, a tragedy that inevitably became part of their public narrative. (Their son, Matthew, was killed in a car accident many years earlier.) The upcoming move to Georgetown, Texas, where Knobel was once provost of Southwestern University, has much to do with the couple’s desire to be closer to Allison’s two children—their grandsons—who live in Houston.

But college presidents are more than allegorical figures and local celebrities; they are also chief executives who hold real power inside their institutions. And Knobel has attempted to use that power to make Denison more broadly representative and accessible.

According to senior administrators, it was Knobel who decided that Denison should partner with the Posse Foundation to recruit cohorts of inner-city students; Knobel who hired Bateman in part to diversify the faculty, a task Bateman previously had undertaken at Grinnell College; and Knobel who replaced the plaque at the main college entrance that read “Denison University: A Christian College of Liberal Arts”—a phrase that had become inaccurate with Dension’s independent status decades earlier—with one that reads “Denison, a College of Liberal Arts.” Likewise, it was Knobel who asked the admissions office to adopt a “test optional” policy under which applicants would no longer be required to submit SAT or ACT scores, resulting in steady growth in applications from students of color and first-generation college attendees; and Knobel who led the charge to increase the funds that Denison invests in financial aid, extending access to students who would not otherwise have been in a position even to consider attending the college. In Toni King’s view, changes like these have a multiplier effect: By making the student body more diverse, they attract a broader range of applicants, which makes the student body even more diverse, and so on in an ongoing circle of diversification.

Yet everything has a price—even something that is generally viewed as an absolute good. As the college continues to absorb more students from a larger number of distinct groups, faculty must learn to cope with a broader range of sensitivities and styles of engagement, while administrators must work out how best to serve a more complex set of needs. Do gay and lesbian students, for example, require special health and counseling services? Do homeless students need a place to stay over summer break? “We have to teach differently, advise differently, think differently,” says King.

There is also a risk that, rather than mingling in productive ways, some in that varied mix will prefer to stick with students with similar backgrounds, leading to a kind of Balkanization of the campus. Knobel is well acquainted with this sort of thing—much of his scholarly research deals with the Balkanization of America—and it is partly what he means when he talks about the difference between representational diversity, which the college has largely achieved, and engaged diversity, which takes a lot more work.

At the same time, the intimate nature of life on the Hill forces students to interact with people the likes of which they may never have encountered before, and whom they may not necessarily have even wished to encounter; while each fall brings with it the arrival of 600 first-year students bearing not only a fresh batch of hopes and dreams,

but also their own prejudices and preconceptions. These factors aggravate what Laurel Kennedy, vice president for student development, calls “the discomfort of difference”—a discomfort that doubtless contributed to the tensions of 2007, when a series of racist and homophobic incidents led students, faculty, and staff to hold an emotional daylong forum. There are ways of encouraging an increasingly disparate population of students to communicate across the boundaries that might separate them, and of helping them build a shared sense of community on campus. In 2011, for example, the college established “Listening for a Change,” a program that fosters small-group discussions among students, faculty, and staff. But there is no silver bullet. “Cultural change,” says Bateman, “is slow.”

In all likelihood, Denison would have had to make this transition, with all its concomitant benefits and challenges, at some point. By making it a priority, however, Knobel essentially gave the institution a jump on the future—and the opportunity to manage in an intentional way a transformation that otherwise could have been even more difficult and disruptive.

“Many colleges are grappling with these things,” says King. “They are not necessarily as far along as we are, because we’ve had Dale Knobel. We leapt forward.”

Dale and Tina have been incomparable ambassadors for Denison in Licking County and in numerous higher education settings, not to mention right here on campus, where they both have engendered warm good will and collegiality among all those who work, teach, and learn in this special place. —Tom Hoaglin ’71, Chair of the Board

I was getting gas in Granville, and President Knobel was at the adjacent pump. We exchanged greetings, and then he proceeded to ask me about my summer research. My roommates and I all agree that it is a wonderful thing to have a president who is not only friendly (he said hello!), but considerate (he knew my name!). Knobel certainly made great contributions to Denison’s academics and administration, but his geniality is what has set him apart, and it is what I will miss most of all.—Tori Newman ’15, a religion major from Willard, Ohio

Dale Knobel supported activities and events sponsored by the Granville Historical Society. The year 2005 served as the bicentennial year of the coming of the New England settlers from Granville, Mass., to their new home near the Welsh Hills of Ohio. The Granville Historical Society undertook the writing and publication of a three-volume bicentennial history of the village, Granville, Ohio: A Study in Continuity and Change. Dale assisted in finding funding for this project and additionally wrote the introductory chapter to Volume One. He helped rescue from oblivion the imprint of “The Denison University Press.”

—Anthony Lisska, Maria Theresa Barney Professor of Philosophy

In the many speeches Dale has given, he always has emphasized the importance of empathy. In psychology, there is much discussion on the relationship between resilience and empathy, the latter being a key component of fostering sincere, strong, healthy relationships, which in turn contribute to the protective processes that make us more resilient to the adversities of life. I’ve been contemplating that connection and remembering moments with Dale during which I felt emotionally elevated by his empathy. Memories such as Dale’s visit to my office to welcome me during my first year as an assistant professor of German. Memories of Dale practicing the pronunciation of Akademischer Austauschdienst for the Awards Convocation. Memories of Dale’s patient answer to yet another passionate email from me about an innovative idea based on technology that would change the future of the college. His response: “That is not who we are.” (But even so, he listened.) Perhaps my favorite moment with Dale was when I experienced a professional crisis, one that manifested feelings of uncertainty and a desire for flight. After talking with Dale, I felt restored. He helped me find my balance again. —Gabriele Dillmann, Associate Professor of German

There is also a risk that, rather than mingling in productive ways, some in that varied mix will prefer to stick with students with similar backgrounds, leading to a kind of Balkanization of the campus. Knobel is well acquainted with this sort of thing—much of his scholarly research deals with the Balkanization of America—and it is partly what he means when he talks about the difference between representational diversity, which the college has largely achieved, and engaged diversity, which takes a lot more work.

At the same time, the intimate nature of life on the Hill forces students to interact with people the likes of which they may never have encountered before, and whom they may not necessarily have even wished to encounter; while each fall brings with it the arrival of 600 first-year students bearing not only a fresh batch of hopes and dreams,

but also their own prejudices and preconceptions. These factors aggravate what Laurel Kennedy, vice president for student development, calls “the discomfort of difference”—a discomfort that doubtless contributed to the tensions of 2007, when a series of racist and homophobic incidents led students, faculty, and staff to hold an emotional daylong forum. There are ways of encouraging an increasingly disparate population of students to communicate across the boundaries that might separate them, and of helping them build a shared sense of community on campus. In 2011, for example, the college established “Listening for a Change,” a program that fosters small-group discussions among students, faculty, and staff. But there is no silver bullet. “Cultural change,” says Bateman, “is slow.”

In all likelihood, Denison would have had to make this transition, with all its concomitant benefits and challenges, at some point. By making it a priority, however, Knobel essentially gave the institution a jump on the future—and the opportunity to manage in an intentional way a transformation that otherwise could have been even more difficult and disruptive.

“Many colleges are grappling with these things,” says King. “They are not necessarily as far along as we are, because we’ve had Dale Knobel. We leapt forward.”

The Power of Posse

Established in 1989, the Posse Foundation sends multicultural teams, or posses, of 10 urban public high-school students to colleges and universities across the country on full, merit-based scholarships—an idea that first occurred to Deborah Bial, founder of the Posse Foundation, when a student told her that he would never have dropped out of college if he’d had his posse with him. Under Dale Knobel’s leadership, Denison became a charter affiliate of the Foundation’s Chicago office, and accepted its first Chicago Posse in 2001. In 2005, the college hosted its first Boston Posse, becoming one of only a handful of schools to accept Posses from more than one city. (Today, 16 of 44 participating institutions do so.) As Bial said in 2010, “Dale Knobel is part of a network of selective college leaders who believe this is important, so he’s making it happen.”

There are now some 80 Posse Scholars on the Hill at any given time, a presence that Laurel Kennedy, vice president of student development, credits with having jump-started a demographic shift on campus. The program also generates a ripple effect as participants tell their friends back home about Denison, further broadening the college’s applicant pool.

The practical benefits of Posse go both ways: Scholars gain access to a college they might not otherwise have had the means or the inclination to attend, while Denison gets a steady infusion of highly qualified students from diverse backgrounds who might have eluded the traditional recruitment and admissions process.

But Posse confers other, less tangible benefits on the college as well. Because Posse candidates are nominated by high schools and community-based organizations on the basis of both academic and leadership potential, they tend to play an outsized role on campus, founding or leading student organizations and sharing their perspectives in ways that enrich the educational experience for all students, both in and out of class.

And while the cohort-based system was designed to increase retention among participants by providing a built-in support group, the presence of Posse Scholars also helps attract and retain other students from underrepresented groups. That kind of knock-on effect has made Posse an important lever for changing the campus culture—one with impact that may be far greater than the numbers alone suggest.

Green is the New Big Red

When a group of students asked Dale Knobel to sign the American College and University Presidents’ Climate Commitment in 2007, he declined—not because he liked burning coal, but because he felt that the college wasn’t ready to sign an agreement that would require setting a target date for becoming carbon neutral, and taking concrete steps to make it happen.

With Knobel’s prodding, however, that changed. Denison now has a Campus Sustainability Committee, a campus sustainability coordinator, and a comprehensive sustainability plan that commits Denison to achieving carbon neutrality by 2030. (Knobel signed the commitment in 2010.)

In the last four years alone, Denison has undertaken four major building

renovation projects in accordance with the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) standards prom-ulgated by the U.S. Green Building Council. It has established the $1 million Green Hill Fund to finance energy and water conservation projects, such as last year’s upgrades to campus lighting and heating systems. (The fund is part of a nationwide Billion Dollar Green Challenge.) And the college has built a community garden, financed by the Environmental Venture Fund at Denison, founded by John R. Hunting ’54, to enable faculty and students to grow their own produce.

Such initiatives not only save the college resources and money over the long term, says Sustainability Coordinator Jeremy King ’97, they also serve an educational purpose, giving students the opportunity to learn about pressing global issues and to develop valuable skills in an informal and often hands-on way. Right now, for example, students are building a new, super-efficient cabin at the Homestead, the ecologically sustainable alternative community just north of campus.

“How often does a liberal arts student do construction work,” asks King, “let alone green construction work?”

Brick by Brick

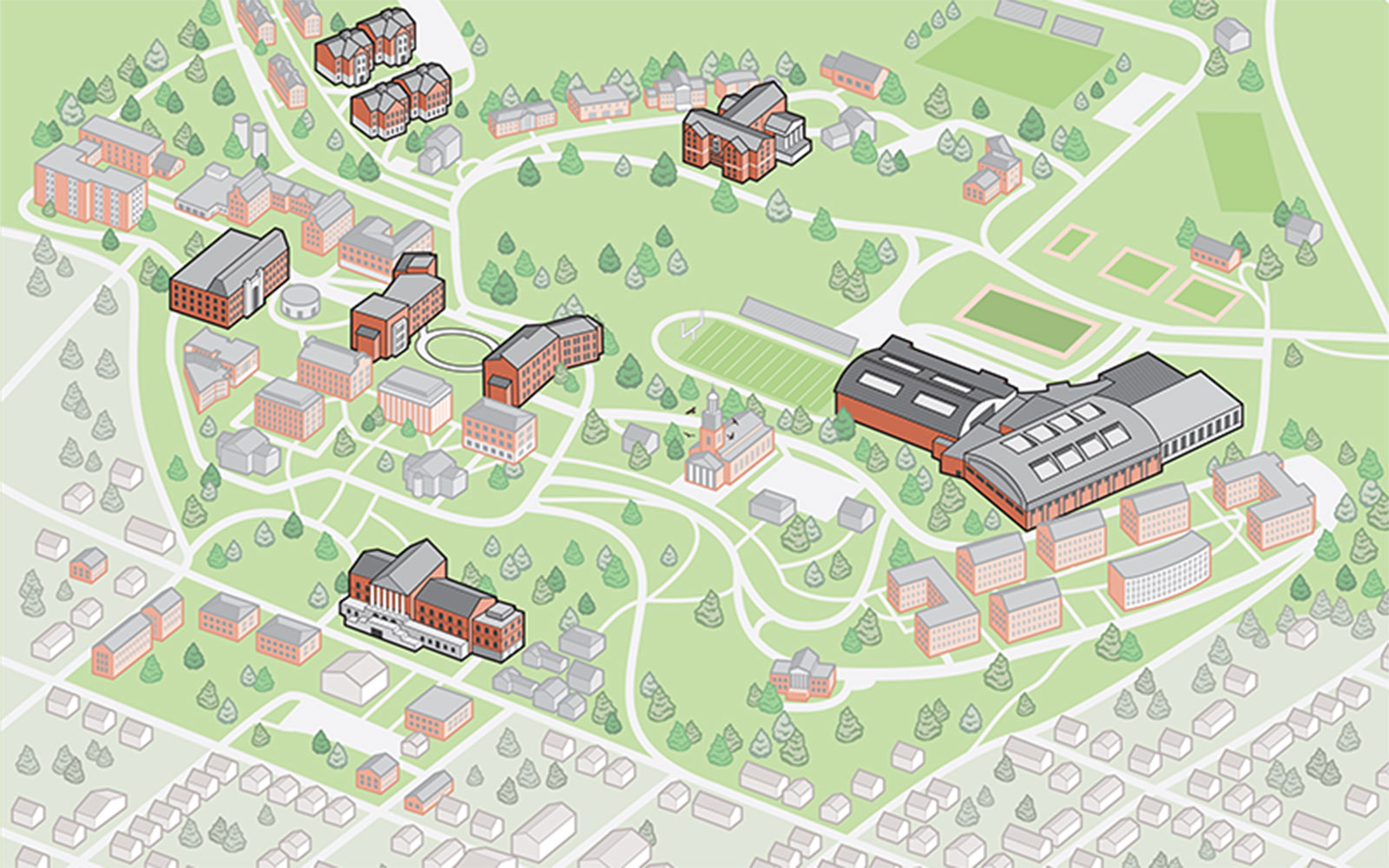

He promised he wouldn’t be a “building president,” but when he arrived back in 1998 and saw the need for updated facilities—from science labs to art studios to student housing—it became a promise Knobel couldn’t help but break. But not everything was brand-spanking new. Throughout the years, he led renovations to existing facilities like Slayter Student Union, Stone Hall, Fellows, Higley, and Mulberry House, and he led renovations and expansions of campus icons like Deeds Field and Piper Stadium. But some building projects changed the face of campus. Here’s a look at just a few of the campus buildings that have been born or undergone a major makeover in the last 15 years.

The Brownstones and Good Hall

For years student housing was the same old, same old: two to a room; concrete cinder block walls; bathrooms off the hallway for the residents to share. But in the late ’90s, new apartment buildings started to rise on campus, beginning with the Sunsets. In 2001, under the Knobel administration, Sunset D (now called Good Hall) made an appearance, and the entire Sunset block was equipped with kitchens. Even so, the “Sunnies” weren’t enough to meet demand, so the Brownstones were built as well. Seniors now can live four to an apartment, where they can eat in their own kitchen and watch TV in their own living room. And with two bathrooms per apartment, students only have to deal with one roommate’s inability to change the toilet paper roll.

Ebaugh Laboratories

When the Ebaugh renovation and expansion project wrapped up in 2012, the building was more than 19,000 square feet bigger and boasted new classrooms, as well as teaching and research labs. In keeping with a commitment made by the college in 2008, it was built to meet the U.S. Green Building Council’s Leadership in Energy and Design (LEED) and earned a gold rating. For those who remember the Ebaugh of the ’60s (it was originally constructed in 1966), there are a few visible remnants from the original building, including an old staircase that went untouched, a lab stool dating back to the ’20s, and a safe once used to store chemicals.

Reese-Shackelford Common

The Common, which sits on top of the parking garage, rose out of what the students of the time called the “Slayter crater,” after construction crews tore up the ground behind the student union to create what has become a meeting place since its completion in 2003. Parents say goodbye to their first-year students here after Induction ceremonies; alumni dine and dance here during Reunion Weekends; and during the year, you’re sure to spot random yoga classes and Frisbee players.

Chamberlin Lodge

Chamberlin Lodge has roots in the Greek system, having once been the Phi Gamma Delta House. These days it’s a five-story apartment building with 13,000 more square feet than it had when it originally was constructed back in 1927. The new Chamberlin opened its doors to students last summer.

Samson Talbot Hall

Named for Denison’s fifth president, Samson Talbot Hall of Biological Science sprung up in 2003. In the 19th century, it was Talbot who ushered in a modern science curriculum at Denison, so it made sense to put his name on a building that would enhance and expand the laboratory and classroom space available to students and faculty. All of the spaces throughout Talbot are “smart,” meaning that technology plays a big role in the classrooms and research going on in there. There also are six teaching labs where students conduct experiments in everything from rearranging genes to modeling ecosystems.

Burton D. Morgan Center

Dedicated in 2003, Burton Morgan is something of a campus favorite, especially when students want a comfy couch or a quiet corner to study. It houses a variety of techno-rich classrooms and several campus offices, like Career Exploration & Development, Alumni Relations, the Burton D. Morgan Program in Liberal Arts and Entrepreneurship Education, Organizational Studies, and the Vail Series. There’s also a busy social gathering room, with windows overlooking the Welsh Hills. That room was just renamed Knobel Hall.

The Mitchell Center

The Mitchell Center is still the Mitchell Center of 1994, but now it’s bigger and better. Last summer, construction crews filled in the old pool and made way for one of the center’s main features, the Trumbull Aquatics Center, which includes an Olympic-size pool and diving well that juts off an extension of the original building. This summer, the new Crown Fitness Center will be completed in time for the students’ arrival come fall. And there are lots of cool spots throughout the building for faculty, staff, and students to get some exercise or for student athletes to train.

The Bryant Arts Center

What was once Cleveland Hall (the men’s gymnasium back in the early 1900s, a student union in the ’40s, and later a fine arts building), is today the Bryant Arts Center, which houses studios and classrooms, as well as gallery space. The fourth floor holds senior studios, which give studio art majors their own personal creative space. The building was constructed with the environment in mind, and much of the material was recycled from the old building or bought locally. The main piece of art hanging in the front lobby actually is recycled, too. The paint-splattered gym floor from the building’s former life now hangs in sections on the wall, welcoming students, faculty, and visitors.

In the many speeches Dale has given, he has always emphasized the importance of empathy. In psychology, there is much discussion on the relationship between resilience and empathy, the latter being a key component of fostering sincere, strong, healthy relationships, which in turn contribute to the protective processes that make us more resilient to the adversities of life. I’ve been contemplating that connection and remembering moments with Dale during which I felt emotionally elevated by his empathy. Memories such as Dale’s visit to my office to welcome me during my first year as an assistant professor of German. Memories of Dale practicing the pronunciation of Akademischer Austauschdienst for the Awards Convocation. Memories of Dale’s patient answer to yet another passionate email from me about an innovative idea based on technology that would change the future of the college. His response: “That is not who we are.” (But even so, he listened.) Perhaps my favorite moment with Dale was when I experienced a professional crisis, one that manifested feelings of uncertainty and a desire for flight. After talking with Dale, I felt restored. He helped me find my balance again.

Gabriele Dillmann, associate professor of German

Making Monomoy Home

The first time Tina Knobel walked through the front door of Monomoy Place—or “the big house,” as her grandsons call it—she was struck, as are many, by its sheer size. But something else about the massive Italianate Victorian manor and its dark wood interior struck her as well: “It needed life, and it needed light.” As it happened, plans already had been put in place with the help of Nancy Brickman ’54 and her decorator from Chicago, to lighten the paint scheme and draw up a fresh palette of colors derived from the artifacts and beautiful oriental rugs already in the house. The extensive wood paneling and trim, which had been given a preliminary restoration in 1980, were painted in several rooms to reflect the generous natural light from Monomoy’s many windows. The rooms on the main floor were furnished, and paintings from Denison’s museum were hung to welcome the Knobels when they arrived from Texas in 1998.

The house has had a long and varied history since it was built by Dr. Alfred Follett in 1863 and named for a peninsula off the coast of Cape Cod. At the turn of the century, the structure was expanded by Follett’s son-in-law, John S. Jones, who expanded the roof to accommodate a third-floor ballroom. Denison acquired Monomoy Place (which is celebrating its 150th anniversary this year) from the Jones estate in 1935, to serve as temporary housing for freshmen women. It continued to function as student housing into the mid-1970s, when it was in such poor condition that the university made plans to demolish it. President Bob Good and his wife, Nancy, recognized its unique value and saved it from the wrecking ball, renovating it to serve as a presidential residence. The Goods moved into Monomoy in 1980.

For the Knobels, living in an old house for the first time has been an education. Tina has taken a particular interest in learning about the Victorian period and has incorporated those sensibilities into personal touches she has added to Monomoy’s public spaces. A whimsical cabinet she found for the dining room, hand-painted with rabbits, bows, and butterflies, feels like the right fanciful touch in an elegant room of mahogany, silver, and chinoiserie wallpaper. Her grandmother’s wingback chair is tucked into a nook of the grand staircase, surrounded by her collections of rabbits and family photographs, bringing warmth and intimacy to the monumental scale of the house.

“You feel like a detective in a house of this vintage,” says Tina, who discovered in a dark drawer an old wick trimmer and brass tray, which belonged to Denison’s first president, John Pratt. She had it polished and placed it on the mantel in Dale’s ground-floor study, where other favorite historic objects of Dale’s are on display. One of Tina’s most satisfying projects was finding an artisan to reproduce the frosted glass pattern that remained in only one of the transom panels of the front door. The craftsman expanded that floral pattern to the sidelights and the large single pane of the front door, bringing a period touch as well as privacy to the main entrance.

Leaving Monomoy Place will not be easy. It has been Dale and Tina’s home longer than any other house they’ve lived in, and its halls and grounds hold many memories. It’s the place where they’ve cooked, slept, and watched TV for 15 years, and its second floor has been their sanctuary in a house that serves so many public functions.

Tina’s exacting hand and discriminating eye will leave a lasting legacy of her years as caretaker, and she takes comfort in the thought that she has had a role in preserving Monomoy for future generations—and in helping others appreciate the great house that stands on Broadway.