One day in early June, shaded by a wind-rattled ponderosa, Dr. Jade Wimberley ’92 lifts the arm of a boy with nervous eyes. She wraps two canvas flaps around his bicep, squeezes a pump several times, and lets her meter hiss and deflate. “Are you afraid of the dark?” she asks quietly, “or of lightning?” No, says the boy; he likes storms. What was it, then, that made him call for the guides? He had been on his “solo,” a student’s rite of pas- sage before graduating from Open Sky Wilderness Therapy, and he had done well until left alone. Even though the guides were close, he became lonely. “At home, didn’t you spend time by yourself in your room?” Wimberley asks him. Yes, but that was different, he says. He had his phone and could text his friends. “When you first got here you’d hardly look at us,” says Wimberley. “I see a lot of life coming back.” She brushes her fingers across a flaking callus on his foot. “Your old layers are coming off. The old Jeffrey.”

The week had been difficult for Jeffrey* and the other adolescent boys in Team Avatar. Several had vomited— an unwashed hand at dinner the likely culprit—and four new students had joined the group. One of the boys, determined to leave as soon as he arrived, faked stomach pain, and a guide took him to the hospital. The doctors found nothing wrong. On the ride home, the boy said he had given up; he wouldn’t try again. “Everything we do here has therapeutic value,” the guide tells me. “Every piece of their life is carefully considered and managed.”

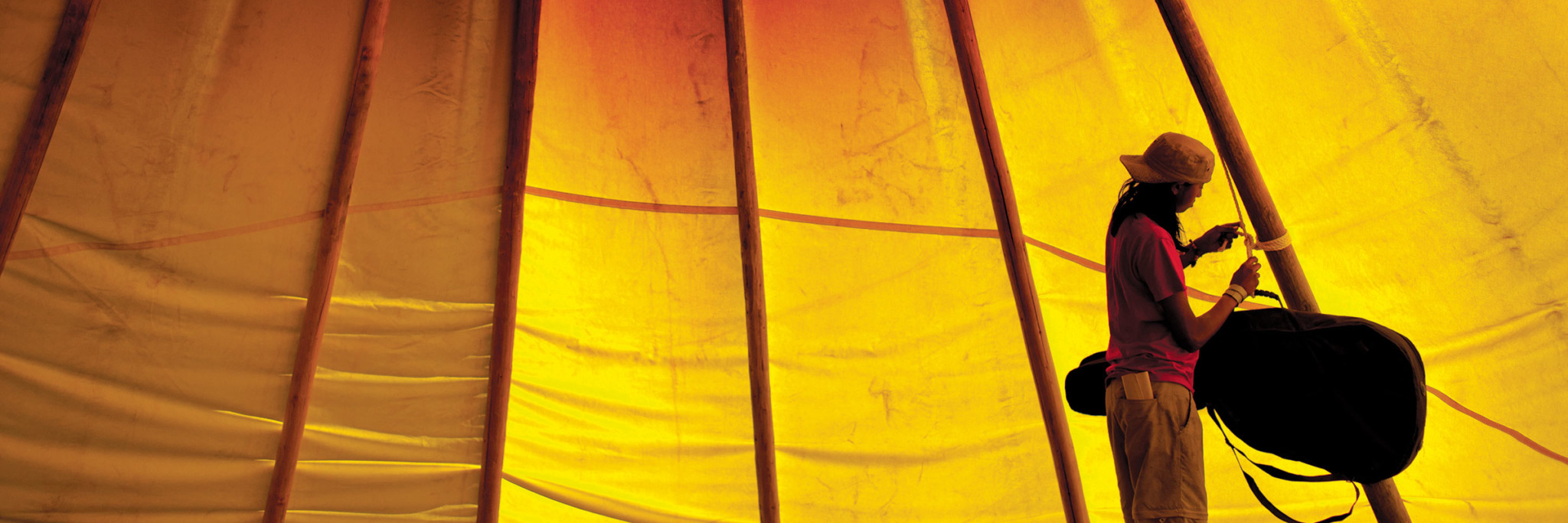

In a remote pine forest in southwestern Colorado, just west of the La Plata Mountains, “management” means something very different from setting curfews or locking the liquor cabinet. Students in the program operate out of a base camp, where teams live in tipis, cook their own food, collect water, and build fires. Several days a week, they venture off accompanied by guides to hike and explore the Rockies. During these expeditions, students practice meditation and meet with therapists using the natural world as a backdrop for self-reflection. There are rules: Students may speak to one another only within earshot of their guides. They must ask permission to go to the bathroom, fetch belongings from the tipi, or handle knives to cook dinner or carve spoons. For every emotion, they have a process to express it. Everything they take into the field, down to their underwear, comes from the program warehouse. If a student threatens to hurt himself or run away, a guide won’t leave his side. And any question is fair: Is he sad? Has he slept? When did he last defecate? Why did he eat one helping, not two?

Fernandes’ philosophy on wilderness therapy stems from one simple idea: Place the student in a challenging, supportive environment where issues can rise to the surface. Then, attend to the person’s mental, physical, and spiritual health. That’s where Jade Wimberley comes in. A friend of Kettle, Wimberley started at Open Sky in 2006. Not long before, she had quit her marketing job and attended a naturopathic medical school in Arizona. When she moved to southwestern Colorado in 2004, she opened a private practice. “I was seeing twenty patients a week, running a natural food store, and meanwhile Nicola was asking me to work part time in the field. So one day I did, and I fell in love with the boys in Team Avatar.”

Fernandes drives me to Open Sky’s 3,000- acre base camp on a windy day in June and parks beside a sunny, open meadow. He stuffs sandwiches and a water bottle into his canvas pack and checks his phone. It’s his busiest week of the year. Kids are home for the summer and getting into more trouble than usual. Parents call every day, sometimes as late as 10 p.m. “We’re crisis oriented,” he says. “We work with families when that last straw happens.”

We set out across the field and duck into the forest. Fernandes points to the meditation tent, plastic tarps pulled taut across a pipe frame and strung with prayer flags, where students gather on Tuesday mornings after returning from expeditions. When we come to Team Avatar, one student is strumming a guitar; another is reading, his back against a tree. Wimberley sits with a dark-eyed boy from Queens, no more than 16, who had arrived that weekend and speaks with an eerie sense of calm, as if sedated by his own shock. Later, the boy tells me that two men had woken him at 4 a.m. in a psychiatric hospital and taken him to the airport, where they bought him breakfast. “Apparently, I told them I like pancakes,” he says, “but I don’t even remember.” The boy has been depressed for many years. When he started smoking pot and trying harder drugs, his parents said he was self-medicating. “I’m not a wilderness person,” he tells me. “I’m terrified of spiders. But I’m not my regular self here. I just pick them up and throw them.”

“You’ve heard of the big burly men that come in the night, right?” Fernandes asks me. More than half the students at Open Sky arrive via “transport service.” “It’s rare there’s any need for physical altercation,” Fernandes says. “It’s an emotional time. When communication between the parents and the kid is already a mess, it’s the best option for getting a student here safely.” Sometimes parents deliver students themselves, but it doesn’t always go well. “The kid apologizes, saying everything will be different. They manipulate the situation. Parents are very vulnerable to their children’s emotional pleas.”

Wimberley, or Dr. Jade, as the students call her, is a slight, blond woman with athletic shoulders and a sweet face that turns ruddy in the sun. She admits to struggling with anxiety herself but doesn’t show it. In her forties, she’s quiet and thoughtful and maintains a hip sort of confidence that her students can relate to. When she’s worried about a student, she has trouble sleeping. Earlier in the day, she was called on to examine a student writhing from abdominal pain, but his vitals—aside from a slightly elevated heart rate—appeared fine. Wimberley suspected he was faking and told a guide to keep a close watch. She wasn’t ready to take him to the hospital, but she would consult another doctor later that night.

“It’s really scary sometimes,” she says. “If I make a wrong call, we’ll get critics saying, ‘It’s boot camp. The kid was writhing in pain and was denied medical care.’”

That evening, Wimberley and I visit an adults’ group called Team Evergreen. Eight men between the ages of 19 and 28 gather around a fire with their guides, Jessie and Billy. Jessie, who served in the Air Force, has baked a cake and iced it with dried apricots simmered in Sucanat. A student named Nick scoops rice, beans, and sausage into bowls, topping each with a forkful of vegetables. He douses his in hot sauce and eats as he explains to me the value of meditation. “There’s a saying that goes, ‘Those with depression live in the past. Those with anxiety live in the future.’”

“That’s what’s so great about it,” adds a student named Sam, who has folded the wide brim of his sun hat to resemble a baseball cap. “Like, are you going to sit here and wonder how long you have to do this for? Or are you going to stay in the present?”

Having finished with our first helping, we line our bowls in front of Nick, who divides the leftovers among them, overlooking Billy’s by accident.

“That’s another thing we do,” a student tells me. “Say you want to bring up something serious with a person, you say, ‘Do you want to bust an ‘I Feel?’ It’s called reflective listening. You say what you’re feeling and why, and the person repeats it back to you.”

“I’ll give an example,” says Nick. “I feel bad when I skip Billy’s bowl on the beans. Sorry, Billy. I feel that way because you didn’t deserve it. I was spacing out.”

“You feel bad when you skip my bowl,” says Billy, looking at Nick. “Don’t worry, man. We’ve still got cake.”

After sunset, Sam reads us a letter he has written to his mother. It isn’t finished, and he isn’t even sure if he should send it. He hasn’t heard from her and doesn’t know where she is. The last he knew, she had sold the house and moved to California. In the letter, Sam reminds her of the champagne bottles she finished before lunch and of the times he found her unconscious on the floor. Once, when he was 15 and she was out of alcohol, Sam says, she made him drive her to a restaurant where she threw a fit after the waitress refused to serve her. When Sam went into rehab last year, she stayed only one night for family weekend, drank a bottle of wine, and went home.

Sam finishes reading and stares at the fire. After a long while, Jessie asks how he is feeling. “Better,” he says. “I just want her to know these things.”

“It seems like you’re blaming her for a lot,” says a student. “I mean, she still loves you. You should give her a little gratitude. You have some good memories of her too, right?”

“That’s the thing,” says Sam. “When she’s sober, she’s the sweetest, most loving woman in the world. But when she’s drunk, she says the meanest things anyone’s ever said to me. And the way she shows her love is by buying me things.”

“Some parents don’t know how to show it any other way,” says the student.

“Sam,” says Jessie, “what do you hope to get out of sending this letter?”

“To make her understand [how] she’s affected me.”

“Remember when we talked about resentment as our number-one offender?” says Wimberley. “What if you took all that pain you carry with you and worked on it therapeutically? Find that compassion for your mom and for yourself.”

Sam closes his notebook and pulls his knees close. His voice has been steady, but now it cracks. That’s why he wrote the letter, he says. He’d feel relieved, and she’d have to hear him out. She can’t argue with feelings.

“But alcoholics will try,” says Wimberley. “She’s not going to take responsibility, but you can. Isn’t that why you came here?”

“I knew if I didn’t do something I would end up dead, in jail, or on the street.” Sam looks up at Jessie and says, “Why is it that whenever it’s my turn it always ends up so intense?”

“That’s a good thing,” she says. “It means you’re working the important stuff out.”

“Compared to the hell I was living in before, this is a piece of cake.” Sam holds out his hands, and the others follow. They lift their palms to the sky and flip them over as if pressing the air into the earth. “Aho,” they say together, and then, laughing, “Blue skies and butterflies. No rain, no snow, no UTI’s.”

“It makes more sense when there are girls in the group,” says Nick.

That night, Jessie sings the boys to sleep.

Sam never thought he would remember his twenty-first birthday. He was riding in the van back to base camp, oldies blaring, the guys singing so loudly they had to crack the windows. Only five weeks before that, he had woken up in a hotel room with an infection spreading in his arm. It had been two years since he failed out of community college and started shooting heroin. His father gave him a job, but Sam lasted only five months. Soon after, his mother kicked him out for stealing. “I was just going from house to house,” he says, “living in hotels, barely scraping by, lying, cheating, stealing any way I could.”

From the hotel room, Sam had called his father, who checked him into a detox center and agreed to send him to Open Sky. “That first week, the thought of walking my twenty didn’t leave my mind,” he says. An adult student who wants to leave the program must follow a guide to the office in Mancos—20 miles away—where he’s allowed one call to his parents. If his parents refuse to bring him home, he can walk back to base camp or be dropped off at a homeless shelter. “It gives you a pretty good incentive to want to stay.”

One morning at meditation, the leader, Norman, asked the group to imagine the people they loved first happy and then sad. Sam began to cry. Norman asked what had happened. When he thought of his parents, said Sam, the sadness overwhelmed him. Norman asked Sam to close his eyes, and for several minutes, he led him in a breathing exercise. “When I opened them, I had this huge sense of relief,” says Sam. “I couldn’t remember the last time I felt that way. Norman and I—we just had this connection.”

Not all of the students have hit a bottom as low as Sam’s, nor do they understand so clearly why they have come to Open Sky. But it seems, at least, that they have learned to speak a language that conveys their serious thoughts as well as it conveys their jokes and jargon that only these eight young men will ever understand. It worries them to feel so comfortable in a situation soon to change. Three of the boys, including Nick, will graduate next week. “These exact moments will never happen again,” says Billy one day, as if warning them against chasing old highs.

That same afternoon, Wimberley approaches Nick, who is writing in his journal. “Did you want to talk to me about sobriety?” he asks. Nick has decided he will keep smoking pot when he leaves Open Sky but will stay away from other drugs. “I just really like weed,” he says. But Wimberley has just come to say hello. She has heard he will go to a new organization for aftercare. Most students who leave Open Sky ease back into the outside world through another program—a therapeutic boarding school or intentional living house—recommended by their family’s education consultant.

“Do you know it?” asks Nick.

“Yeah,” she says. “It’s nice, but it’s not the tightest of places. I mean, it’s right in the middle of a city.” Wimberley studies a necklace Nick has fashioned out of string and tabs he has collected from bread bags. “You’re funny,” she says, laughing.

“This?” says Nick, looking down at his chest. “It’s my wilder-bling.”

One morning at meditation, the leader, Norman, asked the group to imagine the people they loved first happy and then sad. Sam began to cry. Norman asked what had happened. When he thought of his parents, said Sam, the sadness overwhelmed him. Norman asked Sam to close his eyes, and for several minutes, he led him in a breathing exercise. “When I opened them, I had this huge sense of relief,” says Sam. “I couldn’t remember the last time I felt that way. Norman and I—we just had this connection.”

Not all of the students have hit a bottom as low as Sam’s, nor do they understand so clearly why they have come to Open Sky. But it seems, at least, that they have learned to speak a language that conveys their serious thoughts as well as it conveys their jokes and jargon that only these eight young men will ever understand. It worries them to feel so comfortable in a situation soon to change. Three of the boys, including Nick, will graduate next week. “These exact moments will never happen again,” says Billy one day, as if warning them against chasing old highs.

That same afternoon, Wimberley approaches Nick, who is writing in his journal. “Did you want to talk to me about sobriety?” he asks. Nick has decided he will keep smoking pot when he leaves Open Sky but will stay away from other drugs. “I just really like weed,” he says. But Wimberley has just come to say hello. She has heard he will go to a new organization for aftercare. Most students who leave Open Sky ease back into the outside world through another program—a therapeutic boarding school or intentional living house—recommended by their family’s education consultant.

“Do you know it?” asks Nick.

“Yeah,” she says. “It’s nice, but it’s not the tightest of places. I mean, it’s right in the middle of a city.” Wimberley studies a necklace Nick has fashioned out of string and tabs he has collected from bread bags. “You’re funny,” she says, laughing.

“This?” says Nick, looking down at his chest. “It’s my wilder-bling.”

Later that day, Fernandes and Wimberley talk about Nick’s next steps. “He’s a really good kid,” says Wimberley. “I think he’s going to be all right.”

“It’s very Western to assume the answers are in a pill,” says Wimberley. In theory, there’s little difference between handing a kid a Prozac or a capsule of St. John’s wort. Medication is important to keep her patients safe and stable, but overmedication can mask a person’s problems to such a degree that it’s hard to tell what’s really going on. Over time, Wimberley has relied less on herbal supplements and more on nutrition and mindfulness, practices that, if turned to habit, can give kids a sense of self-worth and control. “Nature can heal on so many levels that a pill can’t,” she says.

Wimberley remembers one boy who, on his fourth day at Open Sky, had tried to run away. As he approached graduation, he told her he was scared to leave. The woods seemed safer than his home, where he and his friends had gotten addicted to narcotics. “I actually feel emotions again,” he had said. “I’m excited for oats in the morning and peanut-butter-and-jelly for lunch.”’

“You’ve done so well,” said Wimberley.

“I think so too,” he told her. “Last week when I was hiking, I came to a cliff and got this urge to jump off. But I looked around, and there were these birds flying and aspens shimmering, and I realized that if I dove off the edge, I’d never get to see the whole world.”

Jade Wimberley, Naturopathic Doctor from The Health Revolution

Sierra Crane-Murdoch is a freelance writer based in Colorado. She is a frequent contributor to High Country News, a magazine that covers the American West.