This was a tough year for a lot of private colleges in terms of “making their class.” How have we fared so far?

A we received applications from 5,000 students–the third-most in Denison’s history. So in terms of the actual selection process, it wasn’t as difficult as in the past, even when we sought smaller classes, had a better economy, and were in a position to accept fewer candidates. But that said, in terms of enrolling the class, this has been the most challenging year of my career. You can’t separate college decisions from the realities of the economy. They’re closely linked.

The other thing that made this year exceptional, in terms of its challenge, is that we sought a larger number of enrollment deposits–not because we’re expanding our student body, but because we anticipated that the economy might hinder some students (both continuing and first-year students) from attending come fall, and we need to be ready for this contingency. This year we aimed for 650 enrollments by the end of May. Aiming for that many, in this economic environment, is really tough.

Explain the difference between deposited class and enrolled class.

Deposited class is the Office of Admissions’ goal for the number of students who have indicated their intention to enroll at the beginning of the summer. Enrolled class is the actual number of students who show up when school begins in the fall.

Why is there such a difference between those two numbers?

A lot of it comes down to “summer melt”–the process whereby students who have put down enrollment deposits at a college or university in the spring subsequently elect to withdraw their enrollment and enroll in another college or take some other step in their lives. Most of our summer melt is a function of wait list activity at other colleges that might be even more selective than Denison, but it might also include students whose families have had a change in their financial circumstances, and they decide that what looked good in April doesn’t look as good or, perhaps, not possible, by July when the first bill arrives. And then you always have some fallout of students for a variety of personal reasons: buyer’s remorse, distance from home, girlfriend/boyfriend problems. There are any number of reasons why students will elect to withdraw their enrollment.

How have we weathered summer melt so far?

This year that first spike in summer melt cost us 20 students. But we’re still holding at 654.

How have this year’s melt numbers compared to years past?

Two out of the last three years, we’ve lost 25 students between the early part of May and the early part of September. Then last year, we saw summer melt rise above that level. Most folks suggest that pop in summer melt nationwide was a function of some of the first elements of the economic recession beginning to take hold. Last year, many colleges and universities, particularly in the mid-Atlantic and northeast, had banked on their yield rates being similar to previous years, so they accepted the same number of candidates. When the increased summer melt occurred, they came up short on their classes, and they were forced to go to their wait lists, pretty deep in some cases. We lost a couple of students last year even as late as the last week of July.

You might wonder why we didn’t go to our wait list then. As it happened, we had such a strong base of enrollment deposits at that point that we actually had about 50 more students than we needed. So our class melted nicely, and we handily met our enrollment target.

This year, though, we went to our wait list early. Why?

You have a couple of choices when it comes to your wait list. You can go to the list before May 1 with the notion that accepted candidates have not yet decided what school they really want to attend, and you want to build a cushion. Or, you can wait until after May 1, and count your actual deposits to see whether or not you are short. One of the risks you run if you wait until after the first of May is that students may have settled somewhere else, and they begin to divorce themselves psychologically from Denison, even though they may have indicated at some point that we were their first choice college.

In the last week and a half of this year’s campaign, we were running between 15 to 20 students behind where we needed to be. I was concerned that our yields (acceptance-to-enrollment ratio) were lagging in the difficult economy. We had gone into the year projecting that our yield rates would fall between three and four percentage points from the previous year–that’s why we accepted about 400 more candidates than last year. As it turned out, our yield rate was lagging about four to five percentage points behind, so we decided that rather than wait until May 1, we would selectively go to our wait list.

Some would argue that by going to our wait list, we’ve lowered our standards in order to combat the economy.

First, understand that we haven’t gone to our wait list in more than three years, so we normally don’t use it. Second, you intelligently use a wait list to support your enrollment goals and that is what we did this year. That said, if you’re purely interested in the academic metrics of this class compared with the last three in terms of its classroom performance, board scores, and in terms of any number of objective academic measurements, the profile of the Class of 2013 is equal to, and in some cases better than the last three. Beyond that, one shouldn’t assume that because a student is placed on the wait list that their academic profile isn’t as good as another student’s. There may be other reasons why we put a student on a wait list–they may be very competitive academically, but because we felt they wouldn’t enroll or because they didn’t bring some particular talent or characteristic in which we’re interested, or some other textural quality to the class, we wait list them.

You and the rest of the admissions staff have to walk a thin line: You’re looking for a specific student, yet you want a diverse student body. Have you managed to create the perfect class?

I keep seeking the perfect class, but it’s probably never going to happen. There’s always one thing people can point to or criticize about the makeup of any class. We’ll hear people say, “Well, you didn’t have enough students of color or there weren’t enough science students, or there weren’t enough out-of-state students.”

There are some private schools that have yet to make their numbers. What did we do differently?

I think one of the features that sets Denison apart from some of our independent competitors would be–and this is not to be crass, it’s just a matter of fact–our financial strength. It has allowed us to do some things that our competitors have not been able to do in terms of pricing strategy and in terms of the product we’re promoting. Admissions staffers have little control over the product in terms of curriculum, faculty, facilities, or student life activities. We can’t do much about the place–it’s a lovely place, it’s got great curb appeal. Denison has fantastic faculty members, a strong academic program, and a great all-around experience, but it’s not necessarily right for every 17- and 18-year-old. However, our relatively strong financial position has allowed us to keep Denison affordable for more families from across the socio-economic classes.

We’ve also been in a position to compete for and hire some very talented faculty in recent years because of our financial strength. Keep in mind that some private colleges around the country have built their academic reputations– their national reputations–on the backs of faculty that were hired in the early ’60s. That generation of faculty, for the most part, has retired over the last 15 years or is in the process of retiring. Schools that are financially strong are able to recruit, hire, and retain similar faculty. Those schools that are not as financially strong, won’t be able to do that, and eventually those losses will slowly erode their reputational position.

Our financial status in years past has also allowed us to enhance campus facilities with the Mitchell Center, Higley Hall (the former Life Sciences Building), the Samson Talbot Hall of Biological Sciences, the Burton D. Morgan Center, several apartment-style housing facilities, and the soon-to-be-completed Bryant Arts Center at Cleveland Hall.

What does it mean for colleges that don’t make their number?

There are generally three revenue sources for colleges or universities. First would be the revenue you receive from student tuition and fees. Second would be the earnings on your endowment–for us, that’s about 30 percent of the budget. And the third would be gifts to the college. If you don’t make your first-year enrollment target, that immediately starts to have an impact on your revenue stream. So how are you going to make that up? Are you going to make it up with gifts in the advancement area? Maybe, but probably not, especially in this economy. Schools won’t mess with endowment earnings unless they start to get into real trouble. Colleges set a percentage of what they want to draw from their endowment and generally don’t want to increase that percentage, but sometimes they’re forced to, and sometimes they’re forced to get into the corpus in order to balance the red ink. So when you’re heavily tuition-driven, enrollment is very critical.

How much has Denison’s price tag, at just over $45,000 a year, affected our prospective students?

We’re talking about financial aid a lot these days. We have to. Nationally, in private higher education, we’re approaching a point where one year of room, board, tuition, and fees will represent the average income of a family in America. So right there, that kind of causes you to gasp. Right now, if we asked a student who is entering Denison to pay the full room, board, tuition, and fees, by the time they graduate–assuming a general six percent tuition increase on an annual basis–a Denison education would cost about a quarter million dollars.

So we spent a lot of time this year being proactive, asking families not to check Denison off because of the sticker price. Asking them to file for financial aid, and then determine whether or not they can afford us. Until families have all those answers they shouldn’t let the gross price scare them off. What they really need to be focused on is net price–what is their out-of-pocket cost going to be?

It can happen where a private institution is going to be equal in terms of cost, or in some cases, be less expensive than a public school. But if you’re in an independent college setting, your goal from a financial assistance standpoint is not to match the cost of a public-supported institution. Generally you’re not going to be able to do that. The hope is that you can at least close that gap a little bit, and that’s when the value of the experience comes in–the value that differentiates a small, personalized environment from a large, impersonal one. You hope that causes a family to say, “We’re going to sacrifice a little more, stretch a little bit more financially, to make this opportunity available for our daughter or son.” We don’t try to compete on a price basis with Miami of Ohio–it’s a fine place, a very worthy competitor, but we try to at least get in range where families can say, “Yeah, Denison is worth an additional $5,000 or $10,000. We understand why it costs more, and our son or daughter is a better match with the Denison environment.”

Liberal arts colleges have been taking a lot of hits lately, when landing a job is becoming more and more difficult. How does your staff sell a liberal arts education?

Our college is not in the business of training someone for a specific job. We are, however, in the business of educating students with a set of life skills that have always been important in the real world. We also speak to the adaptability of a liberal arts education. Career development officers will tell you that the average person will make seven to eight job changes in a lifetime, so adaptability is critical to our graduates’ success. Our curriculum certainly is one thing we can pitch to students, but it is a hard sell for some. No question about it.

There’s a comfort level associated with seeing a major that has a “career title” attached to it–business, accounting, journalism. People feel more comfortable saying, “I’m going to go into business,” than they do saying, “I’m going to be an English major.” Sometimes the response to the latter is, “What are you going to do with a degree in English?” Well, you could be a teacher, but you could also be an attorney or an accountant or go into medicine. One of our challenges early on is to communicate with our families and try to explain the career connection with the liberal arts and the marketplace because folks certainly want to know about the return on their investment.

What does the future of admissions look like for private colleges like Denison?

I’ll offer this data to show you what we’re facing. Last year, Denison’s average SAT for first-year students was about 1300. The College Board would tell you that only three percent of students who sat for the SAT a year ago came from families who reported an income of $100,000 and had an SAT of 1200 and above. There are 3,500 colleges and universities in the country. About 1,500 of those are private, so when you’re talking about those who can afford a higher-priced college like Denison and those who have the academic profile that you want as defined by, say SAT, you’re talking about a very, very small number of students available to you. Everyone wants those kinds of kids.

In the last two decades, higher education is second only to health care in terms of price increases. Consider the national resources going toward curbing health care increases in our country, yet the same kind of national attention has yet to be focused on higher education. It’s getting there–we’re hearing and reading more about the subject of future access to higher education, but it’s just beginning. On top of these challenges, some of the methods families have customarily used to pay for a child’s college education have evaporated as a result of the circumstances surrounding our national economy. So this phenomenon will also have an impact on private higher education in the near and long term. So we have eliminated an even greater percentage of the population who may have been able to consider Denison or another independent college 12 months ago but no longer can without significant financial assistance.

There are cartoon turkey vultures in all of the windows of Beth Eden House, home of the Admissions Office. What’s the story there?

In my business, in the month of April, just about anywhere you go, people greet you by saying: “How are the numbers?” Then they’ll say, “Hi.” Placing signs in the windows was a way of letting the community know that we made our target class. We used to just put up smiley faces, and then a couple of years ago, someone came up with the vultures, and we, of course, have an affection for the vultures at Denison since they started showing up on campus about 20 years ago. There’s still one smiley face that my staff created. It hangs in my office window, and it even has a mustache, minus the beard.

Block by Block

Robinson can’t do it alone–Here’s a look at the steps that go into recruiting a class, and the people who make the final decisions.

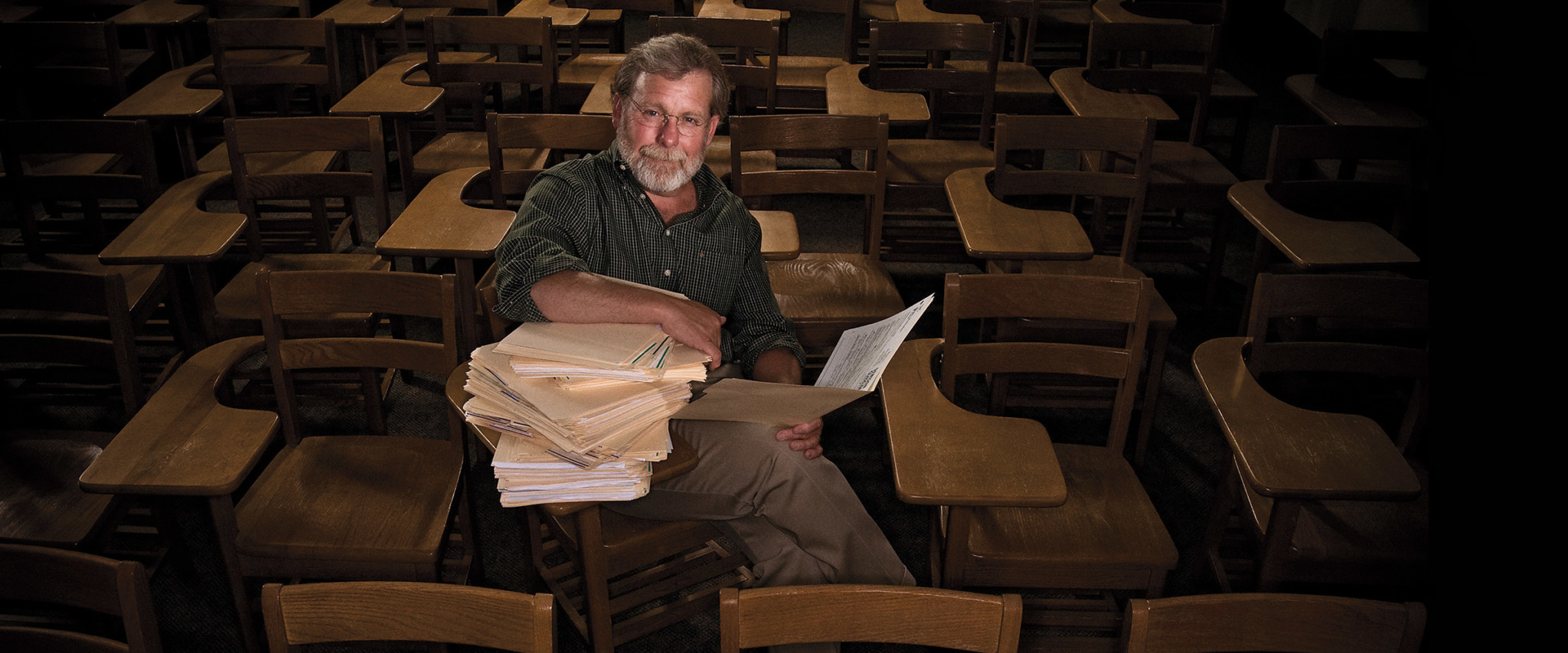

Perry Robinson can’t recruit students from around the world, read thousands of applications, give tours to prospective students, and interview the thousands more who want to sit down with admissions, so he employs a big team. There are counselors who cover territories across the country, visiting high schools, giving presentations, conducting on- and off-site interviews. There’s Nancy Gibson, who’s in charge of multicultural recruitment, and Sarah Leavell, who’s in charge of international recruiting. Then there are the graduates out there, the DARTers (Denison’s Alumni Recruitment Team led by admissions staffer, Mike Hills), who visit with students, cover college fairs, and pass around a good word for the Hill.

It’s a lot of work, and it takes time. The campaign to build the Class of 2013, for example, started all the way back in the fall of 2006, when the could-be Denison students were just beginning their sophomore year of high school. At the start of a recruitment campaign, admissions staffers head out looking for students who would make a good fit for Denison. Sometimes they meet them in high school presentations; sometimes high school counselors pass on a name or two; and sometimes they get to know them through their general applications.

Once those applications start rolling in, the admissions team really gets to work. They complete each prospective student’s file by requesting transcripts, letters of recomendation, and SAT/ACT scores (though submitting these scores is optional at Denison). Then, admissions counselors sit down and start reading. In any given year, they sift through nearly 5,000 applications and conduct 2,000 interviews. Only then can the team start deliberating.

So the big question: What, exactly, are they looking for? First and foremost, says Gibson, a student must be strong academically. Did the candidate challenge herself intellectually in high school? Did he get involved in his community through leadership roles or volunteer work? Or does she have some other talent beyond test scores and transcripts that would round out the class? “About one third of our decision is left to non-measurable areas,” says Robinson, “and as we move up the ladder of selectivity, those areas become more and more important in terms of sculpting the class.” By March, acceptance letters go out, and admissions counselors hope their top choices will say, “Yes.” But they don’t have a ton of time for wishful thinking–they need to start recruiting the next first-year class.