Exposure No. 1

Exposure No. 1

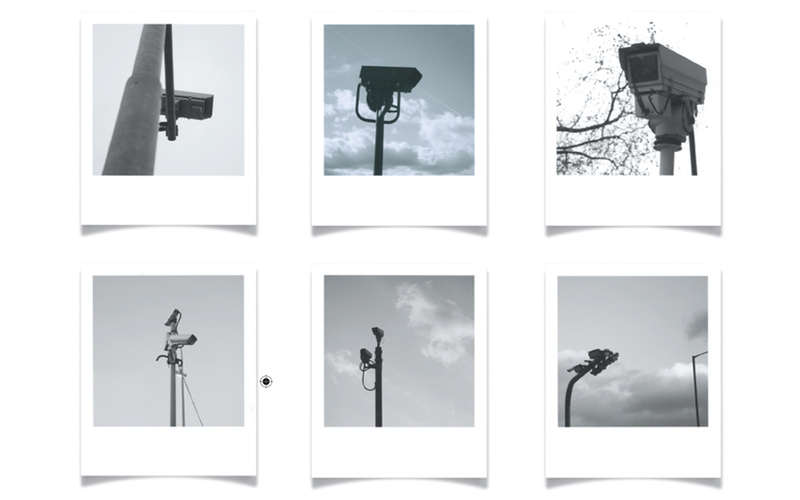

Smile: We're all on camera, and Mad Mohre is watching us being watched. The growing culture of surveillance has been Mohre’s absorbing interest since a 2007 semester studying printmaking at Goldsmiths College in London. She became aware of a closed-circuit camera mounted within view of her window, and grew increasingly curious as she saw another—and then another—on her walks through the city. Since the IRA terrorist bombings of the 1980s, London has become riddled with these weatherproof, pigeon-proof, bullet-proof snoops mounted high above the average citizen’s level of awareness. One estimate indicates that the average Londoner will be filmed by more than 300 cameras on more than 30 separate closed-circuit television systems in a single day.

What are the consequences, or the benefits, to a population under surveillance? Conversations with locals and serious research during her time in England led to an increasingly complex view of what might easily have become a critical diatribe on an overzealous domestic spying program. Mohre is clear about this: “I’m on the skeptical side, but not the cynical side.” The yin and yang of protection vs. personal rights has become a rich source for Mohre’s artistic expression, and culminated in her senior BFA thesis and exhibition this past spring, Watching (out for) You, in Denison Museum. An installation piece, “Sit Back, Relax,” incorporates a table setting of teacups patterned with security cameras on a linen cloth painstakingly embroidered with a map of Britain. It alludes to the intrusion of surveillance into the quintessentially British private sphere, and also to the level of normalcy and safety felt by many who know they’re being watched. A large wall canvas, “Focus,” appears to be a painting of the Union Jack with a pair of superimposed hands positioned to hold binoculars. On closer observation, the pattern of the flag is made up of many layers of textured, printed color and inscribed handwriting, implying the exposure of privacy as its many surface layers are peeled away.

Mohre acknowledges that video surveillance can help in prosecuting crimes, and that the self-monitoring of citizens who know they’re being watched can be a powerful deterrent. But she questions the idea of society choosing technological fixes from a place of fear. “The equipment doesn’t solve the problem—we need to think about broader ideas of social change to prevent antisocial behavior."

— James G. Hale ’78

Exposure No. 2

Exposure No. 2

It’s not the work that bothers Sean Leugers. That he can handle, and at least he knows what to expect…for the most part. But what has really worn on him for the six months that he’s been in Iraq is the driving that comes before and after work—the hours and hours of driving, often through dark and unfamiliar streets, sometimes through blinding sandstorms, sometimes out in the middle of nowhere, or other times under the uncertain gaze of hopefully-harmless pedestrians. And while worrying about deadly roadside bombs is one thing, trying to see them through darkness or sandstorms or sleep-deprived eyes is entirely another.

Nevertheless, there’s a lot of work to be done, and for Leugers and the 60 Marine combat engineers under his command, that means dismantling U.S. facilities built at the start of Operation Iraqi Freedom, repairing canal bridges, building huts—lots and lots of them—for Iraqi police, mitigating old chemical plants, and sweeping enemy weapons caches. They do most of it with rifles slung over their backs and caution on their minds—after all, it is Iraq, where “it seems everything can and will happen.” And they do all of it with Marine courage, skill, and diligence, and with the end goal of arriving home safely.

For Leugers, the end goal comes this September, when he’s due to return to Pataskala, Ohio, and the embrace of his wife, Kathryn Hoy Leugers ’02, a psychology resident who works in a group private practice. He’ll relax for a bit—go on a vacation, drive his Mustang, take in a Reds game or a movie, and soak in the sight of trees and grass. Then he’ll look for a new house and a job, maybe as a martial arts instructor or back in the finance industry, where he was once an internal wholesaler. And looking back on Iraq, he’ll try to set aside thoughts of corpses and cesspools and burning garbage, of bombs and snipers and close calls, of the pockets of evil that seem to wait around each corner. But he’ll never forget the loyalty and honor of his comrades, nor the desert’s mystifying ability to make him reflect on life—and death—in this world.

— Paul Pegher

Exposure No. 3

Exposure No. 3

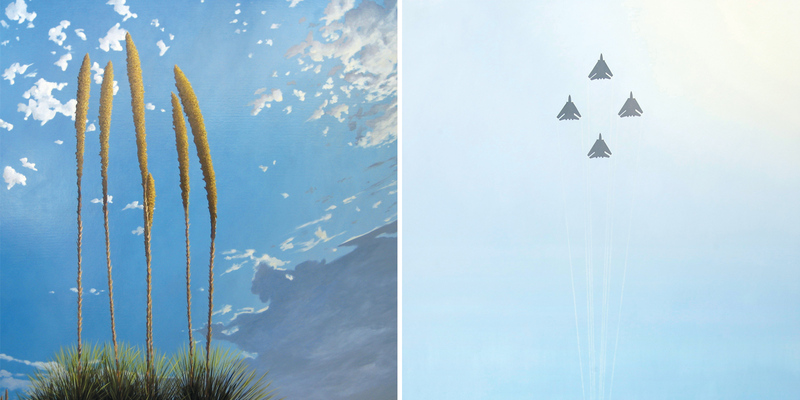

Chris Barnard was driving from Los Angeles to El Paso for a wedding. The landscape was familiar: desolate, empty, and mostly flat, and the only signs of life were exit signs, mostly for military installations. As the miles passed, he thought about the meaning of the American West in the history of the country’s expansion, and the meaning of this land now being the incubator of American military expansion, American power beyond its own borders. He pulled his car over at a rest stop and saw a yucca’s blooming spikes soar upward against the desert sky. In that moment, the benign natural objects became a vision of rockets launching. Thought and image merged to create metaphor, the language of inspiration.

The enormity, the beauty, and the unnerving quiet of the Southwest have been Barnard’s artistic turf since his undergraduate days. His large canvases are always about the visceral experience of vast scale and space, and over the years he has honed in on aspects of human influence within that landscape. In earlier work, power lines and petrochemical plants dot the vast Texas plains, cities sprawl on the desert surface like a synthetic, mathematical blight. The military is a more recent addition to his artistic vision, in which the machinery of war inhabits an American terrain not so different in its starkness from the lands where it’s destined to be deployed. Bombers made to carry nuclear weapons are objects of pride and celebration in the context of American sporting events, but their ominous shapes also imply their purpose half a world away. These paintings aren’t sermons, they’re revelations: beautiful, challenging invitations to step back and look at ourselves and our country, and at our presence on the planet.

—JGH

Exposure No. 4

Exposure No. 4

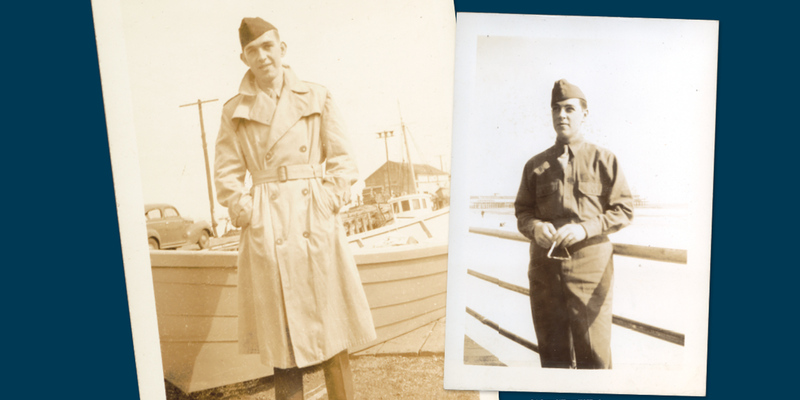

Like Millions of other young Americans in the 1940s, the three Miller brothers of Cambridge, Massachusetts, were eager to answer their country’s call to duty. For two of them, their answer would result in the ultimate sacrifice.

Howard, the eldest, withdrew from Harvard in 1942 to join the Army Air Corps. While training in Idaho during the winter of 1944, he fell in love with the fetching Jeanne of nearby Mountain Home, and they were married shortly before he went to England. A B-17 gunner and radio man, Howard had to survive 35 missions before he could go home to Jeanne and baby Karen, born after he had gone to war. So on Sept. 18, 1944, he volunteered for his 33rd, a dangerous, low-flying supply drop for British para-troopers caught behind enemy lines. Howard and his entire crew died that day over the Dutch city of Eindhoven.

The second brother, Albert, withdrew from Denison in the spring of 1943, after just two semesters. But because of his cursed asthma and allergies, none of the U.S. armed forces would enlist him, nor would the Canadians, nor the British. So Albert signed on as an ambulance driver with the American Field Service and supported the Allied mission up through the boot of Italy. He later found himself in the midst of a fierce battle near Strasbourg, France, and the German border, where Allies had encircled Nazi forces. Returning to the front lines on Feb. 7, 1945, he was killed when a speeding French artillery truck smashed his ambulance off the road.

Having been accepted to Denison a year early, the youngest brother, Bill, withdrew with Albert. He joined the Army Air Corps and trained to fly B-24 bombers. He was in reserve at Westover Air Field in Massachusetts when Albert died, and according to policy the Army gave him the option of a desk job. But after thinking carefully and talking with his parents, Bill remained certain that he wanted to stay with his crew. So in June 1945 he was sent to Southeast Asia, where, to his dismay, he saw no combat—just a lot of cargo delivery. He returned to Denison in 1946 and was given a semester of credit for his military experience. Today, he’s in his hometown of Cambridge, counting the blessings of three children, two grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren of his own, as well as the extensive family of his third wife, Jane.

Howard was reunited, in a sense, with Albert when his remains were found after the war. At their parents’ request, they were laid to rest side by side at the Epinal American Cemetery in France.

–PP