Before 12 million tourists made their way to south Florida each year, before 1,000 people a day started moving to the state, before anyone thought of trying to grow oranges and tomatoes and sugar cane on flood plains, before anyone released an overgrown pet python into the canal, before anyone started messing with the where and when of water, before all of that—there was the untouched Everglades, three million inhospitable acres of razor-sharp saw grass marsh and humid, muck-bottomed swamp with too much rain, too little rain, beastly temperatures, and fiendish humidity. It was not exactly an easy place to love. It still isn’t. The native Calusa, Tequesta, and Seminole Indians understood how to live on such land. But accounts by American soldiers, pioneers, and surveyors never failed to curse the mosquitoes, dread the alligators, and fear the water moccasins. In describing the Everglades, the word “wasteland” came up a lot, followed almost immediately with schemes of how this “worthless” land could be drained. The hubris of man—that this natural world exists only for us, that it is ours to “improve” and bend to our will—is staggering. And yet equally stunning is the fact that there were minds that could actually figure out how to do it—that someone could conceive of the walking dredges, behemoths that scooped out the muck and ooze of the swamp; that someone could design a canal system to redirect Lake Okeechobee’s seasonal floods and dry up the land.

But the canals worked too well. It wasn’t a wasteland before. A century of “progress” moved it in that direction. What is left of the Everglades, its resplendent “River of Grass”—as Marjory Stoneman Douglas dubbed it in her time-tested book of the same name—and its interlocking ecosystems, is dying of thirst. To bring it fully back to life will demand more hubris, more genius—and a lot of resolve, not only from us but from coming generations as well.

Cap'n mike is showing off, whipping his airboat through a narrow passage in a mangrove swamp, then sliding around the bend. It’s just him and me this morning. There aren’t many tourists around. It’s April 30—the end of the dry season and the beginning of the thunderclap deluges and mosquitoes of the rainy season. The skies are marble-blue with the freshness of early morning. The temperature feels good on my skin, and I have yet to get my first mosquito bite.

A great blue heron stands along the shore, stock still, waiting to snatch a fish out of the shallows. We putter along, watching, when Mike, a burly guy with unruly white hair popping out from under his well-worn baseball hat, points out a ripple of water ahead.

“Manatee,” he says. “That swirl is where he’s been. It’s his footprint. Look in front of that. There. Did’ya see that?” My eyes happen on the right spot just in time to see the manatee surface. This manatee is a 1,200-pound, slug-shaped mammal, but all you really can see of him is his snout, which he pushes through the surface to get air. Later I can make out his huge shadowy figure a couple of feet below the water. Legend has it that early sailors mistook manatees for mermaids—although how exactly that could happen isn’t clear to me unless it involved a significant amount of rum. We’re in a manatee zone, which means boats have to go slow to reduce the danger. Florida manatees are on the endangered species list—along with 67 other Everglades plants and animals. The manatee population is estimated to be around 2,800. Last year, 73 were killed by boats.

Mike draws my attention to the water, which looks a little on the toxic side, discolored, tinged with black. That’s from the tannin in the red mangrove, he tells me. The stain in the water keeps predators from being able to see the fish. “It’s what makes this estuary such a marvelous nursery for fish,” he says.

“We probably won’t see alligator this trip,” he adds. “We haven’t had any serious rain in several weeks and the water’s gotten saltier and saltier. Alligators don’t like salt water.”

During the 90-minute boat ride through swamp and bay, I will see a male bat ray with the tips of its wings above water to attract females. I will see a dolphin almost close enough to touch. I will see some osprey and a juvenile ibis with its long and skinny orange beak. And later back at the dock I will see an alligator—a baby kept in an aquarium for tourists to have their pictures taken with—which I will do, despite an aversion to touching reptiles or, for that matter, to appearing tacky. Before I left for this trip, my five-year-old son told me he hoped I wouldn’t get eaten by an alligator. Now a handler passes the alligator over to me, almost as gingerly as you would pass a newborn. It’s a little longer than my forearm. I’m surprised by how boneless it feels, like I’m holding a tube of rice. I smile and say cheese and then happily return it. His caretaker says, “Here. I’ll make him smile for you,” and puts a little pressure on the back of its neck. The alligator’s jaws fall open so that it does almost look like it’s smiling—or begging for a little dignity. I take a picture of this, too—although for the life of me, I’m not sure why.

Water was—and still is—the defining element of the Everglades. But here’s how it used to be: The headwaters were found in the squiggly Kissimmee River, which cut through central Florida and flowed into the enormous and shallow Lake Okeechobee. In the rainy season, Okeechobee spilled over its southern banks onto the vast saw grass prairie below. There, the water seemed to just sit in a sheet 60 miles wide—60 miles!—and anywhere from a few inches to a few feet deep. But in the slightly deeper sloughs, the water was flowing, although only a hundred feet a day. It could take almost a year for a droplet of water to go from Lake Okeechobee in south central Florida to Florida Bay, 100 miles farther at the tip of the peninsula.

But how could water move quickly when the slope of the land was so gradual—less than two inches per mile—and the topography so flat that an elevation of three feet was striking? Everything about the Everglades was exaggerated. A bump of a few inches in the porous limestone bedrock was enough to give rise to forested mounds that were just high enough to escape flooding during the wet season. The world of these tear-shaped tree islands was an entirely different order from the relentless saw grass marsh that surrounded it. Tropical plants like West Indian mahogany, gumbo-limbo with its peeling reddish-brown bark, and the leathery-leafed coco plum grew right alongside the more temperate live oak and red maple. The trees and shrubs created a dense refuge for animals, songbirds, and butterflies, as well as nesting sites for wading birds, alligators, and turtles.

When the water finally made it to Florida Bay, oh my. This was the part of the Everglades that was easy to love. There, in the estuaries, the freshwater of the Everglades mingled with salt water from the Gulf of Mexico and created a little piece of heaven on earth. It was where the Everglades flaunted its “extravagant abundance.” The estuaries teemed with fish so plentiful it could make a fisherman cry. The riot of fish in turn attracted the attention of the birds, and the beautiful, near impenetrable tangle of mangroves protected them. Rookeries abounded—pelicans, egrets, cranes, herons, ibises, flamingos, roseate spoonbills, storks, frigate birds, kites, skimmers, hawks, eagles, and, it must be said, vultures. The colonies of birds were so thick that when they took off they blocked out the sun.

But the relationship between the generous ecology at the southern tip of the Everglades and the landscape the water flowed through to get there wasn’t completely obvious. The two parts needed each other to make a whole. Today, development and agriculture have reduced the size of the Everglades to half the original. The Kissimmee River until recently was straitjacketed into a canal for water control. Seventy percent of the water that flowed from Lake Okeechobee through the Everglades has been diverted through a series of canals. The timing and distribution of the water that is released into the Everglades has nothing to do with the needs of the natural system—and everything to do with the needs of farmers and consumers.

These modern water-management practices have dried out the northern and southern ends of the Everglades and left the central marshes continually, rather than seasonally, flooded. Some of the victims are the ancient tree islands that formed one to two thousand years ago. In 1940, there were 1,251 of them. Today only 581 remain. When a tree island becomes inundated with water, the tree roots fail to get enough oxygen and the trees die. One island as recently as 16 years ago offered important nesting grounds for 1,400 wading birds. Now half of it is under water with only enough trees remaining for a couple hundred birds to roost. The statistic that everyone in the Everglades knows by heart is that 90 percent of the unimaginably breathtaking bird colonies are gone. For every bird you see in the Everglades today, nine are missing. I was thrilled for every brown pelican, great blue heron, white ibis, and snowy egret I saw. But really, it is like trying to make a meal out of a grain of rice.

I’ve just met my second Mike of the day. This Mike is the biologist at the Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park. My encounter with him was chance. I was standing outside the locked visitor center, looking at a map when he pulled up. The noon sun was pointed straight down on me like it was a magnifying glass and I was the ant. I had been weighing the heat-and-mosquito factor, trying to decide if it would be as pleasant as it looked to sit on a nearby bench and eat my lunch in the shade overlooking a little stream.

Inside, one long display shows off some of the 44 native orchids that grow in the Fakahatchee Swamp, including the elusive ghost orchid. Mike Owen is a rangy guy with short gray hair, bright eyes, and a baby’s complexion. He’s got big, floppy hands that gesticulate wildly when he is passionate about what he’s talking about, which is everything. Or at least everything to do with the wildlife at Fakahatchee. I notice a display of native insects. One of them is so big you wouldn’t want to bump into it alone at night—not even in a bright alley. This turns out to be the swamp moth, and my one question gets Mike going for a good 15 minutes of conversation, in which I learn many things. Here are some: Mike has counted 315 ghost orchid plants in the swamp. When it’s not in bloom, the plant blends in with the mottled surface of its host tree. The likelihood of spotting the ghost orchid without a guide pointing it out is almost as good as spotting a real ghost. For an orchid aficionado, it is the holy grail. I learn that ghost orchids grow on popash and pond apple trees, that the scary looking swamp moth is the only known pollinator of the ghost orchid, although it pollinates other plants, and that, interestingly, the swamp moth eats only the leaves of the pond apple. “You have to have everything,” Mike says, his hands lending emphasis to the point.

Mike is heading back out to check water levels in the wells. But before he goes, he shares a few more things that he is excited about. The Prairie Canal was partially backfilled in 2006, allowing more water to stay in the strand. By 2007, the water table had risen 1.6 feet. The Eastern mink is coming back after distemper thinned the ranks in 2004. There’s a bald eagle fledgling nearby. Someone that morning left a note saying he’d seen a panther and her three cubs on Janes Scenic Drive near Gate 12. Mike is really fired up about that one. The iconic Florida panther, which needs 200 square miles of territory for each male, has lost 95 percent of its historic territory. The breed has been so threatened—at one point there were fewer than 30—that in the last decade eight female Texas pumas, a related species, were brought in to mate with the remaining panthers so that inbreeding didn’t finish them off. Mike is hoping to verify the report with his own glimpse of the new family.

Funny he didn’t say anything about the mosquitoes, I am thinking to myself later as I try to walk the 2,000-foot boardwalk at nearby Big Cypress Bend. I forgot my long-sleeved shirt in the car and the mosquitoes have marked me. They’re so relentless that I actually try speed-walking in desperation, hoping that maybe I can outpace them. Note to self: Next time don’t apply the sunscreen overtop of the bug spray. A rustling in the trees stops me dead in my tracks. I hear the piercing screech of a young bird and at the same time feel a shadow—an enormous shadow—moving over the tree canopy above my head. I’ve never seen a shadow so big. For a brief moment, the shadow materializes in the sky and I see a flash of white tail feathers. I may have just seen the bald eagle. I am surprised to feel unaccountably lifted, unexpectedly graced by the majesty of the natural world—of which even the mosquitoes are a part.

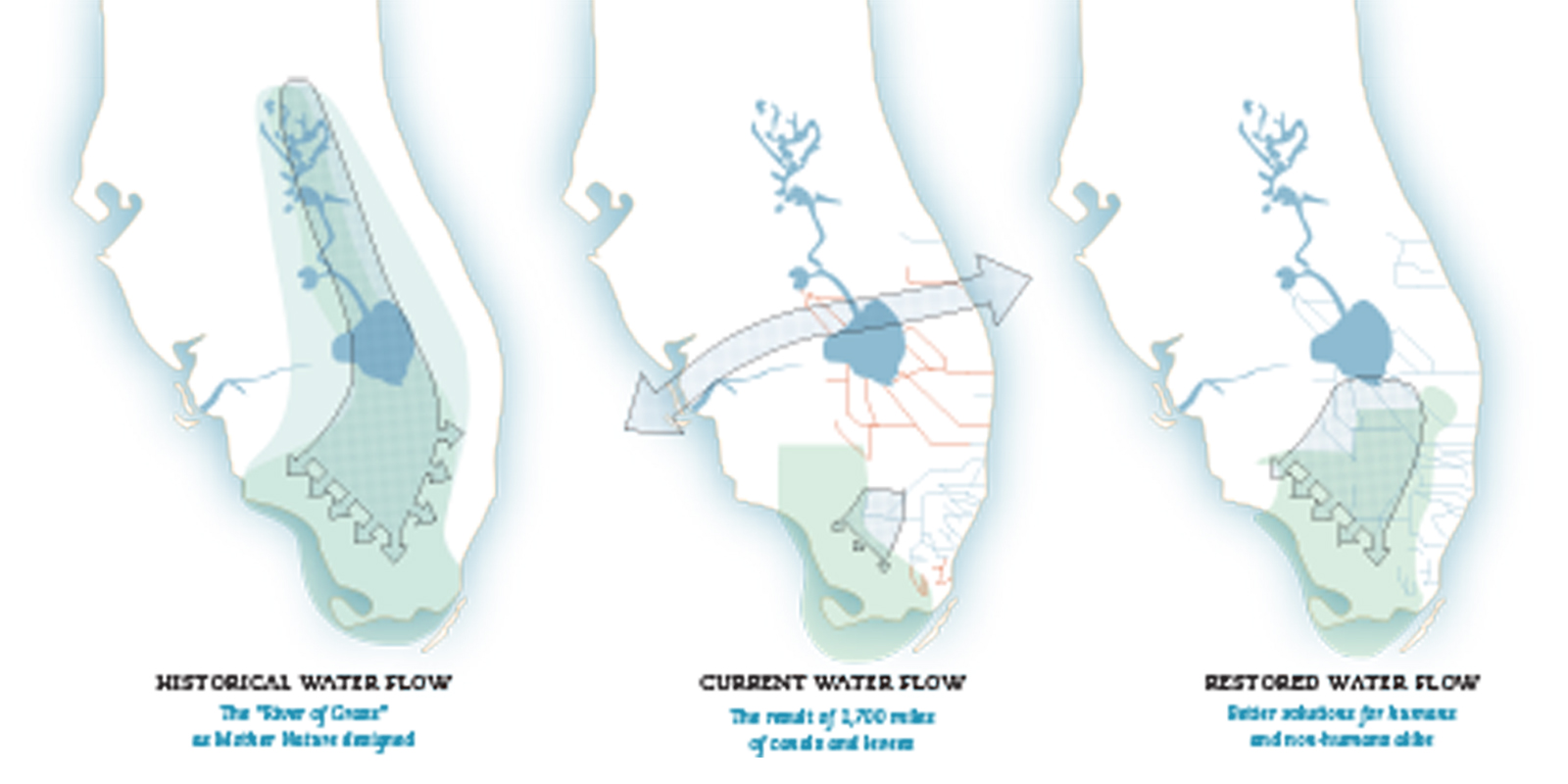

Three maps tell the story of the Everglades about as succinctly—and disturbingly—as anyone can. In the first map, the exuberant swoosh that begins in the Kissimmee River watershed just below Orlando looks like a water slide as it comes down into Lake Okeechobee and then spreads throughout the Everglades to cover most of southern Florida. Eight fingers mark its exit routes to the sea—three to the southwest, three to the southeast, and two down to the Ten Thousand Islands area and Florida Bay. This is how it moved in the days before anyone thought about fooling around with Mother Nature.

The second map isn’t as pretty. Two arms stretch straight out from Lake Okeechobee, one tilted ever-so-slightly to the south, the other with a faint nod to the north. Skinny red lines, like angular spider veins, slice their way to southeastern estuaries and out to the Atlantic. These are the canals. A somber little tail of a swoosh, not even a tenth the size of the first, is an afterthought, teasing the spongy marshes and swamps of the central and western tip of the Everglades without slaking their thirst. This is the current flow, the one that has strangulated the remaining Everglades.

The third map is a snapshot of The Plan, the working idea of how to get the water back into the Everglades, where it belongs. Here the swoosh returns, although there’s a big gap between it and Lake Okeechobee. It is a little smaller than the first—fainter and more subdued. Only five arrows now, it spreads its fingers to the south and southwest. Still, it bears a likeness to nature, a resemblance to the once mighty spread of the creeping river.

This is where Dan Kimball ’71 comes in.

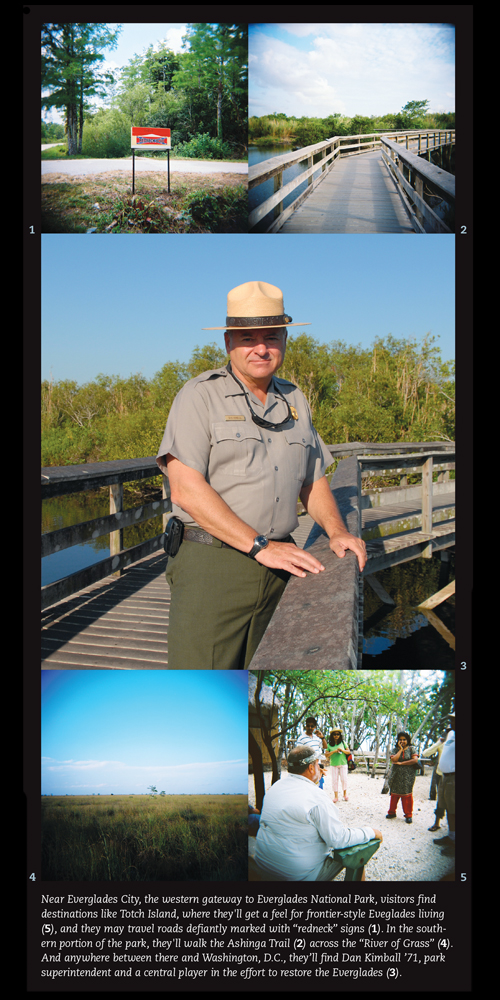

Since 2004, Kimball has been superintendent of Everglades National Park, 1.5 million acres that preserve most of the undeveloped lower Everglades. An expert in water management, he honed his skills in the western states as chief of the National Park Service Water Resources Division. The vista in Florida is about as different as it gets from his former home in Colorado. He shakes his head every time he passes the “Elevation 3-feet” sign on the park road when he travels to Flamingo, the park’s outpost at the tip of the peninsula. Still, he’s come to love the terrain. Montana’s Big Sky Country, he scoffs. He tells his friends this is really big sky country—180-degree vistas, sky all the way to the ground everywhere your eye falls. Except everywhere his eye falls, he can see the signs of an ecosystem in peril. Invasive plants and trees like the Old World climbing fern smother entire tree hammocks with their dense foliage, and Brazilian pepper trees blanket the landscape. The only way to eliminate the Brazilian pepper is to scrape the soil all the way down to its limestone bedrock and then haul it away. Surprisingly, that does the job.

Kimball has a mantra: quality, quantity, timing, and distribution. If they can get these right, they can get that swoosh of water back into the Everglades. Then the ecosystem will pretty much restore itself. That’s what happened in the lower seven miles of the Kissimmee above the lake when they let the river return to its historic channel.

Bringing the flow of water back to the Everglades begins way above the park’s northern borders. The Plan—the $7.8 billion, 35-year Comprehensive Everglades Restoration Plan (CERP)—will dismantle the incredibly efficient system that controlled the floods, that allowed big agricultural enterprises to prosper in the former floodplain of the giant lake, that brought ample water to slake the thirsts and lawns of exponentially-expanding communities of Southern Florida. The problem is, any new water system still has to provide for these modern needs. Case in point—the troublesome 8.5-square-mile area east of the park where development occurred on the wrong side of the protective levee. Kimball can’t allow the restoration of the Everglades to put these homes at risk for flooding. That would be the end of the restoration. But how to satisfy these modern needs and still return enough water to ensure the health and survival of the Glades? That’s the trick.