Eighty-year old Tai Shigaki approaches an area of urban Bangkok that receives few visitors. She raises her arm to ?lter the stench that comes from this, the worst of the city’s slums. She enters, wondering how anyone could work here, let alone live here. This is where they take the garbage that the city dumps turn away. And this is home to families who are outcast from their own country and the city where they seek refuge.

It is 2002 and Shigaki is here to visit a family who attends one of the city’s few Baptist churches. As she arrives at their shelter made of wood and metal scraps, Shigaki is surprised at the warmth of her hosts. They greet her and offer her a place on the ?oor to sit. She learns that the husband works in another city dump. Their young children also work. The mother, who is blind and cannot walk, tends to their modest home. But on Sundays the family treks many miles across town to attend Sunday service.

And so the Granville and Denison communities braced themselves for the changes that might come with the arrival of Japanese Americans. An editorial in the Sept. 30, 1942, Denisonian addressed the tension: “Members of the Denison community and townspeople are faced with a mental conflict between patriotism and courteousness with the pending arrival of five Japanese-American students who will be attending Denison.”

Shigaki has traveled to Thailand from her St. Paul, Minn., home to observe the work of American Baptist Missionaries and to witness the plight of refugees from the Karen State of Burma. The Karen, introduced to Christianity in the early 1800s, have been ?ghting the Burmese government for greater autonomy for more than 50 years. Like nearly half a million other Burmese, they had to leave their homeland or face death. In Thailand, where it is illegal to live if you are not a Thai citizen, the Karen make their homes in refugee camps or, worse, underground in the city’s dumps.

Because the Karen are not permitted to work in Thailand, their employment is also an underground activity. Men may be involved in the drug trade, while young girls are enticed into prostitution. The American Baptists are there to help break the cycle, and Shigaki does her part by making pastoral visits. She sits in on a class to help train young women in the art of making arti?cial ?owers. She attends a meeting for families suffering from AIDS. In short, Shigaki does what she has always done: seek out the outcast and help change the course of their lives. The octogenarian is taking this on at a time when she has every justi?cation to slow down. But Shigaki is on a mission to help victims of circumstance. And it is a mission that has quietly but constantly consumed her life since she herself was removed from her home and consigned to a Japanese internment camp during World War II.

Why would Shigaki, now 85, tirelessly dedicate herself to raising up the lives of others? To her, there was never a choice. She describes the journey as one controlled by a higher force. She was destined to work with the displaced because at every stage of her life she would ?nd that a door would close, and when that door closed, only one other door would open. The doors that opened led her closer and closer to working with those who found themselves trying to make a home in a new place.

The ?rst door closed when Shigaki was six; her father died at their home in Southern California. Her mother, a dressmaker who worked in the home, remarried and the stepfather, a deep-sea ?sherman, was often away ?shing in Mexican waters. In an effort to keep occupied, and perhaps establish her own identity, Shigaki joined a youth program at the local Gardena Japanese Baptist Church. Her parents, mild Buddhists, didn’t pay much attention and thought it was good for their daughter to have some exposure to U.S. culture. But they didn’t realize that this newfound curiosity would set the course of her life.

Shigaki remembers the day she realized her vocation would somehow be connected to the church. She was sitting in the social hall at Gardena with several dozen other Japanese American Baptist youth. At the head of the crowd was a young, smart-looking seminarian, Jitsuo Morikawa. He spoke perfect English as he delivered his sermon—an intellectual message that stretched the young minds in the audience. His passion moved Shigaki to believe that she had to seek a deeper reason for being part of a church community. (Morikawa would later send his son, Dennis Morikawa ’68, to Denison. In the year that Dennis graduated from Denison, Pastor Morikawa gave the baccalaureate address and Dennis served as the student commencement speaker.)

Initially Shigaki focused on doing right and saving her own soul. She thought that her salvation would come from being good and conscientious. That notion was altered when she enrolled at Los Angeles City College and joined the college’s Baptist student group. There she befriended Denison alumnus Gale Seaman ’05, who served as a volunteer director. According to Seaman, in order to live out one’s Christian values more deeply, one had to actively seek justice for others. This message became Shigaki’s mantra for the rest of her life. Seaman’s participation in her fate would grow deeper in the months ahead when the nation went to war and Shigaki was forced to end her California experience.

As Japanese military action escalated in 1940, rumors circulated that Japanese Americans would not be permitted to live on the coasts. Shigaki’s parents moved to Utah to avoid con?ict, and she transferred to the University of Redlands thinking that was far enough from the coast to be a safe haven. But when 360 Japanese bomber and torpedo planes devastated Pearl Harbor in the early morning of December 7, 1941, Shigaki had a feeling that life for Japanese Americans would change forever. On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which forced the relocation of 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry—two-thirds of them American citizens—to military internment camps. That spring, Shigaki was instructed to report to the train station. The news left her numb, but she and all of the others who were noti?ed dutifully followed orders. Shigaki packed what few possessions she had and boarded the train for a location unknown to her at the time.

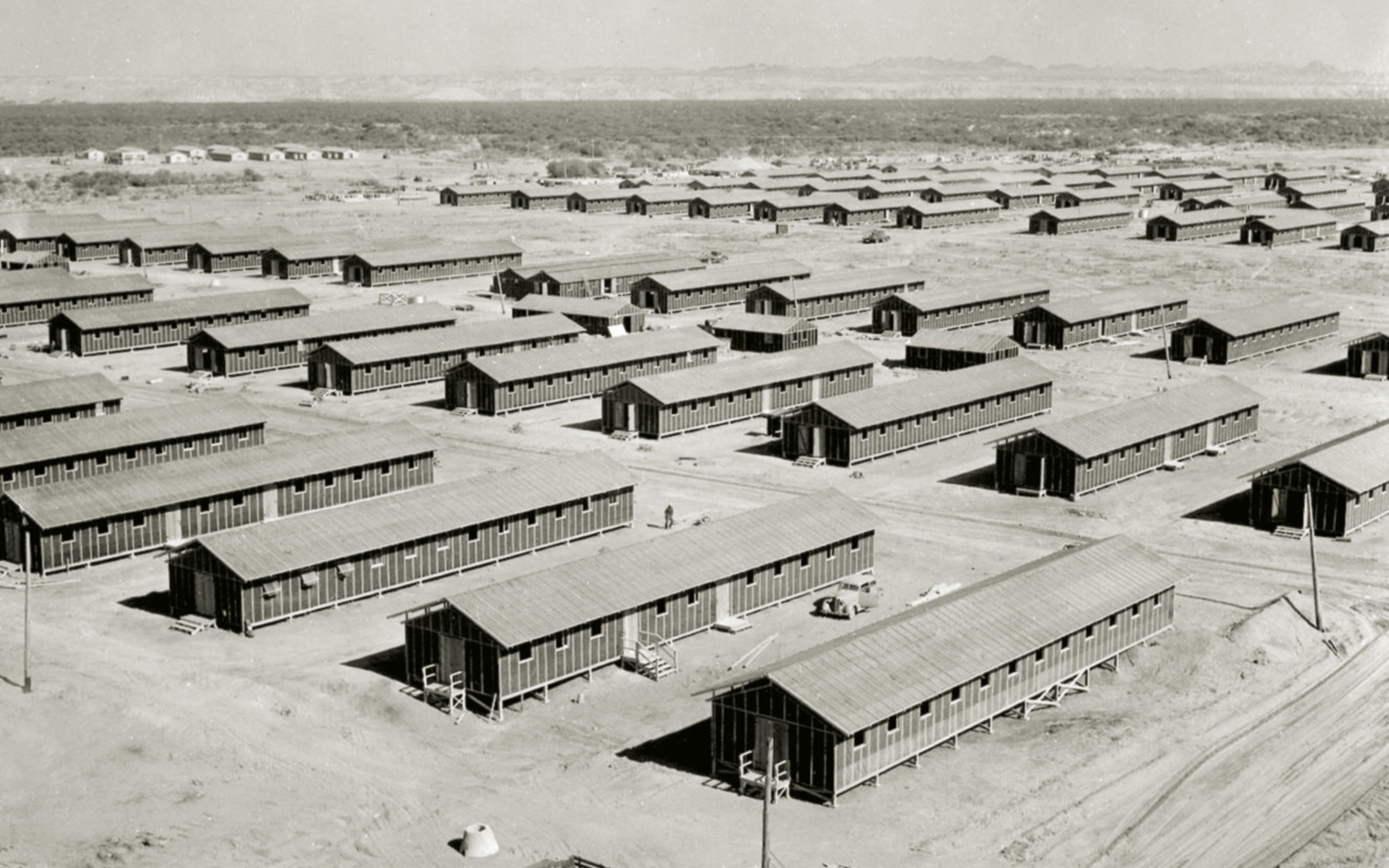

Poston 1 in Arizona was one of the ?rst Japanese internment camps to open in the United States, and Shigaki was one of its ?rst inhabitants. Because she was under 21, Shigaki attended Poston with the understanding that she would soon be permitted to reunite with her family. Knowing that her stay at Poston would be short-lived enabled her to keep a positive attitude.

Shigaki is apologetic about her four months in Poston because she feels she didn’t suffer as much as most of the other inhabitants. Because she had little, she felt she lost little. Because her family was not with her, there was no one to worry about. But the reality of her situation was far different from her own perceptions. The wooden barracks had no insulation and the winds brought sand and dust through the cracks in the walls. The tarpaper-covered roofs would bake in the 130-degree summer heat. There was no rice, a Japanese staple, and the food was bland. Shigaki would have to time her visits to the common bathroom for the middle of the night so that she could have some privacy in the group shower, or to use one of the dozen or so unenclosed commodes.

Shigaki was at ?rst assigned to the all-single-women’s barrack, which sat next to the all-single men’s barrack. She wanted no part in bumping into the single men at all hours of the night so she and a friend found a small family who needed people to ?ll their barrack quota. She kept her mind off her situation by getting busy. While some Poston residents gardened, wrote poetry, or explored new interests, Shigaki quickly immersed herself in trying to have an impact on the community. There were no means of communication among those interned so Shigaki launched a newsletter with some of her fellow Baptists. To her surprise, Pastor Morikawa also arrived at the camp, and though she was sad that he had to endure life there, she was also comforted by being able to work with one of her mentors. All the while, Shigaki waited and waited, but removing minors from Poston was not a priority for the authorities.

Shigaki initially re?ected very little on her Poston experience because like many nisei—the term for second-generation Japanese Americans—she thought it was impolite to publicly discuss unpleasant things about herself. But she later wrote about her internment in the book Re?ections, a collection of ?rst-person accounts of camp life. She described what it felt like to have no news of her pending release: “We suffered the straw mattress, the lack of privacy in the common shower room, bedroom, toilet facility, and the poor food in the mess hall with the knowledge that this was very temporary. As the days went into weeks and months, the lark was no longer very amusing. And each day we watched hundreds of new evacuees coming and heard their tragic stories of how they were uprooted, having to leave behind most of their possessions.” The Poston experience was a test for Shigaki. “Being young, naïve, and perhaps a bit dramatic, I thought of this period in my life as a testing period akin to the Jewish people wandering in the wilderness with Moses…. The Arizona desert felt like a good ?t with the Sinai desert.”

While Shigaki waited for a transfer to Utah to be with her parents, Gale Seaman was taking his own action. He was communicating with his alma mater to seek a place for his friend. It turns out that Denison was making a bold move at the time by looking to take in several Japanese American students. College president Kenneth I. Brown wrote a letter to the board of trustees that reveals the abrupt language then-used in reference to Japanese Americans: “We have been asked, along with other colleges, to take our share of the Jap students who must be evacuated from Paci?c colleges…. The faculty Executive Council has agreed to accept not to exceed six Jap students, when they come with satisfactory academic records, with personal recommendations from their President, and with suf?cient ?nancial backing to complete their year.”

And so the Granville and Denison communities braced themselves for the changes that might come with the arrival of Japanese Americans. An editorial in the Sept. 30, 1942, Denisonian addressed the tension: “Members of the Denison community and townspeople are faced with a mental con?ict between patriotism and courteousness with the pending arrival of ?ve Japanese-American students who will be attending Denison.” The piece went on to say, “Each of these individuals who are American born, American raised, American educated individuals, comes fully recommended. Each one desires a college education just as you desire one. Each one respects and cherishes the hopes of this country just as much as you do. They will study hard. Their time at Denison can be valuable and enjoyable if the Denison community welcomes them in a patriotic and zealous manner.”

The news that Shigaki had been accepted at Denison ?nally triggered her release from Poston. She will never forget that cold January midnight in 1943, when she got off the bus in front of the drugstore on Granville’s Broadway. It was dark and she was alone, but she wasn’t frightened. The place felt peaceful, and when the village policeman drove her uphill she was content to sleep on the couch in a residence hall on the East Quad, then the women’s end of campus. Arrangements had been made for her to stay with the Richards family near campus. Cyril Richards was dean of men, and Alice Richards was like a mother to every student she met. They thought Shigaki was arriving by train and had awaited her at the depot. But in the morning Shigaki woke to ?nd Mrs. Richards at her side. They went home together, went to church, spent the day learning about each other, and began what would become a lifelong bond. This experience of ?nding a safe, welcoming home became the ideal that Shigaki would wish for others.

The Richards’ daughter, Margie, and Shigaki became roommates. Margie, a bright and energetic Denison student, was well known around campus. She had met a man from Dartmouth College at a student conference and they fell in love. The couple’s relationship is chronicled in Kenneth Brown’s book Margie, The Story of a Friendship as Told in Part through her Letters. Shigaki remembers all kinds of excitement swirling around the Richards home as Margie got pinned on the very day Shigaki arrived. Margie recounted Shigaki’s arrival in a letter to her beau: “But most exciting of all—besides the addition of certain tinnery—is that Tai Shigaki is here….

What a radiant personality…. Her sense of humor is marvelous and just clicks with mine, so that we have a continued riot. We can be serious, too, of course, and seem to have a lot in common. She’s so cute about my pin, too. She shares my excitement just as though it really meant something to her, and she hardly knows me.” During that semester they became as close as sisters.

That spring Margie traveled to a Maine camp for another student conference. Shigaki’s newly formed friendship was shattered when Margie’s canoe washed ashore empty late one afternoon. Her body was never found. Shigaki expected to take the role of helping Margie’s parents through their ordeal. But when she saw the Richards descend the stairs on the day of the funeral with warm smiles, she knew that it was going to be the Richards that would help Shigaki and others cope with their loss. The Richards, who on that day taught her a valuable lesson in grace under pressure, took Shigaki in as their own and their home was her home from that point on.

Doors continued to close and open in the years following Denison. After obtaining a master’s degree in religious education from Newton Andover Theological School, Shigaki became a religious education director at a congregational church in Hawaii. She then returned to the mainland to help grow a community center in a deteriorating part of Minneapolis. The ?rst-hand knowledge of what it was like to be displaced stayed with Shigaki and she continually found opportunities to work with new arrivals to the area. She worked in a settlement house, and then at an international institute where she helped foreign-born immigrants, including Japanese war brides, adjust to life in their new home. Her good work was noticed and she was eventually asked to be the executive director of the University of Minnesota YWCA, helping students who were making the university their new home. Shigaki earned a master’s degreee in social work from the University of Minnesota, where part of her training included working with prison inmates. There, Shigaki faced her ultimate test: affecting those who had reached a low point in their life and in their sense of place. She became the assistant director of staff training for the Minnesota Department of Corrections. She was the ?rst and only woman to serve in top administration in a career that lasted for 25 years. superintendent of the Minnesota Women’s Reformatory, and later the During that time, Shigaki educated prison staff members on how to work with inmates as individuals. She arranged scholarships so correctional of?cers and other staff members could get master’s degrees in social work, and she encouraged a vast majority of high-level staff to receive advanced degrees. She believed that no matter what circumstance caused their imprisonment, the only way to help prisoners seek a better life was to treat them with respect. “Having experienced incarceration myself, I was very aware of the fact that the worst thing about imprisonment is not poor living conditions but the removal of freedom,” Shigaki writes in Re?ections. “Having a sense of that deprivation, I was able to empathize with the inmates and help them not only to get beyond focusing on their plight, but also to learn how to control the behavior that resulted in their imprisonment.”

If you were to ask the modest Shigaki how she keeps busy in retirement, she would say that she volunteers for her church and leave it at that. But press a little more and you’ll learn that she was never less active or less sincere in her effort to help victims of circumstance. When word came that the Vejzovics, a Bosnian family, made it to the Twin Cities from war-torn Yugoslavia, Shigaki taught Mrs. Vejzovics English. When the Kibret family ?ed Ethiopia, Shigaki helped them try to gain U.S. citizenship. When the Multicultural School for Empowerment was looking for volunteers to help Hmong refugees from Laos learn English and get resettled in the U.S., Shigaki volunteered to work with those families on a weekly basis. And after returning from Thailand on that trip four years ago, it is Shigaki who has helped Karen families to emigrate to the United States and make their home in Minnesota. She now trains others on how to help new U.S. residents make their way in a foreign land.

It is interesting, and perhaps ?tting, to note that a fellow Denisonian is witnessing Shigaki as she continues her personal mission. Her current pastor at the University Baptist Church is Doug Donley ’83. Donley admires the work that Shigaki has done at the helm of the Asian-American caucus of the American Baptist Church, as a founding member of the Baptist Peace Fellowship, and as a contributing member of one of the many national boards on which she has served. But his most vivid image of her is in their church’s backyard, where this woman, who has witnessed unimaginable conditions and heard countless heartbreaking stories, sets up a small booth upon which she displays little plastic ?owers. She sells them to raise money for new Karen arrivals. They’re the same ?owers made by the young Karen women back in Thailand. And so the woman who was once an outcast herself carries on in her mission to lift the spirits of other outcasts struggling to ?nd home in a new place.