He wants the students to understand the deeper meaning of working with Habitat—the importance of building a home for someone who has none.

“This project deals with geometry and engineering, but also with empowerment and social and political issues.”

It’s Oct. 8, a dreary Saturday made even more wretched by a bone-chilling drizzle—the kind of day that inspires dirges or thoughts of long hours under warm blankets. A day that brings to mind Dylan’s “Shelter from the Storm.”

On Monroe Street, that empty lot isn’t so empty anymore. There is now a one-story square-ish house under roof. A trail of plywood leads from the street to a frame of a porch. There’s a sign to the right, announcing this is a Habitat for Humanity project, listing Denison and Owens Corning in big type, as well as, in smaller point size, the names of 17 other sponsors. Inside, the sub-flooring is down and the studs are in. You can make out the compact floor plan—front door opens into the living room, kitchen to the right, the utility room over there, the bathroom on that side and the three bedrooms. There’s plenty of work left—insulation, dry wall, siding, painting, and landscaping, among other things. On this morning, Downs is here with four volunteers, including a Denison student, Jack Pearson ’09, and his father, Todd, who’s in from Olympia, Wash., for Parents Weekend. The rain and the project schedule result in a rare light day for Downs, who’s wearing a brown floppy hat, tweed sports coat, relaxed yellow dress shirt, jeans and tennis shoes. He has a full gray beard and an etched face you don’t find on someone who works in an office.

Downs pulls the crew tight for a quick session. He needs 14-inch-long pieces cut from a 2 by 4. Sounds simple enough. Yet Downs uses a stud as a chalkboard and, with a pencil, diagrams the purpose of the boards—something to do with how a gas line will run. It’s not necessary, but Downs, as he regularly does, wants the volunteers to understand how their action of cutting a certain length of wood fits into the bigger picture of building a house. Patient and low key, Downs is leading a crew that includes some people who’ve never used a screwdriver. Pearson appreciates the lessons. He is part of the To Have a Home class that comes here on Wednesdays. He shows up on Saturdays on his own. “For fun,” he says; the Eagle Scout likes to build stuff. He tries to coax friends out of bed at 7:45 on weekend mornings to put in four hours with Downs. Pearson’s eyes reflect the energy and passion of youth.

He says he’s met Michelle Johnson, the prospective homeowner, while she’s been there clocking in her required hours, as well as her 4-year-old son and 2-year-old daughter. Pearson gets a kick out of the boy. “He’s funny,” he says. “We find his Matchbox cars in the yard.” Pearson then points out the work he’s done, from installing studs to shingling the roof to working with the electrician. Todd hovers by, listening, and his sense of pride is easily apparent. Then the two go off to drive nails into boards, the dad securing the wood with his foot while the son swings the hammer.

Sadie Orlowski ’09 from Charlotte, N.C., also arrives with her father, Rick. Like Pearson, she’s in Kennedy’s class. Unlike Pearson, this kind of labor is new to her. “I’ve never been much for construction work,” she says. Orlowski recalls the first day the class came to the site, with a bunch of them wearing flip-flops and shorts. Their job was to sort wood. But in a matter of weeks, they were climbing a ladder to get on the roof to secure shingles—looking, as she says, “Like real construction workers.”

Downs sees Orlowski and cheerfully calls out, “Ladder Girl,” causing her father to smile. There is no work left to do today, however. But instead of sending them away, Downs expresses his “deep appreciation” for taking the time to come to the house; he then explains in detail to Rick the work the students have been doing. It’s another teaching moment.

Downs is a perfect match for the project. Aside from his ties with Denison, he once served on the local Habitat board of directors and acted as the site manager for seven of the first eight homes it built. By profession, he is an independent contractor, essentially a one-man show doing home renovation.

To meet the demands of being a husband and father, he stepped aside from Habitat for several years. Then Kennedy contacted him about this collaboration involving Denison and Habitat. He saw a way to tie together two important aspects of his life. “It’s cool when divergent interests converge,” he says.

The project plus his regular job is forcing him to put in 80-hour workweeks. A lot of his time spent here is not on the building, but on the organizing. He has anywhere from a handful to up to 100 volunteers on the site (more commonly 20 or so). And, because Downs is who he is, there are those little lessons to teach: about safety and learning new skills. In addition, he wants the students to understand the deeper meaning of working with Habitat—the importance of building a home for someone who has none. As he says, “This project deals with geometry and engineering, but also with empowerment and social and political issues.” He picks up a red toolbox, heads through the doorway into the rain and along the plywood path toward his truck. A visitor who had stopped by to check on the progress of the house asks him if he can return later. “Sure,” he says with a broad smile. “And I’ll put you to work.”

“We got to know each other really well, there was a distinct sense of intimacy,” Kennedy says of her To Have a Home class. “They took risks by telling stories about their lives. At the site, there were physical risks. They had to depend on each other.”

The Stevie Wonder song “Living for the City”, about the influences of home and neighborhood, is playing through a computer as students settle into their seats in room 117 in Higley Hall. Kennedy enters, turns off the music and takes a seat in front of the class. The point of To Have a Home is to explore how a home shapes you; the impact of neighborhood (suburban vs. industrial, poor vs. wealthy) and homelessness. These ideas (and the Monroe Street house) take on a new relevance in the wake of the hurricanes that devastated New Orleans and coastal Mississippi just weeks earlier.

Today’s talk centers on a book about a couple of kids living in a tough neighborhood. Kennedy asks whether environment influences imagination. The students, it appears, grew up in favorable circumstances, not having to worry about, say, gunfire crackling outside their bedroom windows. They talk about playing make-believe in their rooms or yards and then contrast their experiences with the boys in the book. Some students say the children living in poverty use imagination to escape their daily horrors. Others argue their imaginations are limited because they have to be wary all the time. As one says, “They still have imaginations, but nowhere to express it.”

Kennedy interjects that while the students associate imagination with pleasant memories, the boys in the book use theirs to scare themselves. That is, if they hear gunshots they think the worst—someone is going to die. She asks: “Do stimulants lead you to how you use your imagination and therefore influence how you see yourself?” By the end of class, the talk turns to Monroe Street. Pearson, who hasn’t said much during the discussion, becomes more animated. He jumps in to say he’ll get a van to take students over to the house. Meanwhile, the topic of homelessness becomes real when Kennedy asks for volunteers for another project. A Denison students’ mother—an evacuee from New Orleans—had been living in a motel in nearby Heath before finding a new living arrangement. Kennedy asks if anyone is interested in helping the mother with a furniture delivery. About half the class raises their hands. The other half goes with Pearson.

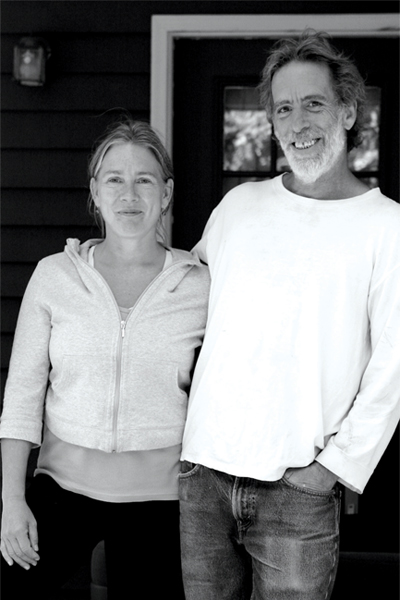

Skillful, caring, and modest carpenter Richard Downs ’77 met his wife, Granville native Kim McPeek, shortly after he graduated, when he was the advisor for the Homestead. “She was the only person who could get me off that hill,” he recalls, “so if you want to put my photo in the magazine, then she should be right there beside me.”

It’s one of those prized November days: sunny and breezy, with the temperature in the 70s. Downs is working with three female students in the front yard of the Monroe home, talking about unloading the drywall from a vehicle and carrying it into the house. He shows them where to position their hands and how to brace the large sheets against the wind. “Are you OK?” he asks as he and one student haul a sheet inside.

The exterior is taking shape: gray vinyl siding, a stone finish on the lower portion of the foundation. The sidewalk is poured and set. Inside, Owens Corning R-19 Fiber Glass Insulation is stuffed between studs, most of which are now covered by drywall. The plastic and copper piping are in place. As the Supremes sing “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” on the radio, one student trims drywall with a box cutter and a straight edge while another takes measurements along a wall.

Days later, Kristen McCloud, president of the Licking County Habitat for Humanity, talks about the project. This house is number 19 for the branch, which formed in 1987. This is the sixth Habitat house on Monroe. Might as well call it Habitat Lane. Why so many on this roadway? “Cheap property,” she says. (About $6,000 per lot.) Also, sewer and water are available and the City of Newark has lent financial support. For instance, it bought one house that needed to be torn down and also paved the street and fixed drainage problems.

The impetus for this collaboration came from Denison because of the academic year’s “home” theme. The idea faced a possible complication, however: Habitat is a faith-based organization (members say prayers at dedications and such) while Denison isn’t. “There was some nervousness,” says McCloud about Denison. But she adds, “We never require you to pray. You don’t have to belong to a church to participate. It has all worked out beautifully.”

She couldn’t be happier about the house’s progress, particularly since Downs is running the show (assisted by Habitat’s normal site supervisor). “What a fabulous guy,” she says and describes an early incident in which Downs made a painstaking effort to make sure some tiny detail was being done correctly. “I knew then I didn’t have anything to worry about,” she says. She adds that working with Downs is like “a Zen experience.”

Without Denison and Owens Corning pitching in 60 percent of the $50,000 cost, McCloud says house No. 19 wouldn’t have been started until many months later. And the university’s involvement also allowed McCloud to witness, for her, an unusual occurrence: Denison president Dale Knobel swinging a hammer while wearing a pair of jeans. “It’s not a sight you see every day,” she says.

She hopes Denison and the chapter will continue to work together. Her goal, even though her term as president ended at the end of 2005, is for the two to build one house per year. “Denison students want to give back to the community,” she says. McCloud adds, “After they graduate and go off to the world, I would like to think they will look for Habitat” as a way to volunteer in their communities.

December 7 is the last required day for Kennedy’s class to work on the house. Many of the students, though, don’t want to stop. They say they are coming back the next week. It has become more than walls, a roof and a foundation for them. The students realize that they’ve made an impact. “Their investment has increased since it started,” Kennedy says. “Some were afraid at first that they wouldn’t be able to contribute. They found, though, that most jobs are doable. So they felt confident to make a contribution. They are also seeing the house as somebody’s home, a home for an actual family.” For some students, that point was made clearly when one bedroom was painted pink. It told them a little girl really would be living there.

“Going to the site changed the tenor of the class,” she says. “We got to know each other really well; there was a distinct intimacy. They told their personal stories of growing up in a home, growing up with divorce. Three students are from other countries. This required them to take risks by telling stories about their lives. At the site, there were physical risks. They had to depend on each other.”

As it turned out, the segment on homelessness wasn’t talked about much. Students became interested in the nuts and bolts of buying a house, so Kennedy invited speakers to discuss mortgages and credit scores and the like. “This brought the impact of the house for this family home to them, the realization that it would be years before they could get this opportunity.”

She, too, has nothing but praise for Downs. “He is definitely tired. But he is also so unlikely to talk about that—the fatigue, being stretched thin—he carries on, committed to seeing the family in the home as soon as possible,” she says. “There are days he has held the students accountable—coming down hard on them. In one case, it was with the drywall. It was not as smooth as it could have been. He reminded them this is somebody’s home. Give it care.”

As for herself, Kennedy wasn’t scheduled to teach a class this semester. But since she couldn’t find anyone who wanted to lead this session, she took it on. Now, Kennedy says, “Because of the students, their willingness to do the project and talk about their stories, this is the best teaching experience I’ve had.”

Jack Pearson ’09 and a volunteer from the local community.

The weekend before Christmas finds ice and snow on the ground and a wreath hanging on the front door of the Monroe house. Inside, Downs is sweeping dirt on the floor into a pan; two guys are in a back bedroom installing closet systems. Michelle Johnson walks in. She and Downs talk about the final few items left to complete the house: carpeting, some painting…. He shows her the kitchen countertop (made of poured concrete) and begins to stroke sealant on the surface. Downs says that soon they’ll put together one last to-do list, and then he remembers he still needs to crawl underneath the floor of the back bedroom to tack in three pieces of insulation.

While it is close to completion, Johnson—who has been living with her parents in Newark—won’t move in until she completes a Habitat-required homeowner’s course in early 2006. By then, Downs will have returned to the normal rhythm of his life. And happily so. It’s been a tough six or so months, compounded by the death of a brother-in-law. At times, he says, he questioned his involvement in the project. But then something happened.

“There were these two co-eds. They were driving me absolutely crazy. Coming here and sleep walking, yapping about cellphones and boys. Just driving me crazy. Made me wonder if this experience really was going to make a difference,” he says. “Then in the last three or four weeks they started to come not only on Wednesdays, but Saturdays, too—even after classes were out and exams were over. What’s gotten into them? Well, my son [who’s in his early 20s] was here working one day when they were here and he ended up talking with them. And they told him that meeting Michelle and her children made a difference to them, that Michelle was dependent on this house.”

Downs pauses and then says, “It was the best thing to happen to me. It gives me a certain amount of hope.”