House of Jerry: Early ’80s nickname for a Denison University chapter of the Fijis (the Phi Gammas), one of many Deadhead frats and Head-friendly student co-ops on campuses across the land that bring collegiate Heads together and serve as informal hostels for Deadheads on tour. —Skeleton Key: A Dictionary for Deadheads, David Shenk and Steve Silberman, 1994

It sounded as if the music was coming from the star, fellow students would tell Andy Acker ’83.

Acker lived in the penthouse of the Fiji house, and on that top floor, behind a wall adorned with a Fiji (Phi Gamma Delta) star, there was a massive speaker that played a constant stream of Grateful Dead.

Acker had been lured into Fiji by this very same siren song as a freshman in 1979. He had seen the Dead for the first time that summer and headed to Denison already hooked. During rush, when the fraternities would play music to entice potential recruits, Fiji was always playing the Dead. It was an easy choice for Acker.

The pull of the subculture is strong: Dead fans have bonds forged in a deep, shared understanding of the supremacy of their music and the warm ethos of the scene surrounding it. (To wit: the first day Beck Fisher ’84 stepped on campus as a freshman, he saw Acker wearing a Dead T-shirt and struck up a conversation. They are friends to this day.) From the outside, though, the Dead scene can resemble a cult: A fervent devotion that saw fans follow the band across the country and even the globe; a cultural ecosystem that happily exists outside of the mainstream; and the worship of sacred texts—live field recordings of the Dead at their untethered best, where songs would segue seamlessly from one to another, wandering on paths that varied from show to show, creating hundreds of totally unique concert recordings that inspired both personal devotion and tailgating debates.

These shows became a cultural currency of sorts, carefully transferred from cassette to cassette, with fans amassing vast libraries. When Fisher and fellow freshman Neil Goldblatt ’84 joined Fiji, the two brought almost 1,000 tapes with them to the house. “It was like a jackpot,” remembers Acker. “Those guys totally upped the ante.” A few years later, Acker paid it forward. Prescott Carter ’88, having heard the legend of Acker’s collection from his Fiji brothers, spent President’s Day weekend at Acker’s place in rural Coudersport, Pennsylvania, making copies of his tapes.

Those connections built around the Dead’s music tended to stick. “I would continue to have my college social group meet up even after graduating by planning to meet up at these shows. We’d use the concerts as connection points to get back together,” says Acker. “We socialized around what we understood as the idyllic time of our lives from college.”

And it was at one of these shows that Acker and Carter, both longtime consumers of the Dead’s mythology, would become part of it.

It was July 4th weekend in 2007, when Acker and Carter met up at the “Grateful Fest,” a collection of Dead-esque acts at Nelson Ledges Quarry Park, about an hour east of Cleveland. There, gathered in an RV trailer at the concert’s campground, Rob Eaton, a friend of Carter’s and a guitarist and vocalist in Dead tribute band and Grateful Fest headliner Dark Star Orchestra, detailed the saga of Betty Cantor-Jackson, the Dead’s former recordist known for her mastery of the band’s sound during its heralded ’70s era. The summary Eaton offered: Cantor-Jackson had made recordings of some of the Dead and Jerry Garcia’s finest work and then—due to a series of financial hardships in 1986—had lost her house and then control of the storage units that contained her belongings. Among those belongings, Eaton said, was a mother lode of Cantor-Jackson’s personal collection of master recordings.

It was Cantor-Jackson’s name that gave these recordings such prestige. The Dead were revolutionary in their laissez-faire approach to their live music, allowing audience members to set up mics at their shows and record them. But even with top-notch equipment, the best audience recordings didn’t compare to the clarity and balance that you could get from tapes that were made directly from Betty’s personal mixing board and reel-to-reel setup. Indeed, her mixes were so revered that Jerry Garcia would regularly stop by her place the day after a show to hear her tapes. “I’d make him a cappuccino and cut his hair,” she told The New Yorker in 2012. (“Jerry trusted Betty to capture his sound so he could hear himself and use the recordings as a mirror into his performances,” says Acker.)

What Acker heard that night was that these prized recordings—which would come to be known as “The Betty Boards”—had been broken into three lots at auction and had been sold to three different buyers.

What Acker heard that night was that these prized recordings—which would come to be known as “the Betty Boards”—had been broken up into three lots at auction and purchased by three different buyers.

In other words, a vast collection of some of the Dead’s finest work was essentially missing—sacred texts, just out there in the wind.

And then Acker put it out of his head. Until four years later, when he got a call from Carter: Betty Cantor-Jackson, his friend told him, needed some legal advice. Maybe Acker—his fellow Deadhead and now-successful lawyer—could help.

When Cantor-Jackson rang Acker in October 2011, he was at his desk in the Chicago-area offices of Storino, Ramello & Durkin, where he focuses on municipal law. She was vexed: The Dead had just released a special live box set from their 1972 European tour, which she had mixed, and she was not being compensated. Acker immediately called his buddy Jeff Butler—Acker’s good friend and law school classmate who had also been in the trailer that night—and started talking about making arrangements to go to California and meet with Cantor-Jackson in person.

Over the next few months, Acker and Carter called on a network of Denison alumni for support. The first meeting with Cantor-Jackson—a sprawling, friendly deposition meant to establish her copyright—took place in the Tiburon, California, home of Curt Himy ’88. Acker also hit up the Denison network for more legal advice, his friend Jim Willson ’76 eventually connecting with John Kanberg ’79 in San Francisco, who set Acker up with one of the country’s top intellectual property lawyers. When Acker met with Betty again in May 2012 to iron out a consulting agreement, the location was again sourced via another Denison connection, this time a musician Acker knew through his senior-year roommate, Peter Brooke ’83.

Eventually, the loose consortium of interested parties—Acker, Butler, and Carter, as well as another of Acker’s friends from law school, Chuck Dadswell—formed the legal entity, ABCD (using the first letter of each member’s last name). The goal of ABCD was to help Cantor-Jackson in her battle to recover royalties—hopefully by purchasing the lost lots of her recordings, should they ever turn up.

That would serve Acker, Carter, and Butler’s ultimate goal: Getting the missing music to the masses.

Then, in June 2012, there was news: One of the buyers of the storage auction tapes was in dire financial straits and wanted to sell. And so began the quest to recover the Betty Boards.

“Dude, you’re not going to believe this. This guy has got goats galore. They’re all over.”

That was Dadswell and Butler’s initial report back from the meeting with the buyer of one of the Betty Boards auction lots. Inside, goats, live goats, were on the furniture—the couches, the tables, the beds. And alas, the tapes had not been kept in good condition, with some covered in mold—or worse.

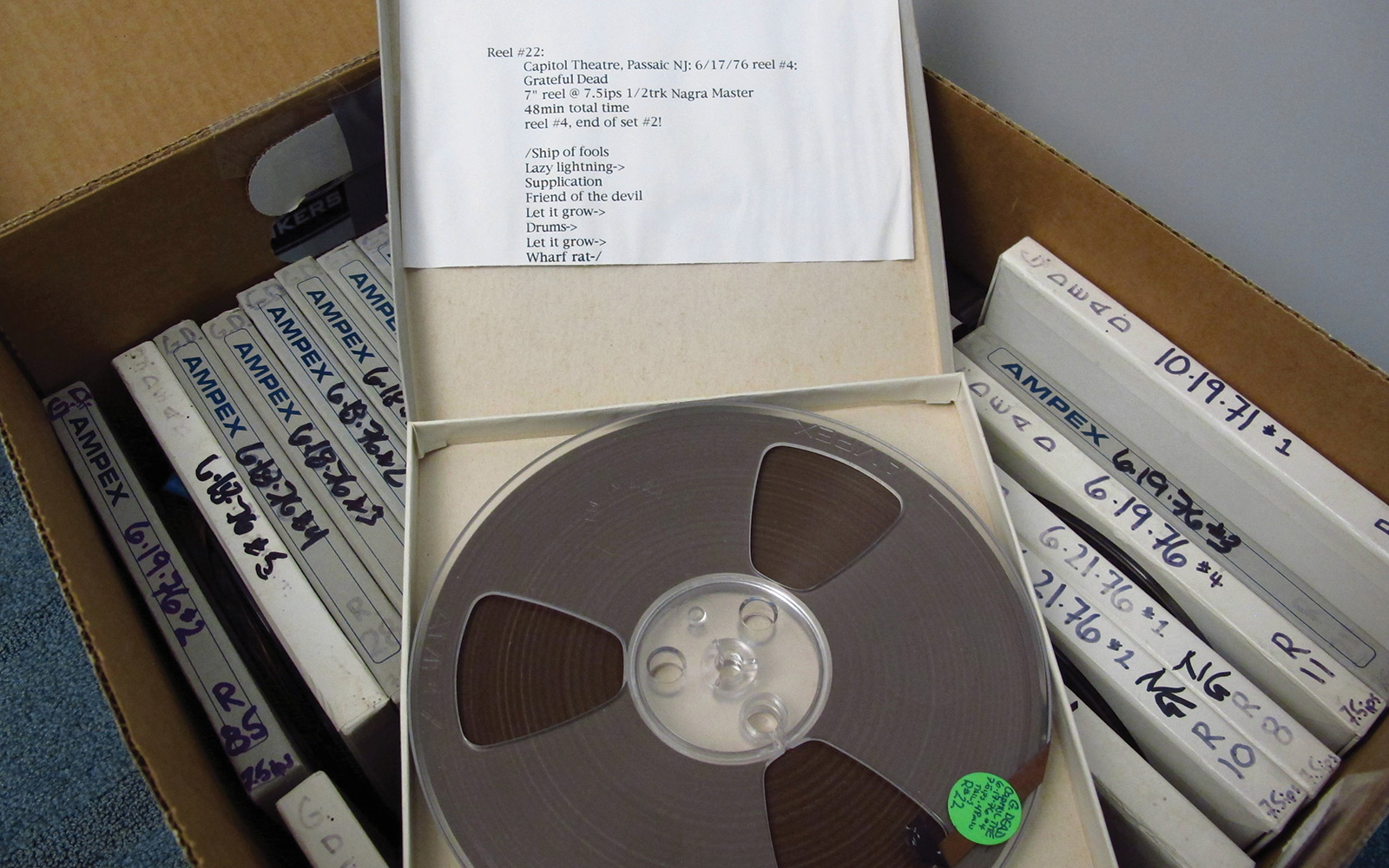

But what wasn’t destroyed was remarkable. And so, a few months later, the newly formed ABCD group drew up the legal forms and funded a purchase for about 260 reels. Butler and Dadswell picked up all of the tapes from the goat man’s house and sent them off to be cleaned and restored. Once they were tidied up, Acker, Butler, and Beck Fisher spent a long Sunday night in a Denver, Colorado, storage unit, inventorying the reels and packing them up in Tupperware containers, Fisher snapping photos for posterity. It was a long night that turned into an early morning, with Acker growing increasingly ill from whatever uncommon detritus the reels had picked up from the goat man’s house.

But it was a victory. One set of sacred texts had been saved.

“We’d use the concerts as connection points ... We socialized around what we understood as the idyllic time of our lives from college.”

The other two caches of Betty Boards, though, were still missing. But the Dead live bootleg community is tight, and with the word out that ABCD was on the hunt for the lost reels, two other buyers soon surfaced.

As travel to the West Coast increased for meetings with sellers and record executives, the ABCD crew would again require local support—and offering help were John Kanberg in San Francisco and Charlie Baker ’89 in Los Angeles. Baker would provide overnight housing as well as a garage where the crew could catalog any purchases. This kind of help on the road was incredibly valuable, Acker says: All told, ABCD estimates that they spent 1,500 hours in travel time and legal work on the project. The commitment paid off: In October of 2014, one of the other Betty Board auction buyers agreed to sell to ABCD. The lot was a massive haul, totaling some 520 reels stacked in tall rows of banker boxes and Tupperware containers, with ABCD funding the purchase and putting together all of the legal paperwork. In February 2014, the owner of the third and final lot—this one 120 reels—reached out to ABCD through the Deadhead community; ABCD bought those too.

Among those two massive troves of Betty Boards—which had been pristinely kept in goat-free locations—was perhaps the most famous Dead show of all time: The Dead at Barton Hall, Cornell University, May 8, 1977. (Editor’s note: The author wore out his copy in college.) It was the Dead at the height of their powers, and a foundational piece in any collection. “[I]t’s fair to conclude that Cornell ’77 is one of—if not the—most listened to Dead show of all time,” writes Peter Conners in Cornell ’77: The Music, the Myth, and the Magnificence of the Grateful Dead’s Concert at Barton Hall. In 2011, the Library of Congress selected the show for induction into its National Recording Registry—meant for recordings that are “culturally, historically or aesthetically important, and/or inform or reflect life in the United States.”

Now ABCD had a version of that show mixed by a woman known for her meticulous ear and in sparklingly clear quality. In other words, it is perhaps the most sacred of all the Dead’s sacred texts. And it was now, finally, in safe hands.

The path from raw reels to wider distribution got a bit rocky. There were some tough negotiations and moments when everyone involved became a bit disillusioned by the business realities of the music industry. But in the end, ABCD sold about 375 reels (with an estimated 400 hours of recordings) to the Dead’s record company—just breaking even on their purchases and restoration costs. Acker and Butler drove the reels to Burbank for final delivery in November 2016. And while ABCD couldn’t get

Cantor-Jackson direct renumeration, it did give her back all of her original recordings of non-Dead acts like the Jerry Garcia Band and New Riders of the Purple Sage that they had recovered, which had great personal value to her.

With that, ABCD’s six-year saga of the Betty Boards recovery was over.

And true to Acker and Carter’s original mission, the music is indeed making its way to the masses. The Dead has already released almost 20 of the shows that ABCD recovered. “That’s what it’s all about,” Carter says. “I’m listening to one of the shows right now. Just came in the mail.” It’s February, and the Dead have just released a special, limited edition of a show from February 26, 1977, in San Bernardino. “This is a tape that Andy and I recovered, and the Dead just released it.”

There’s even a little shout-out on the packaging’s liner notes, says Carter, that says, “Thanks to ABCD.” “Nobody knows who ABCD is,” he says. “My name’s not anywhere on this—and we did that on purpose, because it’s Betty’s music.”

Beck Fisher got one of the limited releases too, and he’s looking forward to the next round of Betty Boards. “All these new tapes are coming out that were supplied by Acker and Rob and Prescott and those guys,” he says. “And they are just incredible, incredible shows,” he says. But this new San Bernardino release is particularly meaningful. “We used to listen to that show back in the Denison days,” he says with a laugh. “Yeah, that was in heavy rotation in 1984.”