Udo Schlick has just approached two employees of the Kentucky Science Center carrying a human spleen in one hand and a kidney in the other. He holds them out for takers. “This just got real,” says Mark Sieckman, manager of executive initiatives. He and Brittney Gorter, the senior manager of marketing and sales, are turning the organs over in their hands. Weighing them. Staring at them. They’re a little grossed out. Or they’re just in awe. It’s hard to tell. As for Schlick? He’s clearly enjoying this.

These are “touchable specimens,” he tells Gorter, a rare find in the BODY WORLDS exhibit that Schlick and his team from Germany are installing at the Science Center for a five-month run. The rest of the specimens—a brain over here, a diseased lung lying next to its healthy counterpart, a skeleton propped in the corner with his face toward the wall as if he had been caught talking in class—will not, by any means, be “touchable.” As the day plods on, they will be carefully unwrapped and encased in glass with accompanying fun facts. “20 cigarettes a day produce five fluid ounces of tar, the equivalent of a cup of coffee,” reads one. Another: “Every minute, 1.5 gallons of air passes through the lungs.”

Schlick is whistling.

This is one of several exhibitions from the BODY WORLDS company making their way around the globe. Each one tends to come with a lot of community chatter, because while the brains and the spleens and the hearts are wild enough, the main features are the whole bodies on display. They’ve been dissected down to muscle and bone and then preserved using plastination, a complicated technique that involves removing water and fat from the body and replacing it with specialized polymers. The process was developed at the University of Heidelberg’s Institute of Anatomy back in 1977 by Gunther von Hagens, the anatomist who created BODY WORLDS.

He was the first to display bodies in such a way, but many companies followed, including some whose methods of body procurement were in question. (BODY WORLDS’ specimens all come from the Institute for Plastination, also founded by von Hagens, which currently boasts 13,000 willing donors on its roster.)

The exhibition, called Vital, that’s being set up now in Kentucky, exposes the realities of human health—hence the smoker’s lung and the full digestive system stretched out in a vertical display, but it’s not all about the nasty things that we put our bodies through. It’s about the beauty of fitness and movement.

Tucked into a back corner, the first full body exhibit is already in place. A man, carved down to muscle, holds a female acrobat in the air. Male and female flamenco dancers—positioned in traditional flamenco stances—will make their debut in the main gallery. A man with a lasso will appear later. So will a fencer. The bodies are there, stripped to the barest bare one can be. And they are unabashedly controlling the entire room.

Joanna Haas ’89, executive director of the Kentucky Science Center, hasn’t had her coffee yet, and it’s imperative that caffeine kick off her to-do list this morning. She’s a single mom to a 7-year-old boy named Winston, so she spends her early mornings packing lunches and shuttling him to school before making her way into the office, where today, there’s a lot going on. Giant black crates are being wheeled in and out of the center, bodies are being erected all over the place, and she’s got a board member on the way to walk through the gala presentation, which takes place in just two days and kicks off the bodies’ four-month stay in her facility. In the next 48 hours, the bodies all will be secured behind glass, the carpets will be cleaned, and Haas will be decked out in a pants suit with ruffles—a rare look for the woman with the short pixie haircut who currently is sipping black coffee in cords, hiking shoes, and a fleece vest. This is just the kind of work attire Haas had hoped for, even back at Denison when she stepped into the career services office for advice. “The director didn’t know what to do with me,” says Haas. No suits, Haas had told her. No 9-to-5 hours. They were pretty bold statements for a Vail Scholar, who dropped art to pursue psychology, and who was about to be let loose on the world with a shiny new degree and no job.

Even so, Haas found her way to COSI (Center of Science & Industry) in Columbus after graduation. She landed a position as a program director, and over the course of 10 years held a series of vice presidential positions in education and operations. She opened a consulting business and headed to Dearborn, Mich., where she worked for the Ford Motor Company and as director of the Henry Ford Museum & IMAX Theatre. By 2003, she was the director of the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh and within six more years she had made the trek back to her native Kentucky to take on her current role.

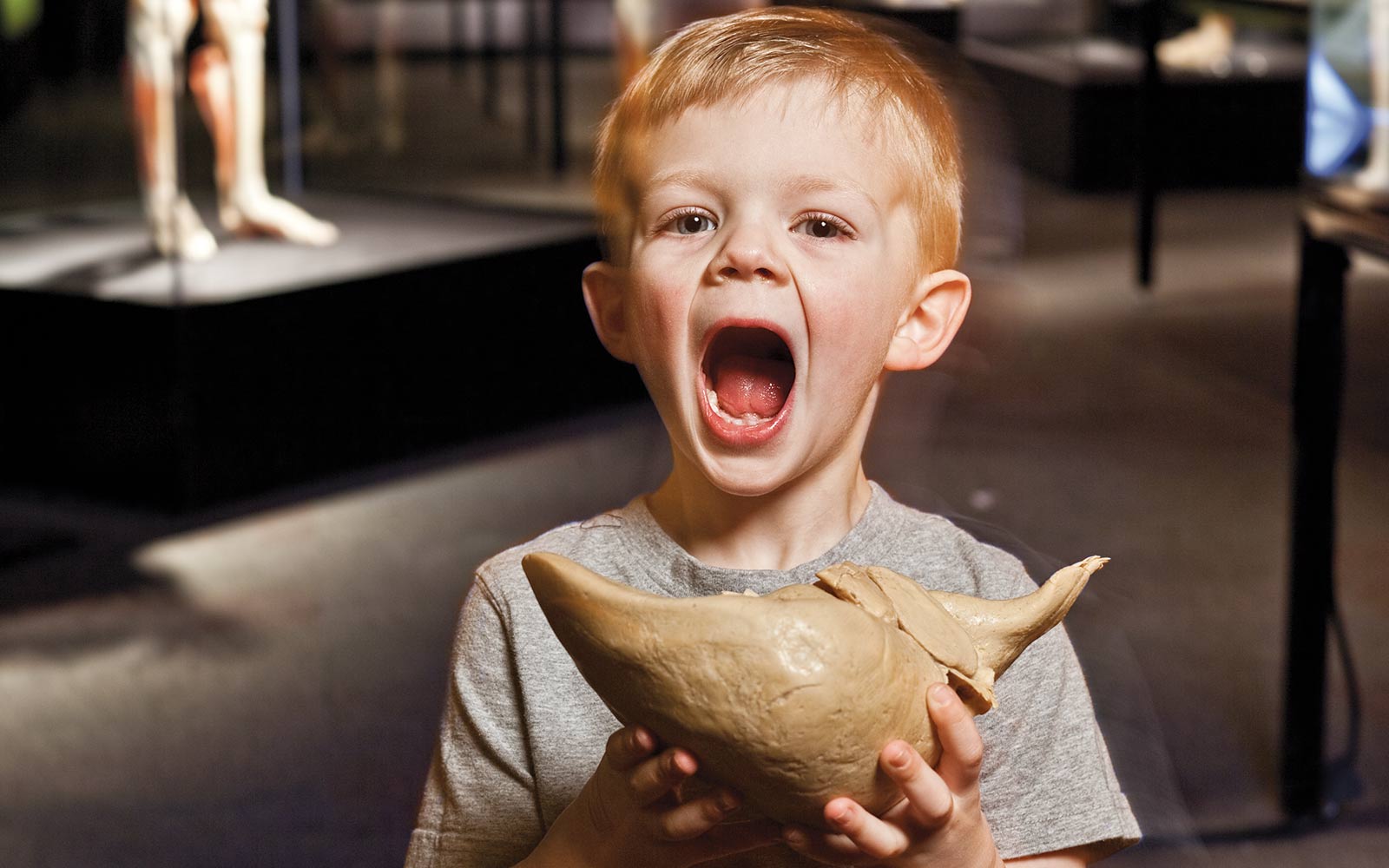

Today she’s walking through the Science Center soon after the doors have opened to the public. She’s greeting her staff, asking what field trips might be coming through, and discreetly pointing out a child who has hidden from his mother in one of the play areas. For Haas, her hope is that the patrons of the Science Center, especially the youngest ones, leave with a sense of curiosity and wonder that will propel them to continue learning, creating, and exploring, especially when it comes to the sciences. “You might hear how important it is for children to have free access to creative materials,” says Haas. “I’m always surprised when that’s not followed by making sure children have access to science and tools.” Anthony “Bud” Rock, CEO of the Association of Science-Technology Centers (for which Haas serves on the board of directors), points to the statistics on the nation’s children when it comes to science and math. “While we would all like to see them stronger,” says Rock, “those stats don’t take into account the value of inspiration that the sciences can offer and how that inspiration leads to creativity and entrepreneurship.”

Haas’ own home is, as she puts it, “an explosion of rulers and test tubes.” There are PVC pipes in the bathtub that Winston uses to build racecar roller coasters. The Haas family also keeps boxes and boxes of sticks, pine cones, and leaves. They’ve got another one full of locust shells. Winston is a constant creator and an intrepid explorer, traits that Haas encourages at every turn. “Adults are reticent to put a magnifying glass or a microscope in the hands of a tiny person,” says Haas. “Under supervision, they are capable of using those tools. … Woe is the child who doesn’t have a microscope.”

In everything from exhibits like Science in Play, with its hands-on activities for the youngest guests, to mentoring experiences for teenagers (last year, Louisville teens put in more than 7,000 hours of volunteer service), the Science Center aims to be a fun interactive experience that jump-starts curiosity and bolsters the local community by highlighting its strengths and educating its kids. “Kids can be some of our best science learners,” says Haas. “Uninhibited. Completely open to all possible things.”

It’s this demographic that science centers around the world hope to engage early and often. “The young people we capture before 8th grade are three times more likely to pursue science-related academics,” says Rock, citing a study conducted by Robert Tai of the University of Virginia. But the Kentucky Science Center is about education for all ages, really. That includes kids like Winston experimenting with sand and magnifying glasses in the children’s center as well as parents and grandparents who will tour the BODY WORLDS exhibit later this week to see—many for the first time—the inner workings of the human body. Winston will see the exhibition, too. His mom is the kind of mom who tells it like it is, never subbing cutesy names for anatomical parts, and certainly not shielding him from one of the most fascinating things in the universe: the human body.

Joanna Haas ’89, executive director of the Kentucky Science Center, hasn’t had her coffee yet, and it’s imperative that caffeine kick off her to-do list this morning. She’s a single mom to a 7-year-old boy named Winston, so she spends her early mornings packing lunches and shuttling him to school before making her way into the office, where today, there’s a lot going on. Giant black crates are being wheeled in and out of the center, bodies are being erected all over the place, and she’s got a board member on the way to walk through the gala presentation, which takes place in just two days and kicks off the bodies’ four-month stay in her facility. In the next 48 hours, the bodies all will be secured behind glass, the carpets will be cleaned, and Haas will be decked out in a pants suit with ruffles—a rare look for the woman with the short pixie haircut who currently is sipping black coffee in cords, hiking shoes, and a fleece vest. This is just the kind of work attire Haas had hoped for, even back at Denison when she stepped into the career services office for advice. “The director didn’t know what to do with me,” says Haas. No suits, Haas had told her. No 9-to-5 hours. They were pretty bold statements for a Vail Scholar, who dropped art to pursue psychology, and who was about to be let loose on the world with a shiny new degree and no job.

Even so, Haas found her way to COSI (Center of Science & Industry) in Columbus after graduation. She landed a position as a program director, and over the course of 10 years held a series of vice presidential positions in education and operations. She opened a consulting business and headed to Dearborn, Mich., where she worked for the Ford Motor Company and as director of the Henry Ford Museum & IMAX Theatre. By 2003, she was the director of the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh and within six more years she had made the trek back to her native Kentucky to take on her current role.

Today she’s walking through the Science Center soon after the doors have opened to the public. She’s greeting her staff, asking what field trips might be coming through, and discreetly pointing out a child who has hidden from his mother in one of the play areas. For Haas, her hope is that the patrons of the Science Center, especially the youngest ones, leave with a sense of curiosity and wonder that will propel them to continue learning, creating, and exploring, especially when it comes to the sciences. “You might hear how important it is for children to have free access to creative materials,” says Haas. “I’m always surprised when that’s not followed by making sure children have access to science and tools.” Anthony “Bud” Rock, CEO of the Association of Science-Technology Centers (for which Haas serves on the board of directors), points to the statistics on the nation’s children when it comes to science and math. “While we would all like to see them stronger,” says Rock, “those stats don’t take into account the value of inspiration that the sciences can offer and how that inspiration leads to creativity and entrepreneurship.”

Haas’ own home is, as she puts it, “an explosion of rulers and test tubes.” There are PVC pipes in the bathtub that Winston uses to build racecar roller coasters. The Haas family also keeps boxes and boxes of sticks, pine cones, and leaves. They’ve got another one full of locust shells. Winston is a constant creator and an intrepid explorer, traits that Haas encourages at every turn. “Adults are reticent to put a magnifying glass or a microscope in the hands of a tiny person,” says Haas. “Under supervision, they are capable of using those tools. … Woe is the child who doesn’t have a microscope.”

In everything from exhibits like Science in Play, with its hands-on activities for the youngest guests, to mentoring experiences for teenagers (last year, Louisville teens put in more than 7,000 hours of volunteer service), the Science Center aims to be a fun interactive experience that jump-starts curiosity and bolsters the local community by highlighting its strengths and educating its kids. “Kids can be some of our best science learners,” says Haas. “Uninhibited. Completely open to all possible things.”

It’s this demographic that science centers around the world hope to engage early and often. “The young people we capture before 8th grade are three times more likely to pursue science-related academics,” says Rock, citing a study conducted by Robert Tai of the University of Virginia. But the Kentucky Science Center is about education for all ages, really. That includes kids like Winston experimenting with sand and magnifying glasses in the children’s center as well as parents and grandparents who will tour the BODY WORLDS exhibit later this week to see—many for the first time—the inner workings of the human body. Winston will see the exhibition, too. His mom is the kind of mom who tells it like it is, never subbing cutesy names for anatomical parts, and certainly not shielding him from one of the most fascinating things in the universe: the human body.

As Haas practices her speech for BODY WORLDS’ opening night, she stands on the stairs in the Science Center taking mental notes on what she’ll say to the crowd when they arrive for the big event. She’ll need to introduce a few folks, which won’t be a problem—she’s more worried about thanking the sponsors. There are a lot of them, and she doesn’t want to miss anyone, especially at this moment, when she and her team are about to open the doors on two-plus years of planning and negotiating and publicizing. She doesn’t seem nervous, just ready to get this thing going. Haas will be fine in front of the crowd. She’s done this before in Columbus and Michigan and Pittsburgh, and she’s the kind of director who can chat with the media or a big donor without a stumble or a gaffe. The Science Center’s PR person often lets Haas simply run with an interview instead of coaching her along.

In two nights the board will be here. As will community members who have paid between $100 and $250 per ticket to be the first to glimpse the exhibit. There will be cocktails and hors d’oeuvres and valet parking. Haas wants her guests to be wowed, certainly, but not necessarily by the VIP treatment or the aerial dancers who have been hired to perform. She wants to inspire in these first guests the same reaction she wants to elicit from Winston and the children and everyday visitors who make their way to the Kentucky Science Center. It all comes back to that sense of wonder. She knows that no one is coming here for in-depth lessons in science, but she hopes that when they have seen the BODY WORLDS exhibit they will leave curious to know more. She hopes they come and look at the human body in a new way. Maybe in the way that Mark Sieckman and Brittney Gorter looked at the human spleen and kidney they were able to hold while doing their day jobs. Or maybe in the way that Udo Schlick, the former dissector turned exhibition-installer, looks at the specimens he’s come to know so well, one of which won’t be on display in Kentucky. She’s part of another exhibit in another city, but she’s his favorite: a ballerina, positioned sitting back on one knee in a full curtsy.

The burly German dressed all in black demonstrates, stretching his arms out to either side, tucking one leg behind the other, and bowing with grace. “It’s really good,” he says. “She looks very pretty.”

Haas is walking along Main Street in Louisville when she spots a plastic bag dancing along the sidewalk. She stoops to pick it up and tosses it into a nearby trashcan as she makes her way back to the Center after lunch. This whole city is her office. She meets donors for dinner across the street at 21C, a high-end restaurant, hotel, and art gallery. She partners with local businesses and schools to create interactive classes for grades K-8 that tackle the planet and the universe, along with biology and biodiversity. And that’s not to mention the hands-on labs for grades 6-12 in robotics, physics, and chemistry, or the indispensable basic training in using a microscope to study cells, particles, and organisms.

The Kentucky Science Center sits on West Main Street in the heart of the city, but it hasn’t always been there. The street itself is a bit of a Cinderella story, says Haas. In the ’70s the area had become dilapidated and was taking on the aura of a ghost town. Run-down buildings with broken windows weren’t a likely destination for city-dwellers or tourists. The area needed a makeover in a major way, so the city’s leadership created what is now known as Museum Row, first by relocating the science center (then known as the Museum of Natural History and Science) from its home at Fifth and York across town to West Main. At the same time, Actors Theater was settled on the opposite end of Main Street. Other organizations, like the Kentucky Center for the Arts and the Louisville Slugger Museum followed. Today Main Street is home to seven museums, two performing art institutes, coffee shops, restaurants, and galleries. “It’s an awesome cultural mecca,” says Haas. And she’s glad to be a part of that. Glad that people are streaming in to access the arts and the sciences in ways they hadn’t just a few decades ago. She’s glad that Winston will have access to this area as he grows up.

To Haas, the Science Center and all of its neighbors have an important role to play in their communities, a role that has evolved in the last 20 years.

There was a time, Haas points out, that the idea of an interactive museum experience was unheard of—“the notion that you could come to a museum and, instead of looking at an artifact, engage in hands-on learning,” she says. But then the Exploratorium in San Francisco started doing it. And COSI started doing it. And the Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh started doing it. And the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago started doing it. And guests opened their wallets and became members and made donations to keep it all going.

In the 1990s, the Kentucky Science Center (then called the Louisville Science Center) picked up the wave and began to branch out, incorporating new exhibits and educational components. In the 1970s, a hands-on, interactive exhibit on a human cell, for example, might have consisted of an image of a live cell, with buttons that, when pushed, would offer an explanation of different parts of the cell, says Bud Rock. These days a science center might start with a look at infectious diseases and that might lead to a discussion of the human body, and that, in turn, might lead to the role of the cell. The broader perspective, he says, gives science context and relevance and allows visitors to explore issues that are important to them in their local and global communities.

The BODY WORLDS exhibition, for example, won’t just open in two days, collect money to shuffle people past glass cases for four months, and then pack up and ship out. The bodies are actually part of a larger program. “We have set up this exhibit to serve as a catalyst for community conversation about important health issues facing Kentuckians,” says Haas. She points out that some of Louisville’s economic drivers are in the worlds of healthcare, medicine, and aging care, but she also points out that the region often ranks low when it comes to the health of its citizens. “It’s a well-known fact that Kentuckians are some of the least healthy adults—and children—nationwide,” she says. So Louisville has great resources, but it also has great need. “The science center, through programming like BODY WORLDS,” she says, “is responding to that confluence.” To do that, the center’s team members enhanced the BODY WORLDS experience by bringing together an array of partners to engage visitors on every level. Medical professionals and aspiring medical students talk with visitors in the gallery. A fleet of adult programs has been put into action, including lectures and dialogue events with medical experts in the areas of brain health, cardiology, women’s health, organ transplantation, and cancer. One space in the center is alive with family fitness activities and nutrition education. And many health education partners have chosen to use BODY WORLDS as a public education platform for organ donation, heart health, cancer awareness, and more. “A science center is a reflection on a community, its economic drivers, its educational realities and needs,” says Haas. A center in Silicon Valley, she points out, would be vastly different from one in Pittsburgh. And from this one in Kentucky, for that matter.

As Haas practices her speech for BODY WORLDS’ opening night, she stands on the stairs in the Science Center taking mental notes on what she’ll say to the crowd when they arrive for the big event. She’ll need to introduce a few folks, which won’t be a problem—she’s more worried about thanking the sponsors. There are a lot of them, and she doesn’t want to miss anyone, especially at this moment, when she and her team are about to open the doors on two-plus years of planning and negotiating and publicizing. She doesn’t seem nervous, just ready to get this thing going. Haas will be fine in front of the crowd. She’s done this before in Columbus and Michigan and Pittsburgh, and she’s the kind of director who can chat with the media or a big donor without a stumble or a gaffe. The Science Center’s PR person often lets Haas simply run with an interview instead of coaching her along.

In two nights the board will be here. As will community members who have paid between $100 and $250 per ticket to be the first to glimpse the exhibit. There will be cocktails and hors d’oeuvres and valet parking. Haas wants her guests to be wowed, certainly, but not necessarily by the VIP treatment or the aerial dancers who have been hired to perform. She wants to inspire in these first guests the same reaction she wants to elicit from Winston and the children and everyday visitors who make their way to the Kentucky Science Center. It all comes back to that sense of wonder. She knows that no one is coming here for in-depth lessons in science, but she hopes that when they have seen the BODY WORLDS exhibit they will leave curious to know more. She hopes they come and look at the human body in a new way. Maybe in the way that Mark Sieckman and Brittney Gorter looked at the human spleen and kidney they were able to hold while doing their day jobs. Or maybe in the way that Udo Schlick, the former dissector turned exhibition-installer, looks at the specimens he’s come to know so well, one of which won’t be on display in Kentucky. She’s part of another exhibit in another city, but she’s his favorite: a ballerina, positioned sitting back on one knee in a full curtsy.

The burly German dressed all in black demonstrates, stretching his arms out to either side, tucking one leg behind the other, and bowing with grace. “It’s really good,” he says. “She looks very pretty.”