There are a lot of debates swirling about the value of higher education these days. If you’re looking for a stimulating discussion, you could do worse than wade into the ongoing national conversation over the current state and future direction of American higher education. Private or public? Four-year or two-year? In-class or online?

But if it’s a real debate you’re after, look no further than the roiling argument over the value of one particular kind of college or university education: the kind offered by Denison. The temperature of that debate was neatly summed up in the headline of an article that appeared last October on the website of the Public Broadcasting Corporation: “Is a Liberal Arts Degree Worth It?”

The arguments of those who answer that question with a resounding “no” can be reduced to two basic, and not entirely unrelated, positions:

a) a liberal arts degree is too expensive, and

b) a liberal arts degree won’t help you land a job.

Both arguments are compelling, especially when times are tough. With unemployment high and the future of the economy uncertain, students—and their parents—are more concerned than ever about the practical value of the degrees for which they are paying. And paying quite a bit: $50,000 a year at top-tier private institutions like Denison, for a sticker price that after four years amounts to “roughly the median price of a home in some metropolitan areas,” as the editors of U.S. News & World Report noted in 2010. This in an era when student indebtedness is also on the rise: $25,250 per head, on average, for the national class of 2010, according to the Institute for College Access and Success, with figures approaching $50,000 at a number of individual schools. (By comparison, Denison students’ average debt is about $16,000—and more than half of the college’s graduates leave without any debt at all.)

But for those on the “yes” side of the question, the purely financial, can-you-get-a-job arguments are the easiest to counter. Studies consistently show that those who earn a bachelor’s degree also earn significantly more income over the course of their careers than those who do not. People with liberal arts degrees pursue all manner of careers; the National Science Foundation’s data show that the nation’s top liberal arts colleges outperform even large research institutions in producing graduates who go on to earn doctorates in science and engineering, two areas that will be in particularly high demand in the years to come. And many liberal arts colleges, Denison included, have robust internship programs designed to boost students’ career potential by giving them real-world, resumé-building experience. In addition, Denison’s Career Exploration and Development Center recently launched an externship program that will allow students to shadow alumni on the job. And while student indebtedness is a serious problem, the actual debt any individual student accrues has a lot to do with where she goes to school. According to Nancy Hoover, director of financial aid, Denison’s lower debt burden—about $9,000 less than the national average—is due to the fact that about 95 percent of Denison students receive some sort of financial aid from the college, either merit or need-based, or both. Denison’s Admissions Office recently awarded members of the incoming class of 2016 annual scholarships in the $10,000 to $40,000 range. “You can go to a good liberal arts college and not come out overloaded with debt,” says Provost Bradley Bateman, himself an economist.

But what about the merits of a liberal arts education that cannot be entirely reduced to numbers and dollar signs? Proponents of the liberal arts contend that a liberal education confers long-term benefits both in the workplace and in the realms of good citizenship and self-fulfillment. Such arguments are neither as colorful nor as easily summarized as purely quantitative ones, but they get at the heart of what makes liberal education unique. They also hinge on a couple of niggling questions, like: What exactly is a liberal education? And how, exactly, does one measure its true value?

Although the terms are used interchangeably, liberal education and the liberal arts are not entirely synonymous. The latter refers to a clutch of subjects that evolved out of the medieval university curriculum, which comprised the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and the quadrivium (math, geometry, music, and astronomy). The trivium, in turn, dates back to classical antiquity, when it was considered essential study for any free citizen— “liberal” deriving from the Latin liber for “free.”

But as the Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger pointed out in the first century C.E., the point of a liberal education has never been just to master a particular subject, as useful as it might be, but rather to develop the capacity for wisdom and virtue. A present-day exponent might put it this way: while the arts and science majors that a college like Denison offers are of considerable value in and of themselves, they remain, in the grand scheme of liberal education, a means rather than an end.

But a means to what? You don’t often hear words like “wisdom” and “virtue” bandied about in contemporary debates over higher education. Instead, those who argue most passionately in favor of liberal education talk about “cognitive and personal capacities,” to use the phrase favored by Robert Connor, senior adviser to the Teagle Foundation, a private philanthropy that seeks to improve student learning and engagement. (The foundation has awarded funds to Denison to improve academic assessment and gauge student improvement in areas such as critical and creative thinking.)

Connor believes that relying solely on quantitative measures, such as the number and cost of college degrees, is a mistake. Better, he argues, to pay more attention to issues of quality: the ability of an educational institution to nurture critical thinking, effective communication, moral reasoning, and lifelong learning—all of which, he believes, lie “very, very close to the core of what liberal education provides for students.” As it happens, all of those skills are also extremely helpful in navigating a rapidly changing, deeply interconnected global environment in which individuals are required to make sense of vast amounts of information and to learn new skills more or less constantly.

There are a lot of debates swirling about the value of higher education these days. If you’re looking for a stimulating discussion, you could do worse than wade into the ongoing national conversation over the current state and future direction of American higher education. Private or public? Four-year or two-year? In-class or online?

But if it’s a real debate you’re after, look no further than the roiling argument over the value of one particular kind of college or university education: the kind offered by Denison. The temperature of that debate was neatly summed up in the headline of an article that appeared last October on the website of the Public Broadcasting Corporation: “Is a Liberal Arts Degree Worth It?”

The arguments of those who answer that question with a resounding “no” can be reduced to two basic, and not entirely unrelated, positions:

a) a liberal arts degree is too expensive, and

b) a liberal arts degree won’t help you land a job.

Both arguments are compelling, especially when times are tough. With unemployment high and the future of the economy uncertain, students—and their parents—are more concerned than ever about the practical value of the degrees for which they are paying. And paying quite a bit: $50,000 a year at top-tier private institutions like Denison, for a sticker price that after four years amounts to “roughly the median price of a home in some metropolitan areas,” as the editors of U.S. News & World Report noted in 2010. This in an era when student indebtedness is also on the rise: $25,250 per head, on average, for the national class of 2010, according to the Institute for College Access and Success, with figures approaching $50,000 at a number of individual schools. (By comparison, Denison students’ average debt is about $16,000—and more than half of the college’s graduates leave without any debt at all.)

But for those on the “yes” side of the question, the purely financial, can-you-get-a-job arguments are the easiest to counter. Studies consistently show that those who earn a bachelor’s degree also earn significantly more income over the course of their careers than those who do not. People with liberal arts degrees pursue all manner of careers; the National Science Foundation’s data show that the nation’s top liberal arts colleges outperform even large research institutions in producing graduates who go on to earn doctorates in science and engineering, two areas that will be in particularly high demand in the years to come. And many liberal arts colleges, Denison included, have robust internship programs designed to boost students’ career potential by giving them real-world, resumé-building experience. In addition, Denison’s Career Exploration and Development Center recently launched an externship program that will allow students to shadow alumni on the job. And while student indebtedness is a serious problem, the actual debt any individual student accrues has a lot to do with where she goes to school. According to Nancy Hoover, director of financial aid, Denison’s lower debt burden—about $9,000 less than the national average—is due to the fact that about 95 percent of Denison students receive some sort of financial aid from the college, either merit or need-based, or both. Denison’s Admissions Office recently awarded members of the incoming class of 2016 annual scholarships in the $10,000 to $40,000 range. “You can go to a good liberal arts college and not come out overloaded with debt,” says Provost Bradley Bateman, himself an economist.

But what about the merits of a liberal arts education that cannot be entirely reduced to numbers and dollar signs? Proponents of the liberal arts contend that a liberal education confers long-term benefits both in the workplace and in the realms of good citizenship and self-fulfillment. Such arguments are neither as colorful nor as easily summarized as purely quantitative ones, but they get at the heart of what makes liberal education unique. They also hinge on a couple of niggling questions, like: What exactly is a liberal education? And how, exactly, does one measure its true value?

Although the terms are used interchangeably, liberal education and the liberal arts are not entirely synonymous. The latter refers to a clutch of subjects that evolved out of the medieval university curriculum, which comprised the trivium (grammar, rhetoric, logic) and the quadrivium (math, geometry, music, and astronomy). The trivium, in turn, dates back to classical antiquity, when it was considered essential study for any free citizen— “liberal” deriving from the Latin liber for “free.”

But as the Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger pointed out in the first century C.E., the point of a liberal education has never been just to master a particular subject, as useful as it might be, but rather to develop the capacity for wisdom and virtue. A present-day exponent might put it this way: while the arts and science majors that a college like Denison offers are of considerable value in and of themselves, they remain, in the grand scheme of liberal education, a means rather than an end.

But a means to what? You don’t often hear words like “wisdom” and “virtue” bandied about in contemporary debates over higher education. Instead, those who argue most passionately in favor of liberal education talk about “cognitive and personal capacities,” to use the phrase favored by Robert Connor, senior adviser to the Teagle Foundation, a private philanthropy that seeks to improve student learning and engagement. (The foundation has awarded funds to Denison to improve academic assessment and gauge student improvement in areas such as critical and creative thinking.)

Connor believes that relying solely on quantitative measures, such as the number and cost of college degrees, is a mistake. Better, he argues, to pay more attention to issues of quality: the ability of an educational institution to nurture critical thinking, effective communication, moral reasoning, and lifelong learning—all of which, he believes, lie “very, very close to the core of what liberal education provides for students.” As it happens, all of those skills are also extremely helpful in navigating a rapidly changing, deeply interconnected global environment in which individuals are required to make sense of vast amounts of information and to learn new skills more or less constantly.

If you want to get a sense of what that kind of omnidirectional intellectual and professional flexibility can look like in practice, consider Kyan Bishop ’97, senior analyst at the Federal Reserve Board and visual artist. Bishop, a self-professed math-and-science kid who was born in South Korea and has played piano since childhood, graduated with a double major in Spanish and economics and a minor in music. She also spent a year abroad in Chile, wrote her honors thesis on the socioeconomic impact of gypsy culture in Spain, and joined the Peace Corps after graduation, traveling to Paraguay to help an artisans’ cooperative balance its books and market its wares. Her interest in art piqued, Bishop took a ceramics class back in the States and proceeded to earn a degree in studio arts from Montgomery College in Maryland.

Since then, she has pursued two parallel careers. In one, she works on community and economic development initiatives at the nation’s central bank, informing national policy decisions on financial services that affect underserved communities. (She was recently promoted to director of such initiatives at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.) In the other career, she creates abstract sculpture and conceptual installation art that is shown in galleries across the country and in South Korea, teaches ceramics and sculpture, and participates in artist residencies from Vermont to Colorado. “I know that some people see these as really disparate fields,” Bishop says. “But I see a lot of connections.”

For example, she feels that much of her artwork is informed by notions of how communities change and how individuals are affected by their surroundings, while much of her work for the Federal Reserve focuses on how people interact economically, and on the importance of place. And the organic connection between her various activities will soon be reinforced: As program director for community and economic development at the Atlanta Fed, Bishop hopes to explore how culture and the arts can act as economic drivers. “I will be overseeing staff who work in cities like Nashville, New Orleans, and Miami—really interesting places that have a unique cultural heritage,” she says. That, in turn, may give her the opportunity “to think of the prosperity of these communities as it relates to the arts and cultural integration.”

Of course, it is possible to sail through a four-year degree without developing the capacities and competencies that Connor talks about and that Bishop embodies. The sociologists Richard Arum, at New York University, and Josipa Roksa, at the University of Virginia, tracked assessment data for 2,300 students at a range of four-year colleges and universities and found that a large number made little progress on tests of critical thinking, complex reasoning, and writing. These findings are consistent with the National Survey of Student Engagement published by the Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research, which indicates that many college and university students spend relatively little time studying or writing. “How much are students actually learning in contemporary higher education? The answer for many undergraduates, we have concluded, is not much,” Arum and Roksa wrote in their book, Academically Adrift: Limited Learning on College Campuses. Rather, many appeared to be “drifting through college without a clear sense of purpose.”

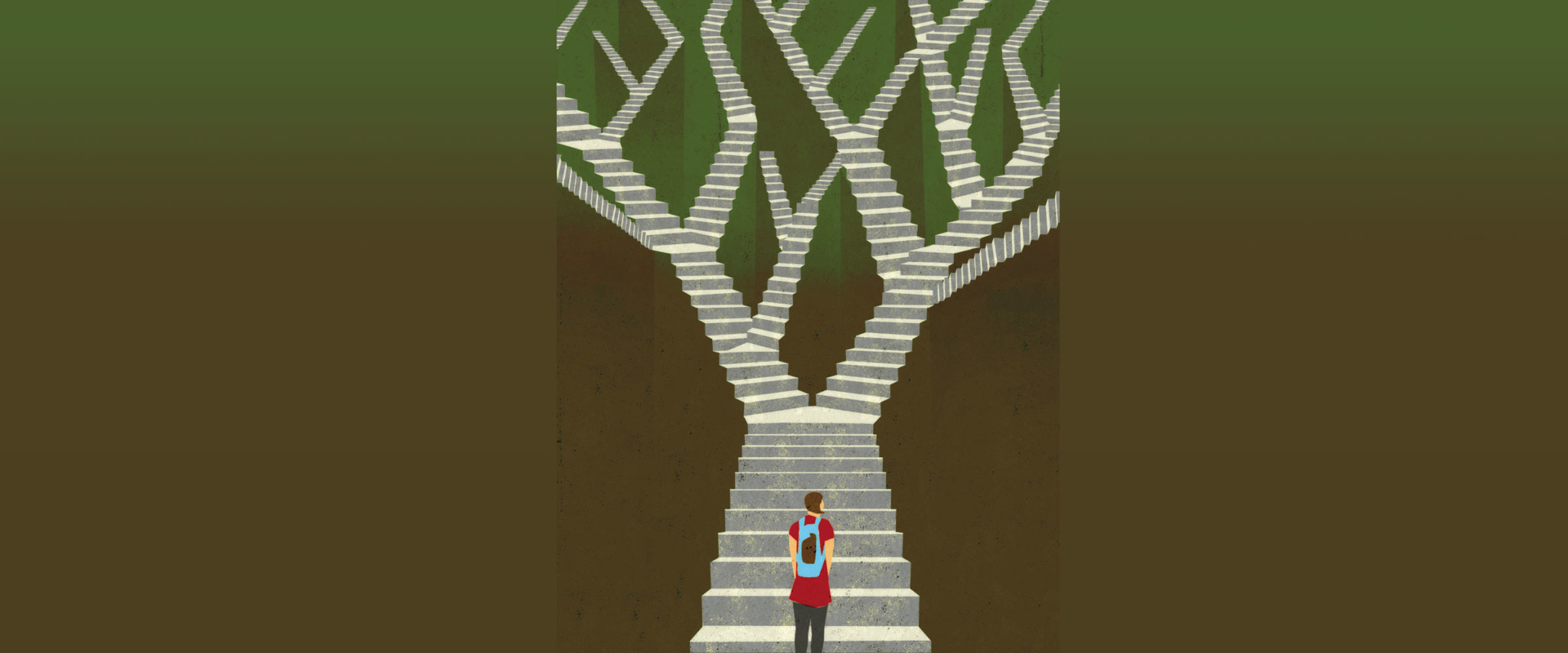

This may be a particular challenge for those pursuing liberal arts degrees. While the breadth of a typical liberal arts program is one of its greatest strengths, it also presents a potential pitfall: without careful guidance, students risk dabbling in this or that without ever developing a clear sense of purpose or a coherent set of skills.

Yet research also suggests that a handful of practices can help students get the most out of a liberal arts degree. According to the Wabash National Study of Liberal Arts Education, for example, students in residential undergraduate programs like Denison’s do best when confronted with “high-quality interactions with faculty,” “meaningful interactions with diverse peers,” and “deep learning”—i.e., the kind that requires students to pull together material and perspectives from different disciplines, to construct coherent arguments, and to think critically about them. These are precisely the kinds of skills that Denison faculty and administrators aim to instill. And if alumni opinion is any gauge, they are succeeding.

In a randomized survey conducted several years ago, Denison asked alumni what they thought of their liberal arts education five, fifteen, and twenty-five years after graduation. At the five-year mark, some wished that they had taken a few more courses related to their first jobs. By the fifteen-year mark, however, they were grateful for the flexibility their educations had afforded them over the course of predictably unpredictable careers. And by the twenty-five-year mark, they were talking about how much their time at Denison had enriched their lives, making them more interested and interesting people.

Which is not to say that the benefits of a liberal education are exclusively long-term. Allie Jeffers ’14 admits that she didn’t even know what the liberal arts were when she chose to attend Denison. (This is not unusual; in a 2005 survey, the Association of American Colleges and Universities found that few college students had ever heard the term “liberal education.”) But she quickly found out. “You are purposely taking classes in a multitude of disciplines,” she says, adding that “you really get to figure out what you want to do, and then do it.”

That exposure to multiple subject areas, coupled with a solid grounding in a major (or two) and the traditional liberal emphasis on reasoning and communication skills, can lead to unusual, and unusually interesting, results—like Bishop, the piano-playing, Spanish-speaking, economist-cum-artist; or Jeffers, who is majoring in communication, studying Chinese, and working as a research assistant in the Political Science Department—all while applying for an internship in Columbus, hoping for a year abroad in China, and contemplating business or law school after graduation. “I feel like I have a lot of options,” says Jeffers.

The effect is compounded on a small residential campus where students are forced to rub shoulders with people whose backgrounds are often quite different from their own, and where the overall education is geared toward helping students connect what they learn in the classroom to what happens outside it—whether that happens to be in the residence halls, on an internship, or in a foreign country.

That kind of broad exposure to a wide array of people and life experiences, coupled with thoughtful guidance from experienced teachers, can help students figure out what they want to do with their lives. It can also lead to the development of what Seneca called virtue, and to what we today might call ethics, or integrity, or moral reasoning.

Or rather, we might call it those things if we talked about it at all. Which we don’t, at least for the most part; Denison’s mission statement calls for inspiring students to become “discerning moral agents” and advocates for “a firm belief in human dignity and compassion,” but these are not themes that commonly appear in discussions of higher education, liberal or otherwise. And that’s rather odd, when you consider how prominent a role ethics plays in the great events that shape our lives, from wars to financial crises.

“Think of the great scandals in our society, even in the last few years,” says President Knobel, a historian. “They have to do with lapses in ethical judgment.” At a residential liberal arts college like Denison, he adds, students don’t just have the opportunity “to study the principles of ethics or participation in democratic activity. You have the opportunity to live it, in the kind of community you build in the residence halls, and all of the other ways you engage with others.” As Charles Blaich, director of the Wabash study says, “There’s a lot of learning that takes place that has nothing to do with the classroom.”

“My experience at Denison was absolutely formative in a lot of different ways, both from an educational perspective, and also in terms of what happened outside of class,” says James Cowles ’77, chief operating officer, EMEA (Europe, Middle East, Africa) markets, at the multinational financial services giant Citigroup.

Cowles majored in economics, a subject he readily admits is important to a career in business or banking. But he contends that it was the breadth of his education, and the ability it gave him to apply modes of thought gleaned from one discipline to others, that have been most valuable to him in the long run.

“I would defy anyone in the business world, certainly in the banking industry, to understand what’s going on today without a good understanding of history and a good understanding of political science,” he offers by way of example. “How do you apply something you’ve learned in one area somewhere else? That’s how I define intelligence. And a liberal arts education helps you to do that.”

But he also underlines the value of the many beyond-the-classroom experiences that a school like Denison affords, such as participating in a wide variety of activities and learning how to engage with an eclectic mix of people. “That’s critical,” says Cowles, who played rugby, served as a student adviser, was a member of Sigma Chi, and was president of the Interfraternity Council. “It exposes you to a lot of group dynamics and gives you the opportunity to learn leadership skills and the ability to deal with people, which you’re going to use later on in life.”

Exposure to a broad range of people and ideas; habits of mind and ways of interacting with others that will last a lifetime; the ability to make sound ethical decisions; the opportunity to explore different interests and to find one’s passion—or passions. This is a compelling list that proponents of liberal education point to when they make the case for their particular brand of learning. And there would seem to be no denying the advantages they carry. There is, however, one caveat: for a liberal education to work, you’re never really done with it. Knobel, for example, is particularly gratified when students come back from internships “realizing they aren’t going to learn it all in college.”

“For a liberal educator, that’s music to our ears,” he says. “Because what we are trying to do is to prepare students to learn for a lifetime, and it’s great that they figured that out now.”

Alexander Gelfand is a freelance writer based in New York. He has written for The New York Times, the Chicago Tribune, and The Economist.