On a gray winter day, Doug Boyd ’92 is in Frankfort, Kentucky, the state’s compact capital city. He knows this place well—or at least, he knows what it used to be. He’s the director of the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky and author of the new book, Crawfish Bottom: Recovering a Lost Kentucky Community, which details the history of a 19th-century Frankfort neighborhood wiped out by 20th-century urban renewal. He heads downhill—north, away from tree-lined streets and handsome brick homes with bronze plaques that mark spots where great moments in Kentucky history took place. When he crosses the railroad tracks that border the historic downtown, he stops. Before urban renewal, “The contrast must have been great,” Boyd says. “We are literally on the other side of the tracks. In fact, some people attribute the phrase to this town.”

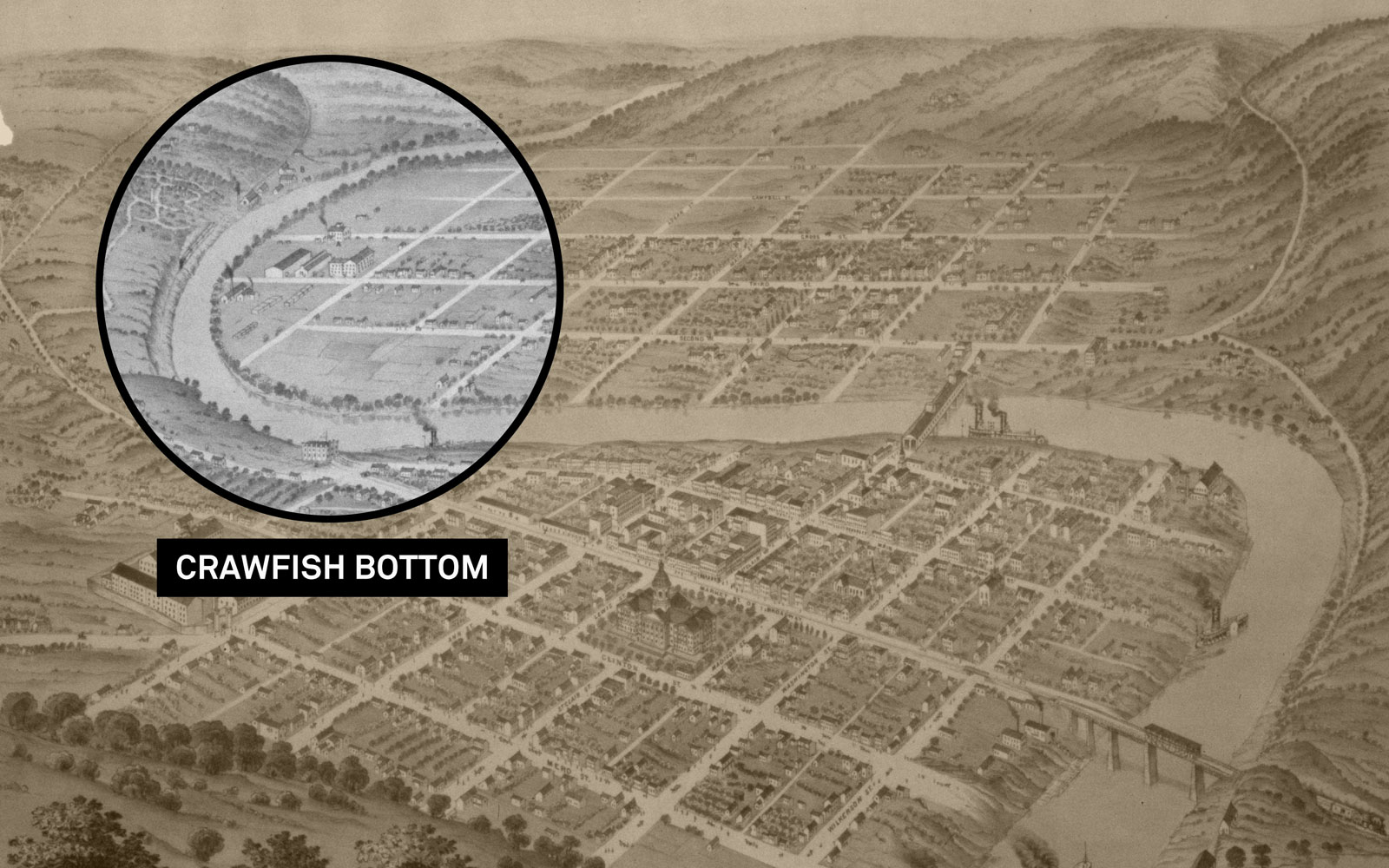

What’s on the other side of the tracks these days is the Capital Plaza Complex—a broad plaza, a slender office tower, a hotel and convention center, a YMCA, state office buildings, and a park tucked behind the levee that keeps the Kentucky River from sluicing through the streets when it floods. What used to be here, in this low land along the Kentucky River, was the community called Crawfish Bottom. The city began clearing the area for redevelopment in 1958—a long process that continued into the 1970s and ended when the last vestiges were replaced by the Kentucky Transportation Building in the 1990s. “Fifty acres were wiped out,” Boyd says, surveying the scene of concrete and glass. Wild tales about the raucous lives lived here have piqued the interest of Kentuckians for years. But there’s universality to that curiosity—or at least there should be, says Boyd. “Almost every city had a place like this and razed it.”

French dramatist Jean Cocteau once wrote that history is a combination of reality and fable. “The reality of history becomes a lie,” Cocteau said. “The unreality of the fable becomes the truth.” For Boyd, both the “reality” of the historical record and the “fables”—the memories of those who lived in a time and place, and the folklore about that place—are all important if you want to understand history. And that’s what he has tried to do in Crawfish Bottom. “This book is … about the process of balancing memory—the different tensions in creating the story that people came to know,” he says.

Crawfish Bottom was, in its time, a spot notorious for crime and poverty. That was a reputation that persisted long after the land was transformed by concrete and steel. But in 1991, Frankfort historian Jim Wallace located and interviewed former residents of the neighborhood. The oral histories that he collected painted a picture of a functional, tight-knit community that was broken apart—and never mended—by urban renewal. In his new book, Boyd has used those interviews, along with traditional historical sources, to create a deeper understanding of a complicated place.

What kind of a place was it? Wet, for one thing. Swampy enough that this part of the city was mostly vacant until after the Civil War, when free blacks, retreating from the Deep South, made their way to Frankfort and moved into wood frame houses that enterprising developers built on the cheap land. “There were not,” Boyd says, “a lot of other options for African-American people.” The state penitentiary was constructed here, too, attracting the families of incarcerated men, and many of the city’s German and Irish immigrants made the place home. The mix created something unique in the 19th century: a community where blacks and whites lived side by side. And it remained that way throughout its history.

That was one of the most tantalizing aspects of Crawfish Bottom for Jim Wallace as he did his interviews 20 years ago. Wallace, the assistant director of the Kentucky Historical Society, explains that “these people were outcasts. I wanted to get to the truth of what they were really like.” The project was a remarkable experience for Wallace, who grew up in the segregated South in the 1950s. “I did not shake the hand of an African-American person until I was 16 years old,” he says. Meeting elderly people who had lived in a community that had been integrated for generations was, he says, “a window for me into a whole different world.”

It was not always a tidy world. Vintage photographs show streets lined with houses set cheek-by-jowl—some shabby shotgun-style, some modest two-stories, most all wood, so fire was a constant problem. Sometimes it smelled, because the city’s gasworks were located here, away from the more refined parts of town. When the river rose, crayfish scuttled through the streets, giving residents an early warning that the sewers were about to heave up their contents. And whenever the river flooded, Crawfish Bottom felt the full weight of the disaster.

To outsiders, the neighborhood was synonymous with trouble from the first. There were saloons and the kind of violence that went with liquor. Loggers would bring their loads downriver to mills here, drinking and brawling before heading back to the Appalachian hills. The chaos repeated on county court days, when farmers and merchants would come to town. In 1884, Captain H.J. Hyde, the chief of police, singled out the neighborhood in his annual report to the mayor, complaining about drunkards carousing even on Sunday. South Frankfort, without a barroom, was “quiet as a prayer meeting in heaven,” he said. But “go visit Craw… and you will think there is a barbecue in hell.” Not surprisingly, the sex trade flourished. In 1880, the federal census included multiple addresses in Crawfish Bottom where the inhabitants willingly identified themselves as prostitutes. The city’s “working girls” came to include Lottie Brown, who once labored in the brothel of Belle Brezing, the infamous Lexington madam.

Boyd says he spent six months going through local newspapers from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, tracking the public accounts of life in the city’s lower quarter. “The only time this neighborhood made it into the historical record was when there was a flood, when there was crime, or when there was something that was offensive to someone else,” he says.

Generations of those reports cemented the violent, wanton reputation of “Craw”—the harsh nickname favored by the press. But together, Boyd’s research and Jim Wallace’s interviews with people who grew up there in the 1920s and ’30s paint a picture of a more complicated place, where well-ordered lives coexisted with less salubrious ones. Neighbors helped one another clean up after spring floods, and they checked on one another during summer heat waves. One of Wallace’s interviewees distinguished between what went on in the neighborhood at night and “everyday life”—the day-to-day concerns of working class folks. People Wallace spoke with generally acknowledged that the sex trade was—for better or worse—part of the fabric of the place. One black homemaker recalled two white prostitutes living and working near her home. “They brought their [customers] down in the black area because they knew they could not live what they were doing in the better area,” she said. “Long as they took care of their business it didn’t bother us none.” Besides, she said, “They were nice to children and everything.”

One nuance about “Craw” that outsiders—that is, white outsiders—failed to grasp, was that the neighborhood was an enclave for many members of the city’s African-American middle class. When the State Normal School for Colored Persons (today Kentucky State University) opened in 1887, Crawfish Bottom was where a lot of faculty settled. It was where the city’s African-American doctors had their offices, where the black barbers set out their striped poles, where two of the city’s largest black churches gathered their congregations, and where Jack Robb, Frankfort’s only African-American funeral director, served families in their grief. Whatever the larger city thought of the neighborhood, “If you were black, you had occasion to go to the Bottom,” says Sheila Mason. Mason grew up in South Frankfort, not the neighborhood that she calls “the Bottom.” But from 1954 to 1962 she went there each day to attend the city’s only public elementary school for black children, Mayo-Underwood School. Built in 1929 and named for two community leaders, the school loomed large in the memory of most everyone Wallace interviewed. And with good reason, says Mason. The all-black staff “understood family situations, understood economic situations. It was very nurturing.” It was an institution of the black community as a whole, she says, “one of the ties that bound it together.” Almost as beloved—and as symbolic—was the Tiger Inn. Located close to the school, the Tiger Inn offered inexpensive lunches for kids who didn’t pack a meal (the school cafeteria closed in the 1950s). After school, it was one of the few places where a black teen could take a date.

The desegregation of Frankfort schools meant the end of education at Mayo-Underwood. But by the time it closed in 1964, the die had already been cast for Crawfish Bottom’s future.

In 1955, a study revealed that nearly a quarter of the city’s arrests came from three blocks in the neighborhood; that half of the city’s VD cases lived there; and that the neighborhood represented only 2 percent of the city’s tax base. In 1956, a “Structure and Family Survey” by a city planning firm painted a picture of a place where too many houses lacked 20th-century rudiments like running water, heat, and indoor plumbing. They were, the report said, “mere shacks, built of flimsy scrap material which kept out neither rats … mice, nor misery.” The Frankfort Slum Clearance Agency was created to change all that.

One remarkable bonus of urban renewal: every property in Crawfish Bottom had to be photographed for appraisal purposes. Wallace found these photos in a moldering storage basement back when he was doing his interviews—a treasure trove of documents that captured history in black and white. Were there rat-infested shacks and tottering shotgun houses? Yes. But there were also streets of tidy duplexes and single-family homes. Wallace’s interviews preserve not only fond remembrances of that place but also the anger and profound loss residents felt at its destruction. Residents expected the community to be rebuilt: they expected to be able to return to a renewed Crawfish Bottom. Instead—with no well-thoughtout plan for relocation—the city scattered the residents. Businesses closed and institutions that had been central to many in the black community—beloved Mayo-Underwood school, the handsome American Legion Hall, the beautiful Corinthian Church with its majestic organ—were torn down. The physical neighborhood was gone, and so was the neighborliness that went with it. “These folks weren’t used to public housing,” Mason points out. Some were able to buy homes in other neighborhoods, she says, “but they had lost their community.”

If there’s one feature of Crawfish Bottom that time and Urban Renewal have failed to wipe from Frankfort’s psychic landscape, it’s the figure of John Fallis. Fallis was a moonshiner, a brawler, and a lothario; a businessman, a community leader, and a champion of the city’s poor. Violent, erratic, charming, compassionate—he was, says Boyd, “a symbol of the contradictions of the neighborhood.”

Born in 1879, Fallis moved with his parents to the neighborhood when he was a child, and he lived there all his life, except for brief service in the Spanish-American War—and those times when he was on the lam. For years he worked at a local distillery, learning a craft that would prove advantageous during Prohibition. By 1908, he’d left the distillery and was operating a grocery in the neighborhood, supporting a wife and family, and indulging his taste for attractive women. An early 20th-century picture of Fallis standing behind the counter of his store shows a handsome man—tall, lean, and muscular, with a sweeping handlebar mustache and dark, piercing eyes. He looks like a character from the HBO series Deadwood.

If Craw’s rough reputation in the outside world was shaped by newspaper accounts, so was Fallis’—and with good reason. Court records show a rap sheet filled with charges such as operating a still, perpetrating insurance fraud, “Cutting in Sudden Heat and Passion,” “Shooting and Wounding,” and “Intent to Kill without Killing.” Newspapers called him the “King of Craw,” and the drama of his life was fodder for their pages. In 1912, the press carried the story of his obliteration—how he’d apparently fallen while loading dynamite on his boat, causing an explosion that blew the boat to bits, leaving no sign of Fallis. Days later, the press recorded his return home and his cover story, that after the explosion he’d awoken, stunned, by the railroad tracks and had left town fearful that his clumsiness had killed others. In 1921, he shot and wounded three police officers, two bystanders, and his own child in a fight that began when police tried to arrest his teenage son. Fallis barricaded himself in his store, and in the melee that followed, the store burned and he escaped, turning himself in to authorities a week later. It was an epic captured in grainy photos on the pages of The State Journal. When he died in 1929—shot during a craps game while he was out on bail in a manslaughter case—it was the Journal’s banner headline.

But, as with other aspects of Craw, Fallis’ reputation in newsprint was only part of the story. Dave Fallis is his grandson—“My father was John’s bastard son,” Dave explains. “I never met the man. But I heard little bits about him throughout my childhood.” The “little bits” of family lore came into sharper focus in 1966 when Dave enrolled as a white student at Kentucky State University, a traditionally black college. Several elderly faculty members recognized his name and told him that his grandfather was highly respected in the black community. He paid for funerals, bought coal when families ran out of fuel, and extended credit when times were tough. A professor in the music department told Dave that she remembered going into his grandfather’s grocery with her mother as a child. “She said that when they didn’t have any money, Fallis would just run a tab,” he says. “But when they’d come back to pay the next week, somehow those bills kept disappearing.”

These good works may have been a means to an end. “The neighborhood was a voting precinct,” notes Boyd. Because Fallis was so highly regarded by his neighbors, “Politicians could count on him to deliver the vote.” Whatever the motivation for his philanthropy, it left a mark. Fallis’s name came up again and again as Jim Wallace conducted his interviews. The people he talked with were mostly African-American, and most were no more than children when Fallis died at the craps table. Even so, they knew the tales of his kindness as well as his crimes.

As Boyd reviewed Wallace’s interviews, examined newspaper accounts, and studied an unpublished biography written by one of his sons, it became clear that Fallis—buoyed by a combination of fact and lore—had taken on the stature of a folk hero. He’s an epic figure who would make a lively episode for History Detectives or Antiques Road Show—if, say, a Fallis great-grandchild possessed some intriguing artifact. Maybe the 1911 Colt revolver he failed to take to that fatal craps game, or the account ledger from the grocery store where so many debts were forgiven. Unfortunately, says Dave Fallis, “There’s nothing.” So Fallis, like Craw itself, depends on history’s retelling to live on.

Linda Vaccariello is the executive editor at Cincinnati Magazine.

Craw’s Storyteller

It shouldn’t have been surprising last fall when Doug Boyd found himself sitting in a jammed Frankfort, Kentucky, bookstore, signing copies of his new work. Kentuckians love their history, and his book is crammed with it. Crawfish Bottom: Recovering a Lost Kentucky Community is the story of a neighborhood wiped out by 20th century urban renewal—a story told through public records, and through a remarkable set of interviews.

What was extraordinary about the scene at Poor Richard’s Bookstore that day is that the city fathers of a half-century before had hoped to erase Crawfish Bottom—a poor, crimeriddled, flood-prone neighborhood along the Kentucky River—from the city’s memory as well as the city map. “When our kids grow up, they will never know ‘the Bottoms’ were here,” predicted Farnham Dugeon, a business leader and urban renewal advocate in 1965. As Boyd’s book—and the bookstore crowd—attest, that did not happen.

Boyd is director of the Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. He got interested in Crawfish Bottom 15 years ago, when he went to work for the Frankfort-based Kentucky Historical Society. In 1991 Jim Wallace, Boyd’s colleague at the historical society, had located and interviewed former residents of the neighborhood, collecting the stories of a displaced tight-knit community. Boyd’s book returns to those interviews and uses this collection of memories and folklore along with historical fact to build a picture of a place that is gone, but that refuses to die.

Boyd’s focus on oral history is the nexus of a couple themes in his life. A history major at Denison, his interest in music prompted him to take a class that gave him experience in a recording studio. It was there that he started to learn about digital recording—a technology that had academic applications when he was doing his graduate work in Folklore at Indiana University. Today he’s working on an open source online management database system that will allow anyone to search oral history archives. The framework for storing and accessing oral history will allow anyone, for example, to listen to fond recollections of Crawfish Bottom’s Mayo-Underwood School.

Boyd still gets excited about what he calls “the power of the story.” Oral history adds depth and richness to our understanding of the past, he says; it gives recorded fact a personal context. The Nunn Center’s collections—from interviews with Appalachian women about coal mining in the Great Depression to conversations with returning veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—help paint a more complete picture of the American experience. And while it may seem premature to label a 21st century soldier’s experiences as history, now is the time to record them.

“That’s the nature of oral history,” says Boyd. Whether it’s Crawfish Bottom or Kandahar, “if you don’t get it, it’s gone.”