“I tend to let go of the stories that most investigative reporters look at—fraud, political corruption, organized crime, Watergate-type stories—and stay with the corporate ones. Because that’s where the power is in this country. It’s not all negative. But if you’re going to illuminate power for your readers, that’s where you look.

It is 1980. The most famous investigative journalist you’ve never heard of is sitting in a café in Burma, drinking coffee. Mark Dowie ’62 is 41 years old and he has already lived a life that sounds mythic in the retell. He’s been a copper prospector in British Columbia, cowboy in Wyoming, and draft resister. He’s been a student of economics, a small businessman, and publisher of the provocative Mother Jones Magazine. A few years earlier, as a novice journalist, he had taken on formidable adversaries. His reports on the Dalkon Shield and Ford Pinto had exposed the chilling personal and corporate greed that led to horrible and unnecessary deaths. If his name was not a household word, his stories were.

Now the most famous investigative journalist you’ve never heard of is about to begin a journey that will answer one of life’s most compelling questions: Why am I here? But he doesn’t know that yet.

An old man with a bald head and angelic face approaches him in the café. Dressed in traditional Burmese clothing, the man is impeccably groomed. When he speaks, his English is perfect, bearing only a shadow of an accent. He introduces himself to Dowie. His name is Tuon San Dao, he says.

Later, Dowie would call Dao a traveling journalist’s dream. Although their encounter is purely chance, they immediately connect. Dao has traveled widely in the English-speaking world as a representative of the former Burmese government. Now he is what Dowie calls a “lower-case” democrat in a country that had been taken over by a ruthless military dictatorship. If the politics of the country had been different, he would have been a powerful man, says Dowie. But then their paths would never have crossed.

They spend the better part of two weeks together, talking philosophy and politics, telling their life stories. Dao steeps Dowie in the history of the country and apprises him of the current political landscape. He takes him to places only the Burmese know about. They set out together, traveling from Pagan on a riverboat down the Irrawaddy River toward Rangoon. When the weather gets bad, they get off the boat and take a train the rest of the way. Through it all, they talk and talk and talk.

When the time comes to part company, the gentleman that Dowie has come to see as a guru, guide, and friend asks if he can be his Burmese father. Everyone in the world should have a Burmese father, Dao tells him. His philosophy, he says, is that humans are the only productive species, that we’re all here to make something. Then he asks Dowie the question of a lifetime: Do you know what you’re here to make? When Dowie shakes his head, his Burmese father gives him the answer. You’re here to make trouble.

Dowie hadn’t set out to be the famous investigative journalist you’ve never heard of. In fact, he hadn’t set out to be a journalist at all. That was something he had stumbled into only a few years earlier. “I was completely unformed,” he said recently of his professional life up to that moment. He’ll admit that he’d always felt a need to challenge authority. Now Tuon San Dao’s pronouncement gave him a way to name what he had instinctively been doing. He came back home and settled into his work. He had found his métier, he says.

Of course, he’ll be the first to say that he’s had plenty of experience being in trouble. He was a placid baby, according to his mother. But he quickly evolved, he says, into what his parents called a “naughty boy.” At the age of nine, he, and later his younger brother, was sent off to boarding school, a rigid Anglican church school in the remote country north of their home in Toronto. (“They were kenneled,” their sister Anne likes to joke.) Two weeks before Dowie was to graduate, a headmaster read his diary, saw a mention of liquor, and expelled him immediately. Dowie had to write his final exams at a library in Toronto.

Although his father had him earmarked for an Ivy League education, Dowie was dead-set on going to a co-ed college. He secretly applied to Denison, and then lied to his father saying he had not been accepted at Yale, because he didn’t want to go into “a sea of preppies in blue button-down shirts, khaki pants, BassWeegen loafers, and camel hair coats.” At Denison he joined a fraternity, played lacrosse, and worked on the 1960 Kennedy campaign. “I was a little bit of a fish out of water,” he says, in a student body that he describes as so conservative he was redbaited by fellow students for campaigning for JFK.

John Schwabacher ’62 was Dowie’s best man when he married Patti Bugas ’61 in his senior year. Recently retired from Computer Rent, the Charlotte, North Carolina-based business he founded, Schwabacher describes Denison in the early ’60s. “We were the last generation that did what you were supposed to do—you go into the service. You respect the government,” he says. “Mark was the one among us who questioned things. Unlike a lot of people like that, he had a great thirst for the truth and the underdog. He was a little bit skeptical, and I don’t know where he learned that. There weren’t many people like that around us.”

Even then, Dowie’s persona was larger-than-life, his adventures legendary. There was the night he and his good friend Ham Schirmer ’62 streaked across campus at midnight and sat their naked selves down on the president’s steps—where they were “unfortunately noted,” as Schwabacher delicately puts it. Then there was the night he threw Patti’s engagement ring out the car window when she gave it back to him during a fight. Dowie organized what seemed like a hundred guys, recalls Schwabacher, to comb through the grass searching for it.

“He was absolutely looney-tunes,” agrees Charlie Glasser ’61, president emeritus of John F. Kennedy University. “He was a good athlete—and a good drinker, as I recall. And he insisted all the girls were in love with him.” Glasser laughs. “I could never understand it because I thought he was kind of ugly. I still do. But women think differently.”

Glasser remembers A. Blair Knapp, then-president of Denison, saying that the purpose of a liberal arts education was to create people capable of independent thought. “Now, I don’t know if Denison created anybody capable of independent thought. I think Mark arrived at Denison projecting independent thought, and maybe to some extent Denison helped that along,” Glasser adds. “At least it informed him about a lot of things. Mark challenges everything. He’s written some wonderful books that I think have irritated a bunch of people. But if you don’t stand up and shout about things, raise questions about things, nothing changes and nothing advances. And certainly Mark is an arbiter of advance in thinking.”

Back then, the young man who would become the most famous investigative journalist you’ve never heard of challenged the institution as much as he challenged the people around him. Twice he got kicked out of Denison, twice he talked his way back in. One time, he was arrested for transporting unlicensed liquor across state lines from West Virginia to Ohio—something he says he and his fraternity brothers did as a prank to have moonshine, a.k.a. cheap liquor, for fraternity parties. Intent on getting back to school for an early morning exam the next day, Dowie pleaded guilty. No one advised him that he was walking out the door with a felony.

“I was trouble at school,” says Dowie. “Can’t hide the record.” Pull your socks up or you’re out, he was told. And he did. In his last semester he earned a 4.0 and graduated on the dean’s list.

He’ll admit now to being an angry young man, a discontentment that found a voice through political opposition and activism. He was actively opposed to the war in Vietnam. (His arrest for failure to register for the draft set him up for a second felony.) In the years following, he became involved in the 1970s prison movement in California, which charged the criminal justice system with class and racial bias leading to a disproportionate incarceration of blacks and Latinos.

“I’ve mellowed,” he says. “I’m not as angry as I was as a young man. I don’t think anger as expressed by young people is particularly productive—the intellectual counterpart to Molotov cocktails. It just doesn’t accomplish much other than giving the media some photos and headlines.”

Still, Dowie’s career as an investigative reporter was born out of impatience. In 1976, when he was originally brought on board as general manager of the fledgling Mother Jones in San Francisco, it was because of his financial acumen—rather than what he knew about the copper industry or how he sat in the saddle. In fact, the idea of becoming a journalist wasn’t even a gleam in his eye. Part of his job involved sending out direct mail pieces promising serious corporate investigative work, which was the magazine’s purported mission. But he didn’t feel the editorial staff was making good on that promise. One day, in frustration, Dowie stormed in on a meeting for a showdown. “Where are these investigative stories we’ve been promising,” he demanded. “They started whining, ‘We don’t know where they are. We can’t find people who know how to do corporate work. We don’t have anyone to write them,’” he recalls. “It’s not rocket science,” he told them. “I’ll do it.”

He wasn’t just blowing off steam. Someone else might have enrolled in journalism school to learn how it’s done. The prospector-turned-cowboy-turned-businessman did what he had always done: put his shoulder to the wheel—along with every bit of his considerable intelligence, and a few summers during high school spent covering the sports and police beats for the Cleveland Press. Dowie went out, found an extraordinary story about what was happening to women who were using a widely distributed intrauterine device (IUD), and researched the heck out of it. In “A Case of Corporate Malpractice” (Mother Jones, November 1976), Dowie told the disturbing story behind the Dalkon Shield, recalled after 17 women died from the massive infection it caused. The device left countless others sterile. Dowie exposed the Johns Hopkins physician who co-invented the shield and stood to make a huge profit from it. In the rush to beat out possible competitors, the physician’s claim of the Dalkon Shield’s superior effectiveness was based on a statistically puny five months of data.

“It was a knock-out cover story,” says writer Adam Hochschild, one of the founding editors of Mother Jones. Until then, Hochschild admits, he had only seen Dowie as a nice guy who worked on all that business stuff that Hochschild, as editor, wasn’t interested in. “There’s always a certain amount of snobbery between editors and the business staff at any publication,” he says. “Getting good investigative material was hard. And, of course, the last place we would look would be to somebody on the business staff of the magazine who’s supposed to be dealing with budgets and advertising and that sort of thing.”

The story brought Dowie a lot of attention—professional and personal. “He has a magnificent presence. He’s extremely charismatic, authoritative but not domineering,” says Rachael Adler, who Dowie considers a daughter. (A friend of Dowie’s son, she was a teenager running from a troubled home when Dowie gave her, as she puts it, “a nest.”) “There was always substantial discussion at the dinner table,” she says, adding that Dowie would spend quiet moments doing things like teaching himself Chinese. “There were always interesting people around. It was the 1970s and there was a lot going on politically. I always felt like Mark was at the center—this happening person.”

Dowie continued on as general manager at Mother Jones, writing articles on the side. His second story would cost one of Detroit’s giant automakers millions upon millions of dollars and secure Dowie’s reputation as a hound dog with a nose for corporate scandal. (The story is still held up as a primer for aspiring journalists.)

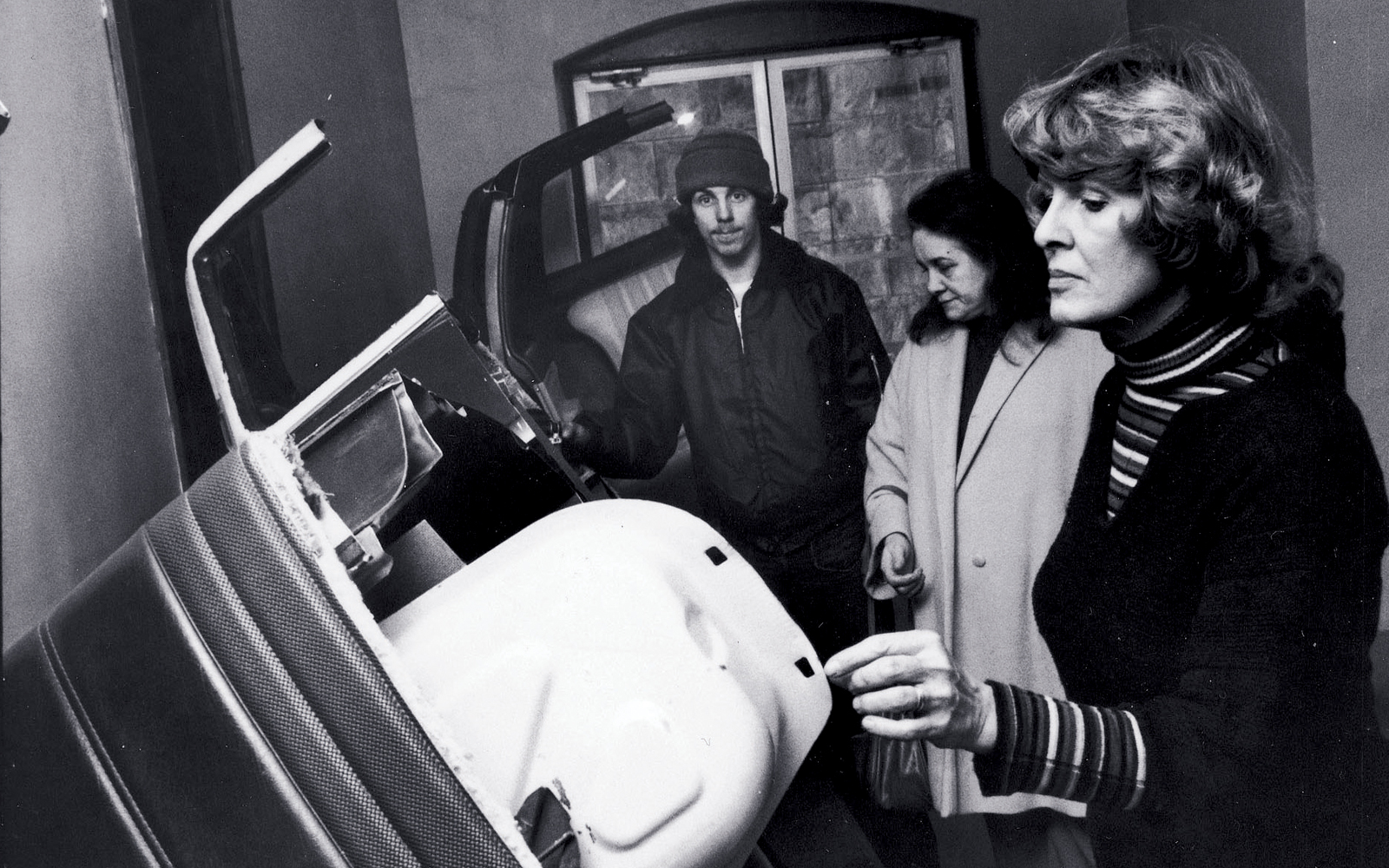

As Dowie tells it, he was having a drink after work one day with a friend, a “recon” man (short for reconstruction), who gathers forensic evidence at the sites of car accidents involved in lawsuits. His friend mentioned an unusual case where he had found neither driver responsible. Instead, the manufacturer was to blame. Dowie knew right away that it was his kind of story. “The whole goal of the tort system is to blame it on one driver or another. In the case of an auto accident, they always look to find operating human failure,” he says. “I could see corporate malfeasance all over this story. It turns out there was more there than I even thought.”

The accident involved the Ford’s celebrated Pinto, one of the best-selling economy cars at the time. What all the consumers who were flocking to Ford dealerships didn’t know was that the Pinto’s gas tank could rupture in collisions as slow as 16 mph—astonishingly, that’s according to Ford’s own crash tests. The company knew when it put the car out on the market that it could go from fender bender to fireball in seconds flat.

Dowie began looking at accident reports, fire commission records, court records. Knowing that Ford had lobbied hard against a proposed collision standard, he traveled to the Department of Transportation in Washington, D.C., to look at old files. “When people are fighting regulations, they use a strategy they call ‘paper inundation,’” he says. “They just flood the regulatory agency with paper, boxes and boxes, literally carloads of irrelevant paper—hoping that nobody is going to bother with them or that they’re going to have to take so much time to read through them that they’re going to get a big delay with the standard.”

Dowie likens his work to looking for a diamond in a dung heap. He spent the better part of a week in a stuffy file room opening one drawer after another and combing through those huge files. “In one of those boxes was a document that they wish had never left their own files,” says Dowie. It was his diamond—an internal cost-benefit analysis that weighed what Ford could expect to pay out in damages to the victims and families of those killed in explosive collisions against the cost of retrofitting the car with an $11.00 rubber bladder. It was cheaper, Ford had decided, to settle lawsuits than to change the design of the car.

“The story itself got a lot of media attention,” says Dowie. “Not me, but the story, because it was looking at things that business reporters had never looked at before, like cost-benefit analysis that placed a dollar value on human life and concepts that raised new paradigmatic questions about business, about criminal behavior, about insurance.” Despite the vehemence with which Ford denounced Dowie (rather than the allegation), 1.5 million Pintos were recalled. Dowie estimates the discovery of the memo cost Ford $55 million.

Dowie’s friends point out the coincidence that his former father-in-law had been a top executive at Ford who was already retired when Dowie wrote the Pinto exposé. (Dowie’s marriage to Patti Bugas broke up in the mid-60s.) But Dowie says that didn’t factor one way or the other into his taking on the story. “I would have done the same story if it was General Motors, I would have done the same story if it was Chrysler,” he says. “I might not have done it if it was Mercedes Benz or BMW because one of the things that appealed to me about the story was it was the Pinto, which was the people’s car. It was Ford’s attempt to compete with Volkswagen. It was the low end, under-$2000-under-2000-lb. car. The fact that people were driving their children to little league games in the car appealed to me.”

About a year after he wrote the Pinto story, Dowie was tipped off to another Ford story. “It was about a park-to-reverse problem that the company had where cars were slipping out of park into reverse,” he says. “But I turned that down, because then it would have looked like I was being vindictive. I gave it to another reporter.”

The way Dowie sees it, he’s a gadfly on the side of power. “I tend to let go of the stories that most investigative reporters look at—fraud, political corruption, organized crime, Watergate-type stories—and stay with the corporate ones,” he says. “Because that’s where the power is in this country. It’s not all negative. But if you’re going to illuminate power for your readers, that’s where you look.”

It’s ironic that it was a Pinto that Dowie rode to fame: In his heart of hearts, he’s a cowboy. He got his first taste of cowboy life during his college years when he would spend part of the summer with his fiancée, Patti, at her family’s ranch in Wyoming. After graduating from Denison, they went to British Columbia where he tried his hand at copper prospecting for a while. When he pulled out to move back to the ranch, he sold his shares for 32 cents. “I needed the money to pay for the trailer to get down to Wyoming,” he says. (Had he waited until a month or so later, when the value of the shares soared suddenly to $40, the rest of the story may well have been different.)

On the ranch, he had to prove himself to the other cowboys. “Anyone that is educated and is not a highly skilled cowboy and who reads books and listens to Beethoven at night as I did, they’d call a dude,” he says. “In the West, a dude is somebody from the non-ranching life who comes out there and rides a horse around and dresses up like a cowboy for a week or a month or a year. As the cowboy says, ‘All hat and no cattle.’”

But Dowie loved the work. He loved the hard physicality of it, he says, loved the outdoors, the grit, the sweat. “People make jokes about cowboys being like grunt labor,” he says. “But cowboys are very, very skilled workers. Go out and watch cowboys work and watch them rope and do the work they have to do to manage large animals and build fences and barns. And the best cowboys are also lay veterinarians.”

Dowie had always entertained the notion of following in the footsteps of his grandfather, who had been a veterinarian. “So here I was working with animals and taking care of sick animals,” he says. “And then when I got there full time, I went through the whole birthing process, which is very exciting. Calving is about two-months nonstop on any winter ranch where you’re trying to have them all in January and February. One calf after another is dropping, and you’re pulling calves, saving calves, doing everything. It’s very hard, and very exuberant work—which I still love. In terms of all the work I’ve done in my life, that’s the work I actually love the best.”

Years later, Dowie would discover Buddhism and make a connection between his cowboy life and his spiritual life. “Part of Buddhism is concentrating on mindfulness. And you have to be very mindful when working as a cowboy because it is dangerous work. You are working with very large animals, you’re working with large machinery and equipment,” he says. “It’s harder than sports. You have to be sober and very mindful of your work. I learned a lot about mindfulness by being a cowboy—without understanding what it really meant. Then when I started studying and practicing Buddhism I started to understand what I had learned as a cowboy.”

Even now, Dowie dons his hat and his chaps every spring to work the round-up—in exchange for a supply of grass-fed beef—athough, he says, it guarantees he’ll be walking funny for the following two weeks. (Most years he goes to the Montana ranch owned by his ex-wife and still-friend Patti and their son, Mark Harris.) “I think I’ve pretty much gotten to the stage now where I’ve got to give up some of it. It’s fun, but it’s pretty painful,” he says. “That said, I’ll go back out there next spring and probably jump on a horse and do it all over again. And double my dose of ibuprofen.”

Dowie has been married for 25 years now to landscape painter Wendy Schwartz. They live outside Point Reyes Station at the farthest end of long, thin Tomales Bay in Northern California. The peninsula on the other side of his place was once a 65,000-acre ranch, and his two acres were the humble cattle station with four cowboy bunkhouses. Dowie describes them as four boxes that he’s turned into a house, his office that doubles as a guest room, Schwartz’s studio, and a small cottage that Schwartz runs as a bed and breakfast. “The irony of it is that I left the bunk houses in Wyoming in 1964 and now I’ve ended up in a bunk house again,” he says. “It’s got a lot nicer material than the bunk house I left, but that’s been my life.”

Aside from his Asian sojourn in 1980, Dowie spent 11 years at Mother Jones. He eventually moved to the editorial side of the magazine, taking a turn as editor. When he returned from Burma, then-editor Deirdre English hired him as chief of investigative reporting. “With someone as talented as he is,” she says, “you just want to give him his head. Mark is the best of the best. He gets the story, gets the analysis, and he’s a good writer.” She remembers a standard scenario when she’d have to tell Dowie a story was too long. “He’d say, ‘Fine. I’ll just cut out the color,’” she says, “the scenes and characters and all the things that make something readable. We’d have that argument back and forth. He was so committed to getting the facts out.”

These days, Dowie is committed to getting the facts out about “conservation refugees”—indigenous tribes evicted from their traditional lands and left to live on the fringes of society, paradoxically, in the interest of conservation. In the last two years, he’s traveled to the Amazon basin, the Andes, Thailand, Laos, Burma, and the circumpolar region of Alaska to meet those who have been displaced or stand the danger of it. He calls the book an investigative history of the two sides: “This is unusual for me because it’s a good guy-good guy story—which I like. It’s harder and more challenging, but in a way more satisfying to write a nuanced story about two good guys that are at odds with each other than the clearer white hat-black hat mode of investigative reporting,” he says. “This story could have a happy ending.”

Dowie still rises at 5:30 to write. His goal every day is to produce 1,000 words. Some days that takes him until 10:30 in the morning. Other days, he’s still at it at 10:30 at night. “I love the chase,” he says. “I love doing the research and traveling and doing the investigation. I love talking about it on the radio [after it’s published]. But the middle stuff is like pulling teeth.”

In a career that’s 30 years and counting, that adds up to a lot of teeth pulling. He has more than 200 investigative pieces under his belt. He’s broken stories on the dumping of hazardous products in third world countries, investigated the American system of testing products and chemicals, covered the showdown between environmentalists and the northern California logging industry, and looked at the controversy of patenting chimeras. One of the five books that he’s published takes an early look into the darker side of transplant medicine. Another takes the environmental movement to task. (Losing Ground: American Environmentalism at the Close of The Twentieth Century was nominated for a 1995 Pulitzer Prize.) Two book shelves in his office are filled with anthologies, ranging from sociology, criminology, law, ethics, and fire science, that have reprinted his now-classic “Pinto Madness.” He’s received 18 major journalism awards, including four National Magazine awards. Yet in the first sentence of his professional bio, he describes himself simply as teaching science at the University of California Graduate School of Journalism. And therein lies a clue to why Mark Dowie is the most famous investigative journalist you’ve never heard of.

“He hasn’t sold out,” John Schwabacher says. “His score card doesn’t have anything to do with the things most people keep score with.”

“Mark didn’t seek the limelight,” says English. “He doesn’t like to put himself front and center. Had Mark gone to New York instead of Point Reyes he could have been more famous. But then he would have had to learn that lifestyle and become that person.”

Says Adam Hochschild: “It’s important to contrast his career with somebody like Bob Woodward, who made one of the great investigative coups of the century with the Watergate exposé, but then turned into a very, very different kind of writer whose books now are totally based on befriending people very high up in power and writing about them flatteringly. Mark went in a very different direction and really stayed true to his principals. He’s been able to make a living writing things that mattered. He’s one of my heroes.”

“The Pinto story helped my career,” Dowie admits. “It made me accidentally famous.” But on the subject of his renown, Dowie defers to an observation of Robin Williams: “Being a famous print journalist is like being the best-dressed woman on radio.” Such is the lot of a trouble-making Buddhist cowboy. Dowie was never able to find Tuon San Dao again in the years after his visit to Burma. But somewhere out there, you have to know, a Burmese father is smiling.

Sally Ann Flecker is a freelance writer and editorial consultant. She told us about Doug Donnelly’s battle for spiritual equity in the Summer 2005 issue of this magazine.