Mary Ann Bates ’06

has had an unlikely trajectory from her childhood starting in an Ohio Amish community to executive director of J-PAL North America, a regional office of the Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab at MIT, where she is one of the country’s leading champions of evidence-based public policy. We spoke to her about how evidence-driven decisions trump gut reactions and ideology, why she’s eternally optimistic, and her dream that someday, her unique work will become second nature for policymakers.

You lead J-PAL’s North American office. What is J-PAL North America trying to accomplish?

J-PAL is working to ensure that programs and policies to reduce poverty and improve lives are informed by science. We do that by bringing the scientific method and randomized controlled trials to the table to help decision makers. We work with state and local government, the private sector, and nonprofit organizations, as well as a network of affiliated professors at universities around the world.

A common theme through all of this is starting with a real humility about assuming we know what works and what doesn’t. We have a long history of cases where people were so sure something works, they think they don’t even have to test—then we find out the program didn’t work as intended. On the flip slide, there are a lot of hidden policy gems that influence people’s lives in ways no one anticipated. The work we do is a combination of the scientific method and detective work in trying to figure out what’s working—and why.

Can you give an example of an outcome that surprised you?

We evaluated the programs many cities run that offer subsidized jobs for young people during the summer. The idea is that these programs keep kids safe during the summer, while helping them learn skills that will increase their earnings in the future. Our affiliated researchers tested this in Chicago and New York City and found that the programs do help students get jobs during the summer, but they don’t seem to raise their ability to earn more money in the long run. But, as it turns out, the programs kept kids safe in the longer term, too—even after they were done with the program and back in school. Researchers found, for instance, that students who participated in the program were much less likely to be arrested for violent crimes, even after the end of the program. And in New York City, the data enabled them to see that young people were less likely to die after engaging in these summer jobs. If we hadn’t rigorously evaluated this program, and instead just assumed that the program helped kids get jobs during the summer and that’s it, we would have missed this important dimension.

And something people assumed would work but didn’t?

It used to be assumed that microfinance—where you give someone a loan and then they start a business and transform their lives—was a silver bullet. We know now from rigorous research studies that it’s not—work by J-PAL-affiliated researchers and many others show that microfinance can help some people, but it might not help others. There are many cases like this, where research can teach us something that cuts against conventional wisdom on what works. To me, this is why it’s so important to actually test things to see if they’re working, rather than relying on ideology and gut instincts.

In your TEDx Talk, you said that when we look to existing research to solve problems, too often we’re asking the wrong kinds of questions. What do you mean by that?

People often think that research is relevant only in the specific location where it was done. But in some cases, we see the same consistent, successful results replicated in wildly different places. Some of J-PAL’s strongest findings show that when you work with kids who have fallen years behind in school, targeting instruction at the child’s individual learning level (rather than their grade level, for example) can help them catch up. This kind of individualized tutoring was evaluated in many different contexts—from Kenya to India—and more recently in Chicago’s South Side. No one would suggest that urban Chicago is like rural India, and yet the underlying problem is very similar: many kids are learning years behind their grade level, yet teachers are incentivized to teach at grade level. When J-PAL--affiliated researchers evaluated this individualized tutoring program in Chicago, however, they found it led to huge learning gains, especially in math, which was incredibly encouraging. And it showed we can learn from research that’s done in very different contexts. That’s one of the most exciting studies we’ve worked on.

I was getting a lot of pats on the back about how I was making a difference in the world, but I had the distinct feeling that the things I was doing as a volunteer teacher were a drop in the bucket and may not have had the full impact I wished they had.

How do you determine which problems you’re going to address?

In some cases, we’ll start with an important policy question being debated and create an experiment that can help answer the question. Recently, an affiliated researcher looked at the impact of a doctor’s race and if that influences how people seek healthcare. They designed an experiment that tested the impact of having black men seek preventive care from physicians who are black and those who are not. The study found that when black men were randomly assigned to see a provider who was also black, their chance of getting a flu shot or being screened for cholesterol was dramatically higher. This kind of research can get at fundamental questions that inform conversations about diversity in the medical professions.

At J-PAL, we also create innovation initiatives that solicit research questions directly from government leaders and service providers who are working in the real world, and who want to know if programs are having the effects they hope for. We’ve looked at issues related to homelessness, healthcare delivery, educational technology, and the opioid epidemic. We also work with academic researchers and help match them with partner organizations who are interested in answering similar questions about which kinds of programs work, and why. This dual approach allows us to get at questions from both ends—harvesting from the thousands of projects out there and taking a strategic approach from a research perspective.

You penned an op-ed in Governing Magazine in favor of the bipartisan “Foundations for Evidence-Based Policy Act,” which was recently signed into law. The bill promotes the use of evidence and data for more efficient and effective government. What kind of impact do you think the bill will have?

When you run massive government programs, it can be really hard to see the counterfactual and to ask: “How will we know if this works? And can we determine in advance how we will evaluate whether this works?” I’m hopeful that this law will help people think about the need to plan for evaluation from the get-go.

The second really important dimension of the bill is creating more infrastructure and resources around the administrative data that we already collect, so that we can use that data more nimbly to figure out which programs are working, how, and for whom. We will be much better informed.

Describe your personal evolution as a Denison student to someone who is leading an entire paradigm shift in the way organizations use evidence-based research.

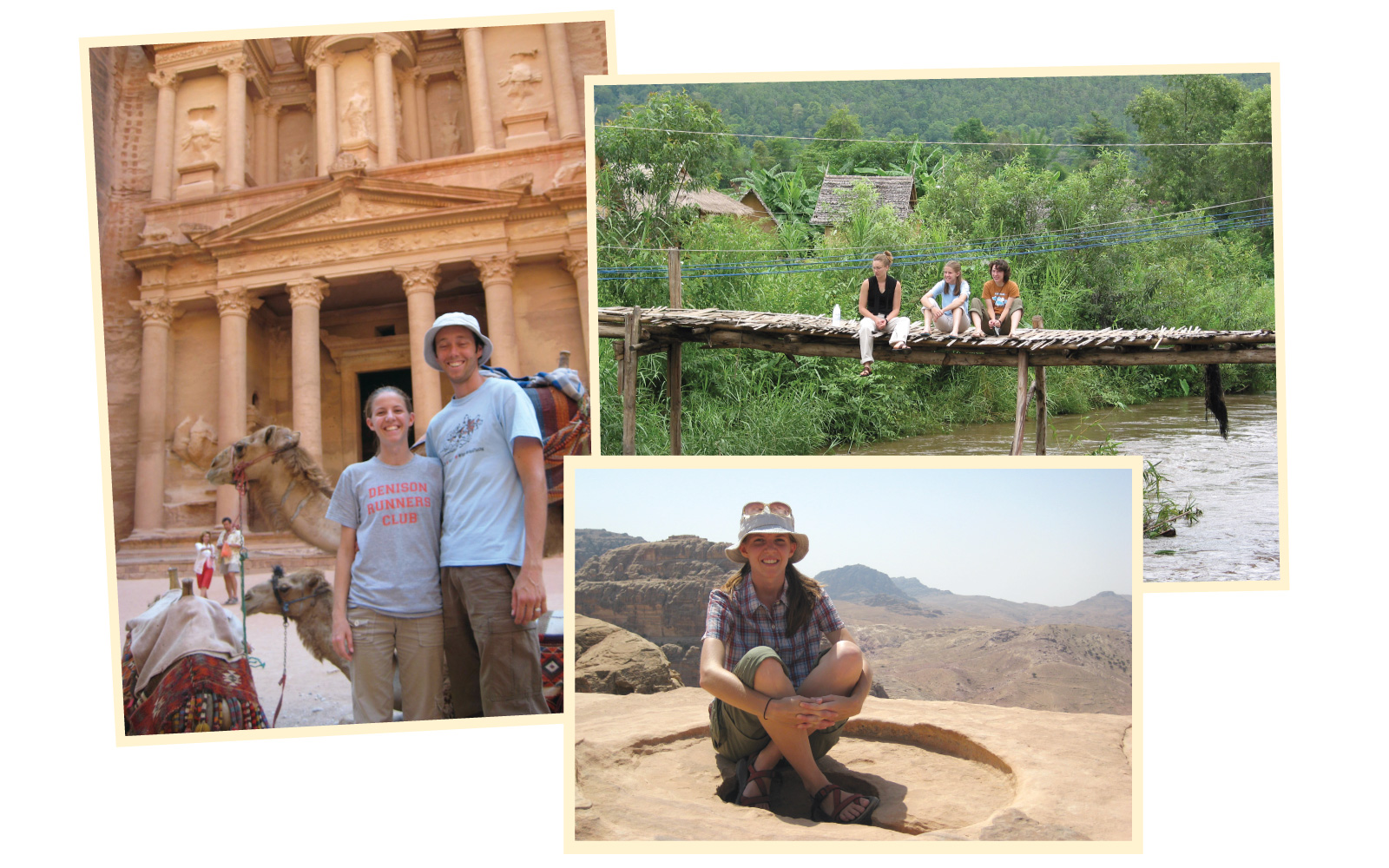

Even when I was at Denison, I cared a lot about addressing cases where people’s lives were limited by factors outside of their control. I taught in rural Thailand the summer after my first year, and then I had the opportunity to have two experiences right after Denison that shaped why I later chose to go into this line of work. First, I did a Fulbright in Switzerland after graduating, which opened my eyes to how incredibly satisfying research can be. And after that, I spent a year volunteering in Jordan as a teacher.

I was getting a lot of pats on the back about how I was making a difference in the world, but I had the distinct feeling that the things I was doing as a volunteer teacher were a drop in the bucket and may not have had the full impact I wished they had. I decided to study public policy in graduate school, because I wanted to be able to work at that level. While at UC Berkeley’s Goldman School of Public Policy, I got to know one of J-PAL’s affiliated researchers who did many of the experiments J-PAL is known for, and I was tremendously inspired by the work.

How did Denison help you launch into the person you are today?

Few things changed my trajectory more than Denison. My family is originally from Ohio’s Amish community where they limit education to eighth grade. Because my parents left the community, I could go to school. Until I arrived at Denison, I didn’t know the breadth of opportunities out there and the kinds of careers that could impact the world.

I’ll always be grateful, especially to the Gilpatrick Center staff who “found me” my first year and helped me think about what I can do in a whole new way. They introduced me to the Fulbright program and other postgraduate fellowships, and helped me think about not just what courses I could take the next semester, but how I wanted to think about my life’s work, profession, and career.

You still have a long career ahead of you. What do you hope you’ll one day be able to accomplish?

I would love to see the kind of work I’m doing right now no longer be considered unique or unusual, and to widely take hold in an institutional way. No website or online platform would roll something out without testing if it worked. Similarly, I would like it to become second nature for complex programs that are trying to solve homelessness, inequities, and poor health outcomes to evaluate their impact. I’m always an optimist—I will forever be an optimist—and I am very encouraged, because we see some of those seeds being planted now. I hope they grow and flourish and take root.