A little bit before 10 p.m. on July 13, 2013, Kelly Brown Douglas’s phone started buzzing with texts. The verdict in the case of the state of Florida vs. George Zimmerman—who was charged with second-degree murder in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin—was in. Douglas ’79, a religion professor at Baltimore’s Goucher College and an Episcopalian priest, turned on the TV and watched in stunned silence as Zimmerman was exonerated.

The next morning, Douglas headed to Sunday service at the Church of the Holy Comforter in Washington, D.C., where she was due to give a sermon. The mood was heavy and silent. Before the service began, parishioners in the predominantly Afro-Caribbean and African-American church were invited to share their feelings on the verdict. For more than 45 minutes, they spoke of their grief. Men and women were in tears, asking, “How could this happen?” Others were wondering aloud whether their children were safe. Doctors and lawyers told stories about being stopped by police for the crime of “driving while black.” College students talked about being roughed up by police. “They spoke until they had nothing else to say,” says Douglas. There were no answers that day. But Douglas couldn’t let it go. How had our country reached this point? And why did these things continue to happen? Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God (Orbis Books), her new book, came from Douglas’s wrestling with those questions. We talked with her about her research and how the country can begin to heal. —Dan Morrell

Why did the death of Trayvon Martin connect with you so personally?

There were two things that disturbed me deeply. One was just looking at him—he’s a young black kid. And doing nothing more than what teenagers do. I knew, of course, there were the other young black males and young black females who had been killed—innocently killed—because of who they were. But seeing his face, and perhaps connecting with my own son, I couldn’t let it go. Then, to see his mother and his father pleading for justice for this young man. And in the news, Trayvon was crucified. No one talked about the character of his killer. Everyone talked about the character of Trayvon.

So I could not believe, first of all, that the nation—other than the black community—wasn’t seeing the injustice in this. It was so obvious to me. All of these things were unbelievable to me, while they shouldn’t have been, because I’ve been black in America all my life. But they were. And I said, “I’ve got to say something about this.”

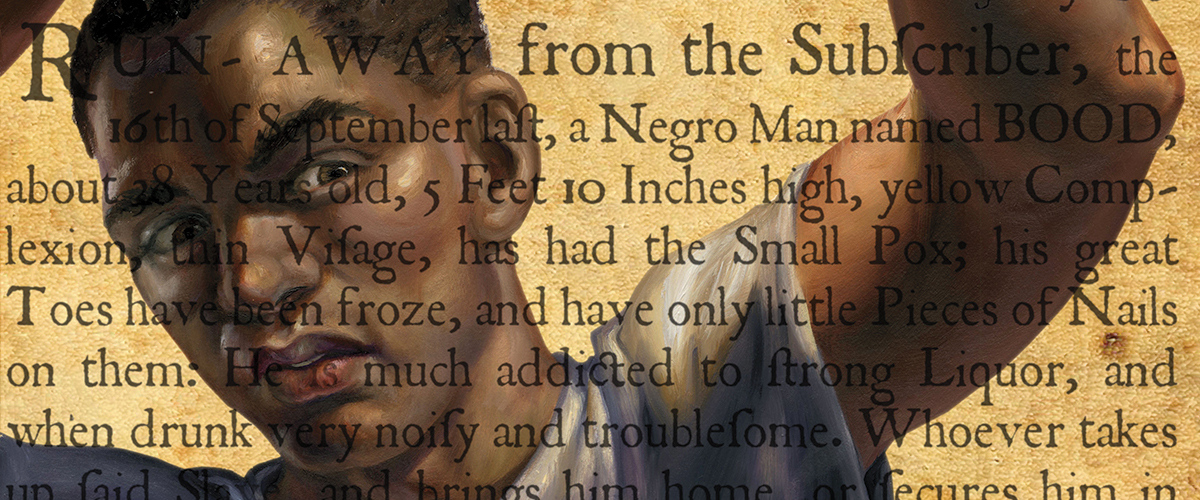

In the book, you provide a historical perspective on Martin’s death—arguing that the events of that night in Florida were set in motion before the Pilgrims even arrived in this country.

I think one of the things that we simply have to understand is the way in which America’s identity has always been a racialized identity, and the way in which America has come together to really protect whiteness in this country. And that our laws, our systems and structures, and our culture have been built to protect the culture of whiteness. We have not been honest about that.

And frankly, as I did the research, I didn’t know it would take me back this far. I was going to talk about how this nation has not dealt with the legacy of slavery. I felt that’s where I was going to begin. As I researched, I began to see that there was something behind that—this whole notion of the myth of Anglo-Saxon exceptionalism. I didn’t realize how deep that was in America’s collective consciousness.

And when something is a part of your base identity, that’s like going to a therapist. You know, you go to a therapist, and you try to figure out why you keep acting the same way you act, because you don’t want to act that way. You have to go back and understand what has led to that behavior. That’s what we haven’t done in this country. We haven’t seriously owned who we are and who we intended to be. And this nation intended to be an Anglo-Saxon nation. I’m not the first person that has said that. James Baldwin said it. Toni Morrison said it. Charles Mills said it in The Racial Contract.

And so, as I pushed back beyond slavery, it became so clear to me how embedded in our very soil this sort of white culture is, and how our very soil is racialized soil, and that the black body is just always on the outside of that.

Do you think that there was some awakening recently in large parts of the country—that people had been lulled into believing that we are in a postracial society?

I do believe that people were lulled into a sense of comfort. But I think that people have not been awakened from that until these recent protests in Ferguson, as well as in Baltimore, because I think that two things happened in those protests. One, there was a movement from below. And the black community and its allies changed the narrative and pushed back and said, “No, this isn’t going to go down like this.” And I think that it ignited this grassroots movement that emerged in the country.

In the wake of the murders at the Emanuel AME Church in South Carolina, you wrote an editorial for the Baltimore Sun in which you call racism a disease. And you say that treatment begins by naming it, calling it out, and dismantling it. It occurred to me as I was reading your book that this book seemed to be you doing that. This is you calling it out. This is you putting a name on it.

That’s exactly right. In part, the book was written to help us to see this thing runs deep. And so yes, no little fix here or there will do. We have to decide who we are in this country. I’m always reminded of W.E.B. Du Bois’ idea of the two warring souls. He talked about that in relationship to African-Americans in his book The Soul of Black Folks, his famous psychology of the African-American. He talked about a double consciousness and how we have these two warring souls—between being African and American. I think that speaks to the nation, in that our two warring souls are whether we are going to be a nation that lives in the legacy of the slave-ocracy and beyond, or whether we are going to truly be a democracy. And we haven’t decided that.

Let’s hypothetically say that the nation chooses to be that true democracy. What does the path to true democracy look like? And what is the role of the black church in that movement?

Just as President Obama alluded to in his eulogy for the Rev. Clementa Pinckney [murdered AME church member], we’re going to have to look at the way in which our structures and systems are discriminatory. When we talk about the fact that black and brown people disproportionately live in poverty, that black and brown children are disproportionately underserved in their educational systems, etc.—why is that?

That is systemic and structural racism. And we have to begin to look at the ways in which those systems and structures are indeed discriminatory. And to me, that’s violence. Systemic and structural injustice is violence. What we often look at is the violence that erupts on the streets. Well, that’s a response to the violent lives in which people have been forced to live. That’s what we have to begin to do—to look at the systemic and structural racism, period, which means dismantling some of these things, changing laws, changing policies, etc. So that’s one level. And then we talk about this sort of collective consciousness and what happens when, as President Obama put it, Johnny and Jamal go to apply for a job. And we know the likelihood is that Johnny is going to get it and not Jamal. We have to look at that.

In terms of the black church, it has always been in the forefront of racial justice issues. I think that it will continue its struggles and resistance and pushing back and naming the issues. And as we have seen in Baltimore, the church has been reignited in its call to provide sanctuary for black people. It will have to become even more energized in providing the services that are not provided in wider society, but also filling in educational gaps—as it has done—and providing food and shelter. But also to help people understand, and particularly our youth, that they have life options, and to begin to affirm them in ways that they aren’t affirmed in wider society. As my church did in the wake of the Trayvon and Renisha McBride killings, it will continue to talk to our kids about how to respond to police. And even when—as I tell my own son—even when you know you’ve done nothing wrong, that moment of humiliation could save your life. So we need to teach them how to move through life and stay safe, which the black church does.

The murders in South Carolina offer painful evidence of something that you’ve written about at length—about how black bodies have been sexualized and seen as a threat. Before the killings, Dylann Roof allegedly told the victims, “You rape our women, and you’re taking over our country, and you have to go.”

It’s all of the caricatures of the black body, all of the stereotypes of black people that have entered into the collective imagination of the country, so that when you see a black body, you see a threatening body. You see a black male body, you see a sexual predatory body. And to be sure, in the least, you see a dangerous, criminal, threatening body. There have been numerous studies that have indicated that people have almost visceral reactions, unwittingly, unconsciously, to the black body. Again, that’s because of the way—and I’ve talked about this—the black body has been introduced into this country as chattel, personal property. All of the stereotypes that have then been grafted upon the black body to convince people that the way things are is the way it’s supposed to be, that draws attention away from the real problem—the systems and the structures of oppression—and it places the blame on the people.

So one could say, “Yes, I believe black people should be free. But black people aren’t capable of being free.” What caricatures and stereotypes tend to do is mystify the real source of oppression. We have seen this play out in these recent incidents. Instead of looking at, let’s say, discriminatory policing, or instead of looking at discriminatory housing and employment opportunities, we now blame the victims. We say, “Well, you know, Freddie Gray was involved in drugs.” [Gray died while in Baltimore police custody in April.] Or we call people thugs like they did with Trayvon.

That’s what caricatures and stereotypes serve to do. And when it’s become so much a part of the soil, so to speak— when it becomes so much a part of the very marrow of this country—people believe them. And so you get a Dylann Roof. He feeds on this stuff. It’s not hard; it’s in the atmosphere. He believes it, clearly. I mean, we aren’t going to blame this on one crazy guy—obviously, he was disturbed. But it’s about more than one angry guy.

You teach religion at Goucher. What are the conversations like with your students in class?

Our students were very, very much engaged in all of these movements. They were engaged, obviously, because Goucher is in Baltimore. They were engaged in the Baltimore protests. They were engaged in the Black Lives Matter movement and the Hands Up, Don’t Shoot movement. They had staged their own die-ins and protests on campus, as well. The night of the uprising in Baltimore, a number of faculty and I were a part of that student group, as well as our college president. Spontaneously, we all convened in the student union. And there were a number of students. And we were there until midnight, watching the news, and having sort of a “listen in” and “speak out” discussion with our students. We were really trying to help them analyze what they saw in the news and also to understand what was going on.

Needless to say, these conversations spill over into the classroom space. And at that time, last semester, I was teaching black theology. So there were perfect, almost case-study conversations. I try to create an atmosphere in the classroom that is a safe space for discussing these issues. I try to help the students discuss them in a way that helps them begin to critically analyze what’s going on, as well as help them to talk about who they are and their own feelings, and to find their voice.

Sometimes, particularly this semester, for some students that meant difficult conversations. But hopefully we would lay the groundwork for those difficult conversations before it gets to that point. Not to engage in it would be to do a disservice to students anywhere.

You’ve written that progress, whatever that may be, will require these difficult conversations. Is your work as an educator another way that you push progress?

I think the educational institutions play a big role. We can’t educate our students the same way we’ve been educating them; we can’t act like these matters don’t exist. And so we have to help our students ask the hard questions. We have to help our students understand this matter of race in this country, and help them begin to take that on, and to figure out who they are in it, and what that means. We have to help our students reflect on what that means for the future, how to change that narrative, how to change the web of relationships in which they are involved. So these institutions of higher education—like Denison, like Goucher—they have to call the question for their students.

I also think that religious institutions have to take the lead in this and have a major role to play. We know, particularly with our white religious institutions, that there’s always been some ambivalence there. It’s not been a consistent response, as during the Civil Rights Movement and at other times. But I think that our religious institutions have to come to the forefront, because our religious institutions ought to be pointing to a different way of living and a different way of being, which means that they can’t follow the status quo. They have to call us. They have to point us to that “as if” future. And so religious institutions have to call the question.

At the beginning of the book, you note that the book was written for your son. What did you want him to know?

I always want him to know, as James Baldwin said in “A Letter to My Nephew,” that it’s not about you. I don’t want him to take in the hate of the world. I don’t want him to live in the beliefs about who he is that the world has projected onto him. I want him to know that he is special, and that it’s not about him.

At the same time I want him to know through my book, as I want others to know, that all is not lost. And that there are people advocating for a better way. That’s where I try to end the book, that there are people advocating for a better way.

I have no great expectation of the book at all. I just want to contribute, in the space of the world that I occupy, to the conversation, to try to move us forward.