I’m sitting on the stern deck of the Queen Mary, a once-majestic trans-Atlantic ocean liner. It is now forever moored in Long Beach, Calif., pinned in by a man-made reef, protected from the whims of the bay at the mouth of the Los Angeles River. Instead of smartly dressed travelers, it is swamped daily with hordes of tourists, both foreign and local. The ship is not what she used to be, of course, but out on the sunny deck with the seagulls hovering in the steady wind, if I close my eyes and concentrate, I can just feel her rock ever so slightly. But I must pay attention to the strange task at hand: learning to tie rope halters for horses at the annual meeting of the International Guild of Knot Tyers. I don’t ride horses, and my guess is that few of the six grown men, sitting in a circle with me on the deck of this ship, don’t either. No matter. All eyes are on our teacher, Mike Bromley. He’s about six-four and sturdy with dusty brown shoulder-length hair and a long beard, denim overalls, leathered hands. He’s the kind of guy who cries out for the moniker “Big Mike.” Yet he’s a gentle instructor with a disarmingly soft tone—more teddy bear than biker tough.

“That’s nice, real nice,” he gestures to a guy named Seth sitting on my right. “Now you have to make this next knot a Matthew Walker.”

On the other side of me is a knotter named Brad. He leans over me. “Seth, can you help me with this one? I have trouble with Matthew Walkers.”

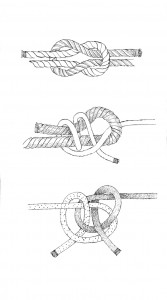

I’m wondering who this Matthew Walker fellow is and why he’s so troubling, so I ask Seth. “It’s an interlocked overhand knot,” he explains, as he nonchalantly corrects Brad’s work.

“Oh, okay,” I say. I’m a knotting novice and Cub Scout dropout, and I’m here to do research on my forthcoming book about the history of the noose. I’m also very impressed watching all these people expertly rig functional halters out of rope.

Besides me, 30-something and baby-faced Seth is the youngest guy here. By the looks of it, everyone else has at least 20 years on him. He’s wearing mostly black, despite the afternoon sun; a messenger bag with a biohazard logo rests on the deck next to him.

“I first learned Korean knot-tying,” Seth tells me, “so I don’t know many of the old nautical names for knots.” He keeps working on his halter, then suddenly pulls out his cellphone and shoots off a text to his girlfriend.

“Telling her where the bread crumbs are. She thinks they’re not there, but they are,” he says. “She’s stressed from organizing a 221B Con.” He sees the confused look on my face. “Sherlock Holmes conference.” As if I didn’t know that. Of course I knew that.

Brad complains some more about Matthew Walker, how he can’t tie it without looking. Most of the time, he says, he ties knots without looking at them. And then to impress me, he looks into my eyes while maneuvering a piece of cord with his hands. In about three seconds, he has executed a bowline knot.

Seth tells me that for him, knot-tying is meditative. Like many knot-tyers, who often come from the engineering set, Seth has a predilection for math, for problem solving—he studied physics and animation in college. So for him, intricate knot work is about confronting a conundrum with logic and symmetry—the process of resolution is relaxing.

“The more intricate the knot is, the more the stress comes out. It’s like a reverse massage.”

He picks up his phone with one hand and keeps working the line with the other.

The International Guild of Knot Tyers (IGKT) was formed in 1982, the result of a debate that began in the pages of The Times of London. A man named Dr. Edward Hunter claimed to have invented a new knot as a solution for broken shoelaces. He had been using the knot for many years and had named the knot after himself, calling it the Hunter’s Bend. But an English knot-tying evangelizer named Geoffrey Budworth didn’t buy it. He and a few other experts had seen that knot before. In fact, it was a knot originally called a Rigger’s Bend by American mountaineering expert Phil D. Smith, a description of it having been published in a book by Smith in 1953.

Budworth and his colleagues realized that perhaps Smith and Hunter had developed the knot around the same time; after all, the knot itself, with its “two interlocked overhand knots,” is considered a rather new technology in the knotting world. They realized that even though there were many books about knots, there was no organization that oversaw their naming and regulating. And so the IGKT was established in order to promote “practical, recreational and theoretical aspects of knotting [and] preserve traditional knotting techniques and promote the development of new techniques for new material and applications.” Today there are more than 1,000 members in 32 countries, with a heavy presence in the U.K. and the U.S.

In a world of cheap imports and new technologies, where most folks can tie only one or two knots—a world reliant on buttons and zippers, snaps and Velcro to secure and fasten and hold—the Guild is a sturdy bulwark determined to help those who can’t even tie their shoelaces properly.

There’s a bit of reflexive nostalgia among knotters, too, for a time when people could take string or rope and turn it into something useful. As one guild member named Glenn Dickey tells me, “You take this fiber that doesn’t have any structure and you give structure to it. You take something that is chaotic, a limp cord in a corner, and put it through an orderly sequence.Then it becomes something useful, something that has a form. That’s magical.”

Despite calling itself a guild, the IGKT is open to anyone who can write a check. This guild has no secret ceremonies or handshakes, and yet Glenn says there are some members, himself included, who will not share all their knot-tying secrets openly. Learning to tie knots well takes time and effort. He tells me, “I learned how to do it—if you get to my skill level, you will too.” He’s not kidding. “If you walked up to me and asked me if I could do a sheet bend, a square knot, a bowline, any one of these roughly 100 knots, I could do them without looking at a book,” he says. “Average people know about two or three knots.”

That makes me average at best.

But the IGKT is a guild in the very old sense of the word because, as conference organizer Lindsey Philpott explains, there is a “genuine long-term concern” for the craft. They are organized to maintain the skills that have for centuries been especially important to sailors. Indeed, knots were a readymade tool for managing rigging and sails, for docking and loading. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the beginning sailor could tie five or six knots. But as they became more experienced as sailors, they became better knot-tyers; many were known to decorate their belongings with the various knots they could tie. This was their résumé, so to speak, and it was a quick way for captains to know who had been around the block and who hadn’t. In the end, though, captains would decree which knots would be used on board—no one wanted to find himself perplexed about a knot when he was 40 yards up on the yards in what sailors affectionately called “the mangle zone.”

Before the dawn of the steam engine, though, Clifford Ashley, author of a book that is essentially the knotters’ bible, claims that sailors learned so many knots partly out of boredom because they couldn’t read to pass the time. When the “Sailors’ Aid” societies came into vogue in the 19th century, more sailors learned to read. It wasn’t “the advent of steam,” he believes, itwas reading that fostered the decline of the art of knot-tying. Though many guild members come to knotting through recreational sailing, at dinner Saturday night, I sat next to a guy who said he spent 20 years in the Navy, 30 years in the merchant marine, and studied to become a ninja along the way.

Mike Bromley has been a farrier and blacksmith for more than 40 years. Unlike many farriers, though, he makes his own horseshoes. It’s a point of pride for him, he says, but it’s also about safety. Mike grew up around big strong animals on ranches and knows what they’re capable of. That’s why he makes his own rope halters rather than purchase some manufactured halter.

“But do people still need to know how to tie rope halters?” I ask. “Well, they work better; they’re safer; they don’t break. I always say that the greatest tool you can have is a skill. Learn a skill, leave another tool at home. I can walk into a hardware store and buy 20 feet of rope and make a rope halter. But our culture in America is drifting away from that. We don’t produce anything anymore.”

This wasn’t the first time I’d heard guild members lament the decline of handy skills and doing it yourself in the modern world. I’m guessing there could be a bit of a libertarian ethos among some members, though no one talked to me about disaster “prepping” or privatizing the L.A. freeways (though there were many references to a decline in individual rights). But if knot-tying is a political gesture, it’s a counter to our consumer impulses—creating beautiful, useful things rather than buying them. In some ways, they are hipsters sans irony and have cornered the market on an obscure but very useful talent.

The president of the IGKT, Colin Byfleet, with his nautically appropriate surname, is concerned that the guild isn’t attracting enough young people.

Byfleet, a former chemistry professor, is a clean-shaven, energetic and athletic 70-year-old. He sports khaki pants, a dark gray Oxford shirt, brown loafers, reading glasses, and an upmarket English accent. “Many of our members will likely be dead in 10 years,” he declares, and he doesn’t want the guild to largely die off like the Shakers. They are attracting younger members (about 200 under 18), mostly through scouting. And through their web presence they are working to encourage knotters of all stripes to join. In general, he says, they’ve become more inclusive. One guild member claimed that the group used to be very exclusive and old-school, like you’d be hung from the yardarm if you used synthetic line.

“But we don’t need knots today, really,” I needle.

“Well, we don’t really … some people do. Climbers, fishermen …”

“Or maybe we don’t need to work with our hands in the ways that people did before us,” I say.

“Obviously there’s no logical reason to make something out of knots when a machine can do it in 20 seconds, or we can take advantage of incredibly low wages in Vietnam and have someone else do it for us. But when you buy something quilted or knotted from East Asia and it’s very cheap, that’s sad because it means that people don’t value the amount of effort that goes into making things. My wife quilts, and she reckons that one of her quilts took her a thousand hours. Well, what’s it worth? It’s worth nothing to anybody else.”

In the hands of an expert, a rope can be manipulated, pushed and pulled into place, sometimes leading to new forms or functions. Knots, of course, are for sailing, farming, and fishing, for surgery, rescue, and clothing repair, for climbing, caving, and camping. You’ll find knots on the stage and in the home. Knots have been used to count and keep track of information. They can be decorative, ornamental. They can be utilitarian, purposeful. Knots are used by butchers to tie up packages. Knots can be used to snare animals for food. Knots can also be used to kill human beings.

On July 13, 2011, Rebecca Zahau’s naked body was found hanging from a balcony at the Coronado, California, mansion in which she lived with her boyfriend, a CEO at Medicis Pharmaceutical. Zahau’s ankles and wrists (which were behind her back) were bound tightly with fairly sophisticated knots. Nearly two months after her death, the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department announced that she had committed suicide.

But that did little to silence the media. Her death was and is a sensation fueled by persistent rumors of foul play. Sheriff’s Department investigators have struggled to squelch these allegations by noting that no other DNA was found at the scene and by releasing a film of a woman tying her hands together behind her back.

Conference organizer Lindsay Philpott was approached by private investigators to offer his thoughts about Zahau’s apparent death by suicide. He’s one of the only forensic knot analysts in the United States and considered something of an expert among crime investigators (and a star among the knot-tying set). Philpott looks like a seaman—tall with a white beard and long white hair pulled back in a ponytail—and has the commanding presence of one, a deep voice with British inflection. Rumor has it that he also sings sea shanties every week at a pub in San Pedro.

Philpott is also a licensed engineer, and to him, Zahau’s case presented multiple problems of probability. Photos of the balcony railing from which she was hanged revealed no evidence of rope burns or bends in the railing—nothing to indicate that her 110-pound body had pulled on the railing as it went over the side.

“It was a pretty flimsy railing, and it wouldn’t have withstood that kind of an impact. As an engineer, I know what the dynamic force is of that body reaching the extent that it did and what it would have done to that railing. I also know what it would have done to the anchor, which was around the bedpost.

My question immediately was, well, how could she have known how long the line had to be so that she would fall to the right height? It was too incredible. The bed had not moved.”

But what surprised him the most was that she had gone through the process of tying her hands behind her back. To what purpose, he wondered.

Philpott was invited on HLN’s Dr. Drew show to talk about the case, and as Dr. Drew grows increasingly incredulous about the case, Philpott calmly replicates the half-hitches that Zahau would have tied in her suicidal state behind her back. He makes it look somewhat easy, but he’s tying his hands in front. And viewers have no idea that they’re watching a man who can tie more than 200 different knots without looking at a diagram.

Investigators of all stripes have been known to rely on knot experts to solve cases. Forensic expert Rodger Ide writes that knots often “provide very good interpretive evidence, helping to reconstruct how the crime or incident occurred.” Indeed, he says, “murders-by-hanging and strangulation are not normally preplanned in sufficient detail to mislead pathologists and forensic scientists.” Therefore investigators can learn a lot from the trace evidence found on the ropes, medical evidence from the damaged body, and information from the knots themselves. What was the ligature made of—rope, cloth, wire, chain? What kind of knot was tied and what can that tell the investigator about the knot-tying skills of the murderer or victim? Can those skills link them to any sort of trade or hobby?

In another case, a Florida drug-running couple was murdered and their bodies found, one wrapped in a carpet and the other in a blanket, tied with knots by someone who, Philpott says, had no idea what they were doing.

Based on Philpott’s assessment, investigators were able to rule out one suspect—a mountain-rescue expert, someone with knotting skills. “He wouldn’t have done anything like that. It would have been a matter of personal pride.”

He treats the death like a problem to be solved by examining all possible scenarios. Was there a struggle? Did it happen quickly or was it methodically planned? What type of line was used to tie the knots? Was it synthetic, cotton, Manila? Why would they choose that? Was it on hand beforehand? Or did they go out and buy special line? Or was it something that was lying around their house or in their car or boat? And from the knots themselves, Philpott says, he can tell the handedness of the person who tied the knots as well as his nervous state—if he was calm or manic. In a stressful situation, people will tie the knots they know. If they are trained, they will tie good knots. If not, like in the Florida case, they won’t.

“Do you know the story of Rasputin’s death? He was supposedly poisoned, beaten, shot, and then tied up and tossed into the Neva River. The story goes that when they found his body, they could tell that he wasn’t dead when they threw him in the river because he’d gotten one arm loose.”

Learning to get the knots right seems to be the first law with knots and knot-work. Otherwise, the knot won’t function or the knot-work will look awful. Glenn Dickey is teaching a class on how to make mini-bell ropes. I decide to put this law to the test and see whether or not I can get it right or if I can create something, anything, even if it’s not completely, you know, correct.

A few men grab chairs and sit close to Glenn at the back of the capstan room. He begins by telling the group to follow him closely and not be experimental.

“You can do that later,” he chides.

The first step of the process is to braid six strands of rope. I lean to the guy sitting next to me and whisper, “I can’t even braid my daughter’s hair.” He laughs. “No seriously, I really can’t.”

Glenn has mercy on me and begins the process for me. But after the first few steps, I want to get up and jump off the ship. I have no patience for this. Everyone else is intent on learning how to do this, and they patiently wait for Glenn to help them make the next move—and I’m as fidgety as my 4-year-old.

One guy messes up, and Glenn tells him, “Don’t worry. The second language of all knotters is profanity.” Then he squints at the work of the knotter sitting behind him. Glenn says, “No, that’s a straight crown. You need to do a modified crown.”

All the while, people come in and out, look around curiously and turn around. A man in khaki shorts and a neon green tank top walks into the room and exclaims, “Oh, knot-tyers!” (as if he knew) and then walks back onto the deck of the ship. And then an attractive blond woman walks by our little group. Without looking up or skipping a beat:

Knotter 1: “That looks like ‘so-and-so’s’ very attractive wife.”

Knotter 2: “Really? I don’t know how she puts up with him.”

Knotter 1: “Faded contact lenses.”

At least two hours go by, and we’re still tying—or the others are. I’m just waiting for Glenn to help me with the next step. And, I’m getting hungry. Glenn looks at me, a disaster of a mini-bell rope in my hand. “Are you feeling bewildered, overwhelmed?”

“Yeah, Glenn, a little.”

I glance out a porthole to the water beyond and watch a few gulls hover and dip. I’m not sure if the sailing life is for me. As if on cue, one of the gulls cackles. A family of tourists wanders into the room. With them is a little girl in a yellow sundress about my daughter’s age, who squats down to tie her shoe. She works the laces over and under. Struggles. And then, success. It’s almost magical.

Jack Shuler holds the John and Christine Warner Chair at Denison and is an associate professor of English. His third book, The Thirteenth Turn: A History of the Noose, will be published by PublicAffairs Books in August.