Alzheimer’s disease is generally acknowledged as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States, though its position is likely underestimated due to its collateral damages.

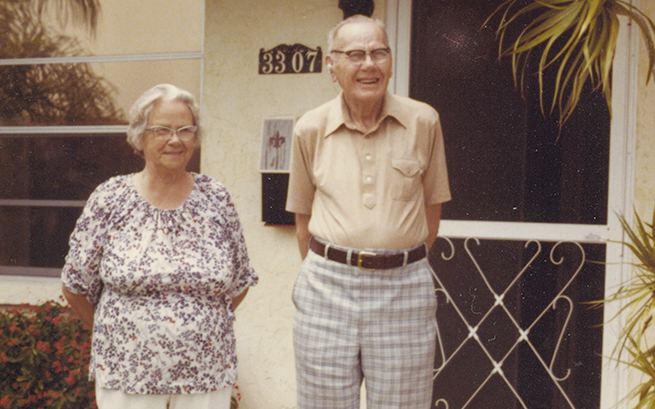

For some years, Andy Carr ‘57 says, things with his parents seemed normal. The couple had retired to Florida after long careers—he as a research chemist with DuPont and later with Imperial Chemical Industries, and she, with a master’s in education, as a teacher of handicapped children. Even when he visited from his home in California, he didn’t really observe anything out of the ordinary.

“Alzheimer’s disease is generally acknowledged as the sixth leading cause of death in the United States”

But at some point, Carr began noticing odd moments in his phone conversations with his mother, “things that didn’t make sense.” Small slip-ups. “She would call me and I would say ‘How’re you doing?’ and she would say ‘Fine—how’re things in Cutler?’ Now, Cutler is the town in southern Ohio where she was born and raised, and I had not been there at all in many, many years,” he said. “I would say, ‘well, I’m in California,’ and she would say, ‘Oh, of course you’re in California.’”

Carr retired 16 years ago at age 62 after a successful career as a neurologist. He served in Vietnam—one of two physicians in his specialty there, he says—and published a book about the experience, titled The 8th Field Hospital. When he returned, he practiced in a California hospital system, eventually becoming coordinating chief of eight facilities and an associate professor of neurology at UC-Irvine. He saw a lot of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s patients in his practice.

Still, it took some exceptional behavior for him to surmise that the changes in his mother’s behavior went beyond ordinary age-related memory loss and might be something more serious, like Alzheimer’s disease. Most unsettling were the 911 calls she began making. Once, when the police came and asked her what was the matter, she told them that she was scared because there was a woman in her bathroom that she didn’t know. When the police checked, they found it was Carr’s father. The police contacted Carr, who asked his mother why she thought her husband was a woman.

“She said, ‘Oh, you know how he looks like a woman sometimes?’” But he didn’t. Not long afterward, Carr’s father, who also was declining, went into a nursing home. At that point, his mother’s deterioration could no longer be hidden.

For groceries, she gave some neighbors a full book of checks, all signed, and told them to use them whenever they needed to shop for her. For two years, unbeknownst to Carr, a nearby relative had been handling the bills. Friends at the bank balanced her checkbook for her, though when Carr came to visit, and wanted to review her accounts, she could not help him find the bank. A giant pile of unopened mail on the dining room table made him realize that his plan to put his mother into assisted living in Florida was too late. It was time, Carr decided, to move his parents closer to him and his wife in California.

Despite the scale of the problem, and what might be deemed only modest progress in the field, somehow Jim Summers ’77 projects an air of calm when he talks about the search for Alzheimer’s treatments.

It often causes individuals to succumb to illnesses like pneumonia, or to stop eating and drinking, and those things will kill you. If you live to be 95, as it seems more and more people will, you have a 50 percent chance of developing Alzheimer’s.

In the United States alone, the proliferation of the disease has a daunting quality. Approximately 5.2 million people were afflicted in 2013, at an estimated cost to the nation of $203 billion. Experts expect that figure to rise to $1.2 trillion by 2050.

The global picture is even more grim, and it comes with sad ironies. As less developed nations slowly realize basic quality-of-life improvements, longevity in those areas will increase. And with longevity comes increased incidence of Alzheimer’s. Around 30 million have it worldwide today, according to the Alzheimer’s Association; by 2050, the number is expected to spike to 100 million. During that time frame, on the continent of Africa, incidence will rise 480 percent, a growth rate that puts it only in third place, behind Asia at 500 percent, and South America at 530 percent. The looming tide of Alzheimer’s and other dementias is rightly considered an epidemic of unprecedented scale.

Alzheimer’s can be definitively diagnosed only after the death of its victim. As is now widely known, its ravages appear as widespread plaques and tangles in the brain. And while the massive battles against cancer and HIV, for instance, have resulted in progress in treatment and prevention, there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease. No one would say with any conviction that there is even such a thing in sight.

“I am absolutely optimistic—and I think you have to be to work in this business,” Summers says. “If you look back over the past few years, the past couple of decades even, the amount of knowledge being accumulated about Alzheimer’s disease—its underlying causes and how to diagnose it more effectively—will give us a lot of opportunities for some significant breakthroughs.”

Summers is vice president of neuroscience discovery research at AbbVie, a Chicago-area biopharmaceutical company that was spun off from Abbott Laboratories at the beginning of 2013. Projects he oversees comprise one of the largest Alzheimer’s drug research efforts currently under way. After Denison, Summers earned a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Harvard, and went directly to work for Abbott. At a dedication symposium for the new Ebaugh Laboratories on the Denison campus about two years ago, he laid out some of the challenges facing researchers.

The fight against Alzheimer’s, Summers explains, takes place on two main fronts—treatments that might slow or even prevent the disease, and treatments that address symptoms. AbbVie pursues research on both, though it is widely acknowledged that a “cure” for Alzheimer’s, what Summers calls a “disease-modifying” treatment, remains some distance away.

Which is not to say that there has been much relief produced on the symptomatic side, either. The Alzheimer’s Association is the predominant forum for information on the disease. On its website, alz.org, some text under the “treatments” heading grimly sums up the state of medicinal relief today: “Although current medications cannot cure Alzheimer’s or stop it from progressing, they may help lessen symptoms, such as memory loss and confusion, for a limited time.”

The phenomenon of simultaneously having an affliction and not being able to comprehend that state is known as anosognosia, and it can be among the more frustrating aspects of caring for dementia patients.

The invisible transformation from noting moderate mental difficulty to having no awareness of one’s condition can take place with breathtaking speed. Andy Carr, now retired from medical practice for some years, is quite cautious about discussing medical matters. But he does remember anosognosia.

“The only clinical pearl I can give you is that when a person came to my office and said, ‘You know, my memory’s going on me; I have problems thinking about things; I think I have Alzheimer’s,’ then chances were that he didn’t have it,” Carr says. “But when someone brought his Uncle George in, and said, ‘You know, he’s not playing with a full deck anymore. He seems lost,’ but Uncle George says, ‘There’s nothing wrong with me,’ chances are that he did have Alzheimer’s.”

Neuropsychologist Rachel Andaloro ’06 sees a fair bit of anosognosia, and although she is as dispassionate as any researcher can be, she admits that it can be an unsettling phenomenon. In addition to her work in private practice, Andaloro also contributes to large-scale clinical trials sponsored by pharmaceutical companies such as Merck, administering neuropsychological assessments to determine whether individuals are appropriate candidates for the studies. After Denison, she received a Psy.D. in clinical psychology from Indiana University of Pennsylvania, completed her internship in clinical neuropsychology in the psychiatry department at Harvard Medical School, and then remained there for a two-year postdoctoral fellowship in neuropsychology.

The tests that Andaloro conducts measure various aspects of memory and language or “word finding”—how many items of a certain category can you name in one minute? How many words that start with a certain letter? Subjects also are asked to identify a series of objects shown in pictures, beginning with basic items such as a cup or a dog and progressing toward more complex identifications like “xylophone.” Various dementias present a variety of symptoms, but poor performance in both memory storage and wordfinding capacity is a telltale sign of Alzheimer’s.

“I have tested Harvard graduates, MIT graduates—very intelligent, verbally fluent people—so when they experience difficulty in getting words out, difficulty in communicating and expressing themselves, they find it very frustrating,” Andaloro says.

Some of her subjects, like those Carr saw during his career, are brought in by concerned family members. Others have a significant family history and want to receive an assessment or a baseline measurement. “A lot of times,” Andaloro says, “our testing will essentially magnify the problems they are having, so it’s hard for them. They know they are struggling, but can still rely on cues from their household or neighborhood if they are not doing anything out of the ordinary. Our testing can be novel to them, and to the extent that it magnifies their deficits, it is sometimes one of the first times it solidifies for them that this is a possibility. Sometimes it is evident—you can see it in their eyes—and you sort of get this sinking feeling in your gut.”

Neither of Andy Carr’s parents seem to have had time for self-awareness about what was happening to them as Alzheimer’s set in, and in many respects, as Carr puts it, their final years of life were “a long haul.”

With difficulty, Carr was able to convince his diminished mother to return with him to California. They took his father, too, on the same trip. Not surprisingly, the trip itself was unpleasant. At the airport, Carr’s mother was certain they had arrived at a train station. On the plane, while his father had a catheter and did not have to leave his seat, his mother was agitated and frail, and Carr’s wife had to help her into the restroom multiple times. And as with many dementia patients, the unfamiliarity of the experience took its toll.

“It seemed like the flight changed everything,” Carr says. “By the time she got to California, without her circumstances and her familiar surroundings, she had just deteriorated.”

His father’s health, too, began failing more rapidly, and while most Alzheimer’s patients do not enter hospice care, Carr’s work in the hospitals allowed for some accommodation. He visited whenever he could. “I went up to see him, and he said, ‘Who are you?’ And I said, ‘I am Andy, your son.’ And he said, ‘Who?’ I said, ‘Andy.’ And he said, ‘I don’t hear very well.’ So I showed him my nametag. And then he said, ‘Well, I don’t see very well, either.’ And that was the last meaningful thing he ever said to me. Not meaningful, exactly—but he answered the question, so to speak.”

The most difficult part of Carr’s mother’s disease, for him and presumably for her, was her passage through one of its most common and distressing stages—paranoia and attendant agitation. “One time she said, ‘I can’t see very well. I can’t read. I think my eyes are going. I need to see the eye doctor.’ So I took her to see the eye doctor, and he said that her vision was fine,” Carr says. “She couldn’t read because she couldn’t understand what she was seeing. Two days later she told me she needed to see an eye doctor. I told her that I had taken her to one, and that he had said she was fine. She said, ‘No, you didn’t. You’re just being mean to me. Take me to the eye doctor.’” That interaction, and others like it, were repeated in a host of variations. During another conversation about the eye doctor, she physically hit him in frustration. He couldn’t believe it. She had been extraordinarily gentle all her life and had never even spanked him.

Also like most Alzheimer’s suffers, her memory began to disappear backwards. When she first arrived in California, for a time she spoke about people and places she had known in Florida. After six months, she forgot about Florida and would talk about occurrences in Massachusetts where Carr grew up, and finally she could remember only things that occurred in Ohio where she grew up and married.

When his stepdaughter was to be crowned homecoming queen, Carr took his mother to the game. She enjoyed the pageantry, but kept asking him why he wasn’t down on the field, playing in the high school band, where he belonged. And finally she could not recognize him. “She’d say, ‘No, my son is much more handsome than you are,’” Carr says. “Because she remembered me from when I was a lot younger.”

“What we call it is forgetting on a temporal gradient,” Andaloro says. “First it will be what they did yesterday, what they had for dinner or lunch, and then they will kind of go back in time. In moderate to advanced stages, they will forget the names of their nieces and nephews, or their grandchildren, and then their children’s names. They might still remember their brothers and sisters but then that will go. It shows how deeply ingrained some of those older memories are. The remote memory is really difficult to uproot. But eventually the pathological process progresses to destroy those memories, too.”

“Enemies of the Brain”

Enemies of the Brain

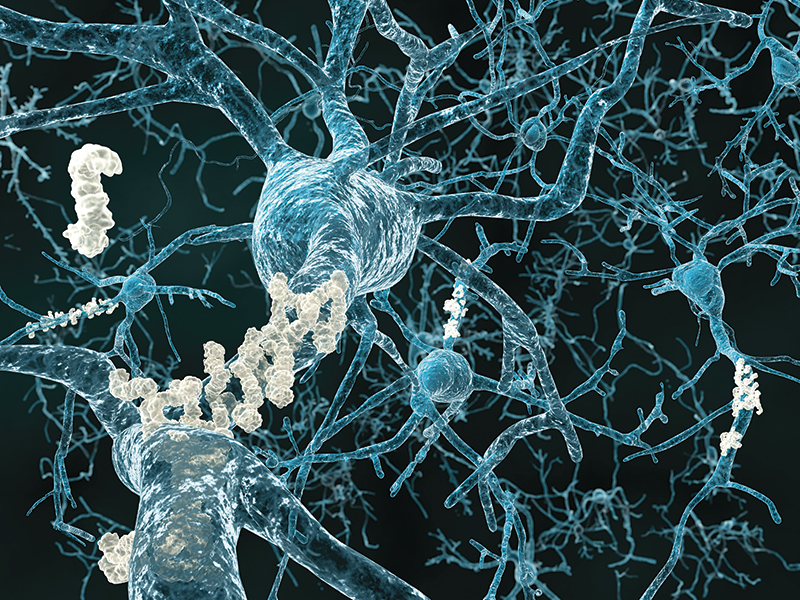

Alzheimer’s disease is now so widespread and so widely discussed that the phrase “plaques and tangles” becomes more familiar every day. These refer to the ways in which the disease physically attacks the brain. Visible under a microscope, presence of plaques and tangles indicates a definitive diagnosis, which can be made only after death. And while science understands a great deal about their composition and how they act to destroy the brain’s functions, the two phenomena are still the same two signs that were observed in 1906 by Alois Alzheimer, a German psychiatrist and pathologist, when he looked at the brain of a former patient—a woman who had been afflicted with memory loss and hallucinations before she died at 55. In this major respect, our understanding of one of the most basic aspects of the disease has not changed much for more than a century.

Both plaques and tangles seem not only to inhibit the brain’s functioning, but also to physically damage it. In photographs, brains ravaged by the disease look like they have been badly eroded by storms.

Plaques

Alzheimer observed a build-up of a substance on the brain’s cells, around which the brain had atrophied. That substance is now known to comprise mainly the protein amyloid-?.

One pharmacological approach to this problem that has proven unsuccessful has been to try to inhibit the various steps that lead to the creation of the amyloid proteins in the first place. While the assembly line making the plaque’s building blocks could be slowed, the approach has not improved the cognitive functioning of patients.

Various pharmaceutical companies have been involved in the development of bapineuzemab, which attacks the protein itself, but in 2012 it was shown to have limited effect.

Another approach, notably with the drug solanezumab, has been to attempt to break up the protein where it has deposited in the brain, releasing it into the bloodstream where the body may process it. In late 2012, the drug manufacturer Eli Lilly released modestly encouraging results from major clinical trials using this method.

Tangles

The other main visible hallmark of Alzheimer’s is the presence of fibrous tangles, composed of the tau protein, within neurons. Researchers focused on this enemy, sometimes called “tauists,” believe that the excessive presence of the protein disrupts brain function.

In Alzheimer’s patients, tau is a good protein gone bad. Normally tau supports the microtubules that neurons use to communicate with each other. But in Alzheimer’s disease, tau can become “hyperphosphorylated,” and its sturdy qualities become a detriment. It stops supporting neuron communication and begins to aggregate, ultimately disrupting normal functioning of the cells where it collects.

Scientists have worked to prevent the transformation of good tau protein to bad, but results of this effort have been inconclusive.

This past summer, AbbVie presented results from the latest round of clinical testing for its ABT- 126 molecule, a drug that then was roughly at the midpoint of the overall testing process. While to the outside observer the performance of the drug seemed positive, no one calls the Nobel Committee with such results. Many drugs make it as far as ABT-126 did, but never advance much closer to the marketplace. In fact, less than a year after the release of those results, AbbVie suspended ABT-126 research as it relates to Alzheimer’s. While the next series of clinical trials also showed positive results, they weren’t quite promising enough, leading researchers to shift the focus of ABT-126 from Alzheimer’s to cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia. Disappointing for Alzheimer’s patients, perhaps, but the process goes to show how frustrating it can be to research drugs aimed at this particular disease. And though AbbVie won’t continue with that line of research for Alzheimer’s specifically, the process nonetheless taught them something.

“There are only two approved classes of drugs for Alzheimer’s today and both of them offer, I think, a fairly modest benefit,” Summers says. “What we saw in these trials was consistent with that kind of gain at best. It isn’t something where you would go out and say these people can now perform third-level calculus where they weren’t able to before.”

Summers is referring here in part to the drug donepezil, a product from Eisai Inc. and Pfizer Inc., marketed under the name Aricept. On the most basic memory and cognition tests used to measure Alzheimer’s patients, most notably the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale, or ADAS-COG, treatment with donepezil results in improvement in just a few weeks.

But the damage in the brain cannot be reversed. What donepezil is actually achieving—what any palliative drug used to fight Alzheimer’s achieves today—is a brief respite, a slight improvement during an inexorable decline. It is relief, to be sure, but it is heartbreaking, too, in its temporary nature.

ABT-126 and donepezil both worked, but in different ways, on a similar aspect of the disease. “One of the things that happens in the course of Alzheimer’s is that the neurons in the brain that communicate with each other, using a chemical called acetylcholine (ACh), begin to function poorly and eventually die. Alzheimer’s brains have a deficit in ACh communication,” Summers says. “What donepezil does is try to prevent the degradation of ACh. It keeps it around longer and therefore makes more of what you have left. What ABT-126 does is to act as if it were ACh. It is a surrogate for ACh, so it works through the same receptors on neurons that ACh works through.” The initial results of the ABT-126 clinical trials— measured against placebo and donepezil—suggested a couple of things, at least. First, given the fact that as Alzheimer’s progresses, the body uses up its ACh supply, so supplementation with a surrogate sounds promising, especially if the dosage could be effectively increased. Second, some kind ofcombination of the two approaches—protection and replacement— may be efficacious. “Further clinical studies showed that these concepts were correct,” says Summers, “but the improvement was small.”

Though the research has taken place in 43 locations around the globe, those ABT-126 results were just one small piece of an enormous research effort—what an expert at Cornell referred to a few years ago as the “Wild West” nature of the field, where “there are no targets not to shoot at.” Relief for a large number of sufferers is some time away. Still, keeping patients out of a nursing home for six months, or a year, or two years, especially given their often advanced age, could be a great boon. The economic benefits of delaying 24-hour expert care across an enormous afflicted population cannot be overstated. And the personal relief is not insignificant.

“We’re trying to give them a little bit of help so that they can remember better,” Summers says. “So that they will know their children and their caregivers. So they will be able to think through some fundamental tasks like what they want to wear tomorrow, what they need to do to fix dinner tonight—and to be able to do that longer than they would otherwise have been able to do.”

He is joking when he says it, but Andy Carr is quick to tell you that he is “doomed.” Indeed, there is significant evidence of a genetic component in Alzheimer’s—most notably in early onset of the disease—and several massive studies are under way exploring this facet.

Carr says he doesn’t worry about it. Meantime, he keeps the kind of schedule a doctor would likely prescribe for him. He fishes in Alaska once a year, and more often than that in Mexico. Twice a week, he plays poker with a large, rotating social group near his home in Novato, Calif. He does all the cooking for himself and his wife, and maintains a large garden. He walks three miles a day, without fail.

While he doesn’t hear very well, he is an avid birder, and the birding gang he runs with has a number of sharp-eared members, so they make a good team. On the day that I first spoke with him by phone, he had been out all morning and had logged a handful of black oystercatchers. Not long ago, he spotted a blue-footed booby, extremely rare in California, the northernmost part of the bird’s range.

When his father finally died, Carr gave his mother the news. The couple had been extremely close, married 60 years. Inseparable—even insular. But in what Carr describes as a kind of blessing, his mother’s mind had retreated so far back that she no longer had a need, or impulse, to mourn. “When I told her, she said, ‘No, no—I knew that. He died a long time ago,’” Carr said. “There was no emotion whatsoever. No discernible change. When I asked her how long he had been dead, she said, ‘Oh, a long time.’ I think she had just forgotten.”

David Zivan ’88 is editor-in-chief of Modern Luxury’s CS magazine and group editor of the company’s six other Chicago titles. Zivan is also the former editor-in-chief at Indianapolis Monthly and was an editor at Chicago magazine.