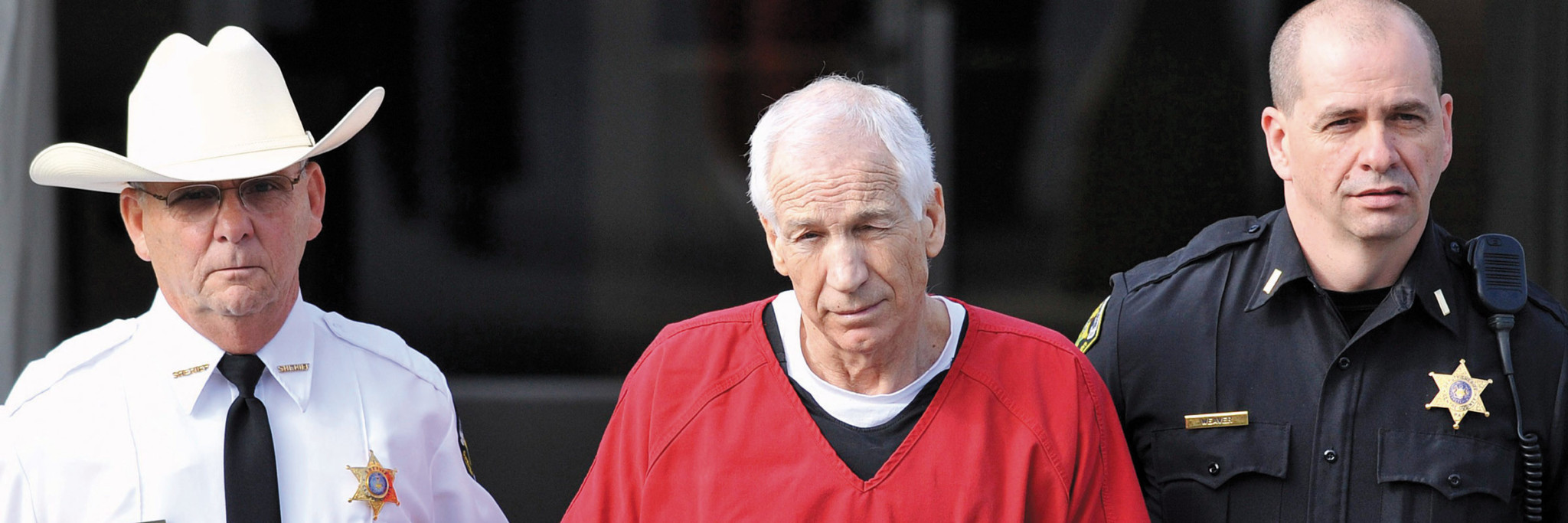

Jerry Sandusky faced 48 counts of child sex abuse involving 10 boys over a period of 15 years. The trial brought the national media spotlight to the small town of Bellefonte, Pa., just a few miles from Penn State University and the stadium …

Long before John Cleland took the bench for the highest-profile criminal case of his career, there were hints of the circus to come.

This was late 2011, shortly after Cleland—a senior judge in the Pennsylvania Court of Common Pleas—accepted the task of overseeing the child sex abuse trial of former Penn State Assistant Football Coach Jerry Sandusky. Cleland drove the two hours from his home in rural northwest Pennsylvania to Bellefonte, the county seat and geographic center of the state, to meet the courthouse staff. As he made the rounds, the court administrator asked if Cleland might like to drop in on a planning meeting that was just under way.

“And there was this great group of people,” Cleland recalls—court officials, state and local police, the fire chief, reps from statewide media associations. Introductions were made, and then the president of the state broadcasters’ association looked at the judge and posed a question. “We’ve got 32 satellite trucks coming,” he said. “Where would you like us to park them?”

Bemused by the request, not to mention entirely unfamiliar with parking options in the small, hilly, Victorian-era downtown, Cleland wondered why the question was being put to him. “Judge,” came the reply, “somebody has to decide these questions. If you don’t do it, it’s going to be chaos.”

Chaos is not Cleland’s style. In nearly three decades on the bench, he has built a reputation as a firm but amiable arbiter—and, as much as such a thing can be accurately measured, quite possibly the most respected judge in the state. It’s a reputation reflected in his selection to handle the Sandusky case, which—for all the media attention it attracted and the emotions it roiled in the local community—resembled anything but a circus when Cleland’s court was in session.

It’s mid-April, a year and a half later, and Cleland sits now in the living room of the restored 1880s farmhouse he shares with Julie, his wife of 44 years. Steady morning showers have drenched the tree-covered hills of rural Kane, Pa.; you can almost see the land recovering its verdant springtime hue. Kane is Cleland’s hometown, and with the exception of college, law school in D.C., and two years clerking for a federal judge in Pittsburgh, he has lived here his entire life.

The case that brought him some measure of fame has only recently loosened its grip on his world. “Last year was pretty much entirely devoted to Sandusky,” he says. “I didn’t get my last opinion written until February. I just hauled the stuff to the garage the other day.” A return to the routine of custody cases and malpractice suits awaits, as does a more reasonable commute.

Cleland hasn’t previously spoken about the Sandusky trial, and he is cautious as he discusses it now; one gets the sense he weighs his words on the subject as carefully as he weighed the evidence during the trial. It’s not hard to imagine why this thoughtful, deliberate approach made Cleland the obvious choice to handle the Sandusky case after all the eligible local judges—in a county where the local university has massive economic and social reach—recused themselves to avoid any appearance of conflict of interest. “They chose a judge who could focus on the important aspects of the criminal case, be very businesslike about it, and take care of what needed to be done,” says Erik Ross, an attorney who clerked for Cleland out of law school and is now a partner in Cleland’s former firm in Kane. “I thought he was the perfect choice.”

The high-profile nature of the Sandusky trial made it unusual, but the nature of the trial itself was sadly familiar to the judge.

More neutral observers agreed, citing Cleland’s steady, efficient handling of the case, and praising his insistence on ensuring that the process was understood both by the men and women in the jury box, but also by the dozens of reporters conveying the sensitive details to the broader public. Not all of his decisions were unanimously lauded: He memorably ruled that Sandusky’s alleged victims—boys when the crimes were committed, but now adults—would not be allowed to use aliases when they testified in open court. To many, this seemed harsh, but Cleland could rule based only on what the law allows; he softened the blow by urging the media members in attendance not to name the victims in their reporting. It was a suggestion most followed.

Guided by Cleland, the trial came to a relatively quick and tidy conclusion: The jury convicted the 68-year-old Sandusky on 45 of 48 counts, leaving Cleland to hand down what amounted to a life sentence. In his sentencing statement, Cleland addressed Sandusky calmly and directly, telling the now convicted pedophile, “You abused the trust of those who trusted you.” He spoke to the victims, reassuring them that they’d be remembered not for being victims, but for their courage in testifying against the once-respected coach and youth mentor. And in announcing the actual prison sentence—30 to 60 years—Cleland acknowledged that he could have sentenced Sandusky to “centuries in prison,” but chose a shorter, less abstract time frame because it “has the unmistakable impact of saying ‘for the rest of your life.’”

“Cordial, precise, Cleland was the firm hand in control of everything,” Joel Achenbach wrote in The Washington Post after the trial’s end. “He tolerated no distractions or chatter. He radiated neutrality and probity.” Probably more than most men in his position, Cleland appreciates such assessments from the media, whose ranks he once thought he’d join. “I always wanted to be a journalist,” Cleland says.

The son of small-town physicians, Cleland followed his mother, an uncle, and two siblings to Denison, where he majored in history and was an editor on The Denisonian staff. Even then, Cleland was showing signs of being a natural moderator. His roommate and fraternity brother Jim Serianni ’69 remembers “Jocko” Cleland (a play on his skill on horseback) heading up the now defunct Auto Court; later, as president of the student government during the increasingly turbulent late ’60s, Serianni called on his friend for help in bridging the generation gap as he appealed to the administration to adapt to the changing times.

“I was maybe a little bit pushy,” Serianni says, “and I might have alienated some of the faculty. Eventually I had to send John to the meetings in my place; he had such a powerful way of presenting our case, while doing it in a nonthreatening, nonintimidating way.”

Others saw his knack for diplomacy and conflict resolution, but Cleland himself seems not to have recognized the path he was on. Finishing his undergraduate work at a time of growing social upheaval, Cleland says he figured a legal background might be useful in his future reporting career, and he enrolled at George Washington. “I went to law school never intending to practice law,” he says. The newspapers he eventually applied to apparently weren’t convinced. “Nobody would hire me. I think they thought I wasn’t serious.”

Married—he and Julie, a Skidmore grad whom he met at an equestrian competition, exchanged vows in 1969—and in possession of a law degree, Cleland settled into the fallback option that would become his career. He clerked for two years with a U.S. District Court judge in Pittsburgh, then returned to Kane to practice and become a partner at a small local firm. The bench beckoned in 1984, when the local district judge died suddenly. “I never had any aspirations to be a judge,” Cleland says, but he was appointed by the governor, stood for election the following year, and twice won re-election, each time to a 10-year term.

The last of those terms was cut short in 2008, when Cleland was nominated to the Superior Court, a job he held until retiring at the end of 2010, a week after his 63rd birthday. In truth, “retirement” in this case meant a transition to state senior judge, the role in which he still serves, and in which he appears as busy as ever. “Oh, I’m not retiring,” he says when the possibility is raised. “I’m only 65. I still like the challenge of, ‘Here’s a problem—what are we going to do? How are we going to solve this?’”

Certain challenges have demanded more of his attention than others. Cleland has become something of an international expert on the potential impact of a public health emergency on the legal system. About a decade ago, Cleland read of a judge who opened an envelope filled with an unknown white powder. “I called the court administrator and said, ‘If we had one of those, what would we do?’” The response? “Why don’t you figure it out?” And so he did, immersing himself in study, partnering with the CDC and the FBI, and tackling an array of hypotheticals: In the event of a biological attack, who can clear the courthouse? Who has jurisdiction? Can you quarantine people? And how do you keep the system running?

He has written and spoken extensively on the topic, and says he hopes to delve more deeply into it now that the Sandusky case and its lingering post-trial demands are behind him. It’s forward-thinking stuff for a judge lauded for his old-school demeanor and style, but in truth, it fits his career-long habit of looking and thinking ahead. “When I clerked for him, he was all about innovation,” says Erik Ross. “This was 1985, and nobody had computers, but he spearheaded a project to computerize the county judicial offices. He worked on creating a new set of rules for civil matters to manage and expedite the caseload. Pretty groundbreaking stuff.”

“Maybe it sounds clichéd,” Ross adds, “but he’s a big-picture kind of guy. He sees how things fit within the bigger system, and he’s focused on making the system work better.”

In that, Cleland sees a system that too often fails to protect its most vulnerable citizens. “I grew up here, in the country, and then I went on the bench and started handling cases of child abuse and child neglect,” he says. “Even in a small town, a small community, I thought, how could I have been here and not known these things were going on? You feel some obligation to try and change that.”

His biggest—and, prior to the Sandusky trial, most conspicuous—opportunity on that front came in 2009, when Cleland was appointed chair of a special state commission on juvenile justice, formed in the wake of the so-called “kids for cash” scandal that emerged in Luzerne County, Pa. Two judges were convicted of accepting kickbacks from a builder of private detention centers in exchange for imposing harsh sentences on juveniles—many of them first-time, nonviolent offenders—and sending them to the same private jails. Though less viscerally upsetting, the case rivaled the Sandusky saga in its heartbreaking exploitation of children. Cleland wasn’t involved in the criminal trials for that case, but in leading the commission that investigated the systemic breakdown and proposed solutions, he got his chance to make an impact.

“It’s three years ago this May that our report was issued, and they’ve done amazing things up in Luzerne County to reform the system there,” says Cleland. “Could it happen again? Sure. But I hope it’d be a lot more difficult.”

The Sandusky case was in line with the sort of crimes and criminals Cleland has dealt with throughout his career. He compares a judge’s role in the face of such cold, relentless reality to an emergency-room doctor: “You don’t want him to be shocked at seeing blood on the floor.” It would take something drastic to shock Cleland in the courtroom; last summer’s trial in Bellefonte was watched by the nation, and while questions of where to park the satellite trucks, or whether to allow reporters to “live-tweet” the proceedings, made it unusual, the nature of the trial itself was sadly familiar to the judge.

Cleland finds his contentment in many places. It comes from family, the couple’s two grown daughters and three grandkids, including a new arrival in April. It comes from horses, four on their property, his and Julie’s shared lifelong passion. (And for the record: Yes, Cleland once pulled Julie out from under a horse that collapsed while she was riding it at a show; and no, despite what some media reported when writing about Cleland last year, that is not actually how they met. “We were already married at that time, and had two little girls,” he says with a laugh. “I had to pull her out of there, but at that point, it was in my own self-interest.”)

And contentment comes from the process, the one he has spent a career upholding, and on which he is committed to basing every decision. The process is the work; the process is the law, and the law, Cleland says, is “the polestar,” the point of light that never wavers, and that exhorts its practitioners to do the same.