Julia Pandaleon ’27 (Psychology)

Julia Pandaleon ’27 did not expect to spend her first summer at Denison collecting ants in deadwood and observing their behaviors in the lab and their natural environment.

But when the psychology major with a neuroscience concentration saw an opportunity for meaningful research, Pandaleon grabbed a pair of forceps and went to work.

For five weeks, she chronicled the differences in behaviors of social parasite ants and their host ants. Pandaleon was guided by Franne Kamhi, an assistant professor of psychology who’s done extensive research on the social behavior of ants.

Kamhi said Pandaleon’s research offers insight into how the brain works and how a species can adapt to different environments and patterns of social behavior.

Pandaleon developed a jeweler’s touch, using forceps to lift the six-legged buggers into petri dishes. She monitored aggression levels, grooming and feeding habits, and the willingness of ants to communicate with one another through their antennae.

“It’s been fun,” she said. “I’ve learned a lot about the process of doing tests, ensuring their accuracy, and making sure there’s no bias in the testing. It’s been really interesting.”

Betsy Baah ’27 (Biology)

To the uninitiated, the pile of pebbles looks fit for landscaping jobs around the house.

Denison student Betsy Baah ’27 knows better. This isn’t pea gravel. It’s poop, dating to the dawn of the dinosaurs.

Some fossilized pellets may be from dinosaurs themselves, but visiting assistant professor Morrison Nolan in the Earth and environmental sciences department notes they were most likely produced by early crocodile relatives about 200 million years ago.

Regardless of the source, the fossilized feces known as coprolites can yield invaluable information on the physiology of individual animals and the ecosystems of ancient Earth.

As a Summer Scholar, Baah identified and selected samples collected in the Petrified Forest National Park and prepared them for chemical and 3D analysis. The research taught the biology major myriad scientific skills and led her and Nolan to conduct testing on the samples at collaborating labs at Princeton and Virginia Tech.

Not many researchers share this space, Nolan said, which means their findings are truly breaking ground.

“We are on the cutting edge of ancient coprolite geochemistry,” he said with a grin.

“I wasn’t sure I’d get into this,” said Baah, who came to Denison from Columbus, Ohio. “But it’s been really interesting to learn all this about these animals and how they relate to modern animals.”

Abigail Greenleaf ’27 (English)

What goes into creating a modern love story? Abigail Greenleaf ’27 spent part of the summer writing her own with the help of visiting assistant English professor Jennifer Leonard ’09.

“Working with professor Leonard was so much fun,” said Greenleaf, an economics major minoring in creative writing. “It was really nice to be given time to read books and take what I learned and apply it to the story I wrote.”

Greenleaf met Leonard in 2022 at the Reynolds Young Writers Workshop, which Denison has hosted for nearly 30 years. When the first-year student who grew up reading romance novels approached Leonard with the idea, the professor encouraged her to pursue it.

Greenleaf read several books, starting with Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, tracing the evolution of female protagonists.

“With the rise of the modern feminist movement, there’s been a lot more agency given to female characters,” Greenleaf said. ”They have more freedom to live independent lives.”

In other words, Greenleaf’s main character, May, who’s moved to a small town after getting laid off from a big-city marketing job, isn’t searching for her Mr. Darcy to save the family from financial ruin. May adapts to her new surroundings and meets a man who owns a construction company. Both characters work through their own unresolved issues.

Leonard monitored Greenleaf’s progress, reviewing the material in the story and offering insight. They discussed how, in literary fiction, the plot is a function of character rather than a character being a function of plot — as can sometimes be the case in genre romance.

“Abbie brought depth, rigor, and incisive detail to the page,” Leonard said. “I am grateful for the chance to work with — and be inspired by — such a dedicated and intrepid student.”

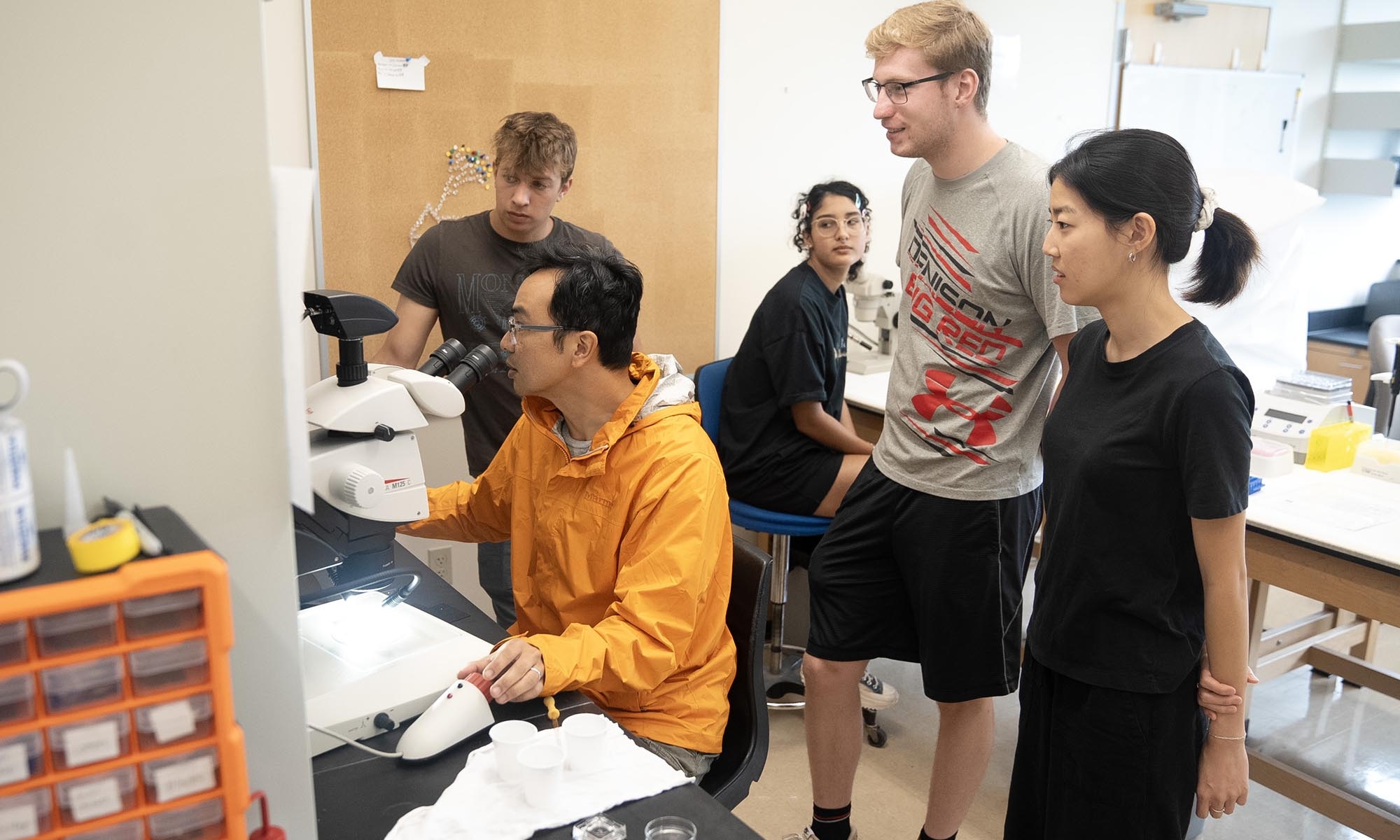

Phil Koutsaftis ’26, Hyangyoo Kim ’25, Ana Pineda ’26, and Tyler Distenfeld ’25

In a Talbot Hall lab, four Denison students spent their summer thinking big about shrimps.

Phil Koutsaftis ’26, Hyangyoo Kim ’25, Ana Pineda ’26, and Tyler Distenfeld ’25 combined their skills in biology and data analytics to delve deeper into the mysterious world of tiny sea creatures known as sponge-dwelling snapping shrimp.

These shrimps, about as big as your pinkie fingernail, are the only marine animals known to be eusocial. Eusocial animals live and work together in colonies led by a queen, much as bees do.

The students worked under the guidance of assistant biology professor Solomon Chak, a leading expert on the fascinating crustaceans and the curator of a massive collection of snapping shrimp species from around the world (read more about Chak’s research here).

At first blush, this research may seem niche, but Chak said understanding the genetics and sociality of these animals can yield much broader scientific insights into evolutionary biology — particularly how and why some species evolved eusociality, in which they have a division of labor in reproduction and cooperate to defend themselves when threatened.

The students, through Chak’s collection, had huge amounts of genomic, morphological, and ecological data at their fingertips, and Chak encouraged them to pursue research questions that personally appealed to each of them.

“We all took it in different directions,” Koutsaftis said.

He and Distenfeld learned a new coding language, and all four students learned to run a laboratory. They also accompanied Chak to the Dominican Republic to collect snapping shrimps in the wild, giving them firsthand experience of the rewards — and challenges — of fieldwork.

“This was a really valuable experience, especially as an undergraduate,” Kim said.

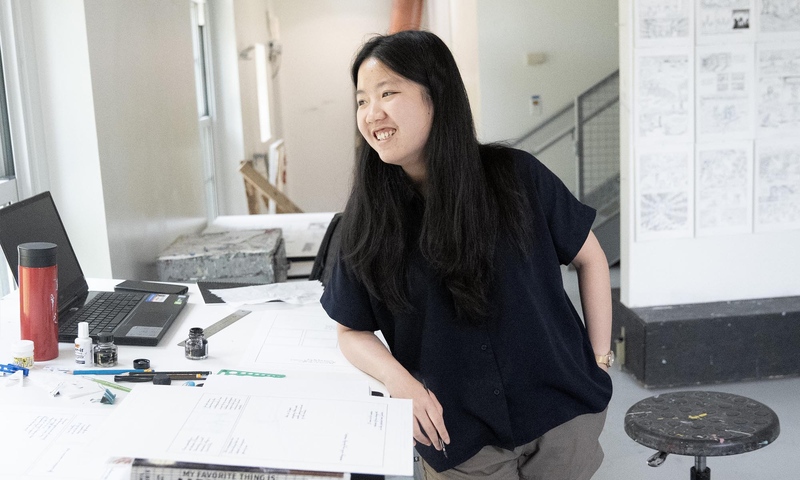

Amy Nguyen ’26 and Ellie Martin ’26 (Visual arts majors)

Amy Nguyen ’26 and Ellie Martin ’26 wanted others to learn about the legends and folklore of their respective homelands.

They spent most of their summer break in a Bryant Arts Center studio, drawing images, writing scripts, and designing layouts to illustrate their stories. Each produced a graphic novel under the direction of visual arts professor Ron Abram.

Martin, a Detroit native, focused her comic book on the formation of Michigan’s Sleeping Bear Dunes, the native legend surrounding it, and her family experiences at the lakeshore park. Nguyen worked on an anthology of autobiographical comics about her life growing up in Vietnam, incorporating Vietnamese folklore she researched for the project.

“This project was my opportunity to introduce some of the well-known Vietnamese folklore to people at Denison,” Nguyen said.

In fall 2023, both students took the professor’s course in contemporary comics — Abram has been teaching it for two decades — and liked it so much that they wanted to produce their own graphic novels.

Martin and Nguyen loved the frequent feedback they received from Abram and the resources made available, including access to the spacious senior studio. Each student planned to self-publish her work.

“I’ve never had this much time to make art,” Martin said. “It’s nice to have the room and flexibility to work on different parts of the book at one time. It’s been a great experience.”

Donna Chang ’26 (Communication)

As a girl in Taiwan and Guam, Donna Chang would accompany her mother on trips to the mall. They would go from store to store, looking at the themed displays that might be trying to sell them beachwear, wedding dresses, or Christmas gifts.

“She really enjoyed window shopping,” Chang said.

Now Chang will view such displays with a more critical eye than ever.

She and her mentor, associate professor of communication Alina Haliliuc, spent much of their summer in New Albany, Ohio, at Easton Town Center, an outdoor mall not far from Denison that bills itself as “the Midwest’s premier shopping, dining, and entertainment destination.”

Easton was built on the idea that consumers would flock to an outdoor, throwback shopping experience like they might have in the retail district of a bustling small town. Twenty-five years later, it remains a draw for shoppers throughout central Ohio.

Chang was intrigued by the developers’ attention to detail in their efforts to sell this narrative to shoppers. She and Haliliuc spent long days recording data including the size of the sidewalks, traffic patterns, location of plantings and park-like spaces, and organization of the many commercial tenants.

“You can tell how carefully designed a place this is,” Chang said.

They watched shoppers in these public spaces, chronicled their interactions, and reviewed existing research on urban planning and similar commercial developments.

“We sought to answer the question, ‘What kind of life is being sold to us here?’” Haliliuc said. “What are they promising, and how are those promises laid down in brick and mortar and cloth?”

There were some revelations.

What they may have found most interesting is that even amid Easton’s contrived world, interactions between people were frequent and authentic. That is no small benefit in an increasingly disconnected and rootless society, they said.

“We were a little enchanted by a sense of playfulness,” Haliliuc said. “There are a lot of what we call ‘Instagram-able places.’ It’s a highly fabricated environment, but it still makes room for a type of public dwelling. It’s a form of place-making in a kind of non-place.”

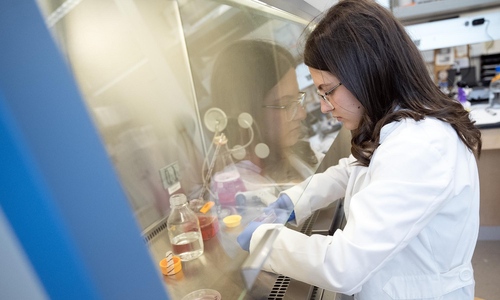

Dea Brahimaj ’26 and Nickawn Namdar ’26 (Biology majors)

They peered through microscopes and witnessed the arc of a cell’s life. They fell into the rhythm of lab work and came to rely on each other’s strengths. They celebrated their successes and shared one particularly crushing setback.

Dea Brahimaj ’26 and Nickawn Namdar ’26 spent their summer working alongside assistant biology professor Cristina Caldari, researching the effects of cannabidiol, or CBD, on fat cells.

CBD is wildly popular among U.S. consumers, marketed as a remedy for everything from anxiety to pain. It has shown real promise in various treatments, but little is known about how it affects fat cells and obesity.

Caldari said some studies have found that CBD can modulate inflammation and fat production in cells, but much remains undiscovered. This line of research is timely and could have real impacts on human health.

“It’s a super-applicable field of research,” Namdar said. “People really care about this.”

The students raised fat cell cultures, introduced CBD to them, and observed what happened.

Their research hasn’t gone perfectly. At one point, their cell samples were contaminated by an unknown source, forcing them to scrap everything and start over. It set them back several weeks and was a major blow for the students, but Caldari said even that was a valuable learning experience.

This is a real lab, she said, not some classroom simulation. Sometimes things go sideways, and you persevere regardless.

“This is the best summer experience I’ve had,” Brahimaj said. “It’s good to know that we’re researching something that impacts people’s lives.”

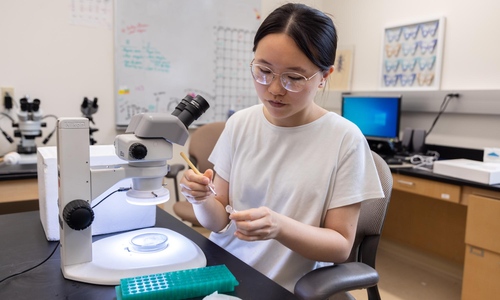

Biana Qiu ’26 (Biology)

Biana Qiu ’26 loves to paint, but she’s not used to working on surfaces as small as the tip of a mosquito’s abdomen.

“It took me 40 or 50 times to get the hang of it,” said Qiu, a biology major.

Armed with a delicate touch, a tiny brush, and a microscope, Qiu contributed to the ongoing work of Susan Villarreal, an assistant professor of biology whose research focuses on insect behavior and ecology.

Qiu spent the summer assessing the mating habits of mosquitoes based on size, large and small. One task was applying fluorescent dye — the kind used in car engines to find leaks — to half the male mosquitoes in the sample group. They were put in a chilled petri dish to temporarily numb them and prevent them from flying away.

After a brief mosquito mating period, Qiu donned a pair of protective glasses and checked under the microscope for fluorescent dye on the abdomen with the aid of a special flashlight. She then performed surgery to determine if the female had sperm. Using the status of the dye for the inseminated females, Qiu was able to assess which male size the female mated with.

The professor was impressed with Qiu’s precision when it came to dyeing, dissecting, and removing reproductive organs with forceps.

“I noticed right away that Biana was very careful with her techniques,” Villarreal said.

Villarreal’s research focuses on the mosquito Culex pipiens, which transmits West Nile virus. The research on mating habits and behaviors helps inform different strategies to control mosquito populations and curb the spread of disease.

“I feel like I’m building on my skills as a scientist,” Qiu said. “I’ve learned so much in this lab that I would not have learned just by attending classes. I was intrigued to work with professor Villarreal because of her passion for the subject.”

Linh Luu ’25 (Economics)

The research that Linh Luu ’25 conducted as a Summer Scholar — an exploration of information theory and its possible applications in economics — is something few others are digging into.

That she is doing it as an undergraduate is nothing short of remarkable, assistant economics professor Pedro Cadenas said.

“It’s rare to see an undergraduate student taking an interest in these topics,” Cadenas said. “All of this, it’s at the margins of the discipline.”

Information theory, introduced in 1948 by engineer Claude Shannon, is a way to mathematically describe the transmission of data and communication of information.

While that may sound esoteric, the principles of information theory led to breakthroughs that have helped drive our current information age, from cellular technology to the development of compact discs.

“Linh discovered the incredible importance that information theory has in today’s world and wanted to learn more about it,” Cadenas said. “Soon we were discussing possible applications to economics.”

With Cadenas, Luu reviewed existing research on information theory and entropy, a measure of disorder in a system. She used data simulations to determine the usefulness of information theory in answering economic questions and also had a test subject in mind.

“I wondered, how can I apply information theory to measure income inequality, compared to other existing inequality measures,” she said. “Inequalities matter … they might impact political representation, health services, and the opportunity to access resources.”

“We thought the best way to start her journey was to frame it in a very narrow form and agreed that she would extend it as far as she wants, based on her curiosity,” Cadenas said.

That was an exciting prospect for Luu, who plans to continue the research as her senior thesis.

Caroline Schumacher ’25 and Junaid Imran ’25 (Physics majors)

First things first. Neither is a dancer.

“I did ballet for like two years when I was 3,” Caroline Schumacher ’25 said.

Schumacher and Junaid Imran ’25 split their Summer Scholars research time between a physics laboratory in Olin Hall and their popup dance studio in Mitchell Recreation and Athletics Center.

“We’re studying a specific jump in Irish dancing, a movement known as a ‘zoom,’” Schumacher said. “While you’re in the air, you do a 360.”

The physics majors found a faculty mentor in associate professor Melanie Lott, chair of Denison’s physics and astronomy department and the author of Biomechanics of Dance.

Lott danced when she was younger, and the physicist carried her love of the art form into her research interest in biomechanics.

More recently, she turned her scientific eye from ballet to Irish dancers, who have been less studied in terms of their biomechanics but are particularly prone to injuries.

In their studio, Schumacher and Imran record their volunteer dancers using body sensors, six cameras, and other sophisticated equipment.

“We collect data from every single one of the dancers’ movements,” Imran said.

Back in the lab, they crunched the data and used it to create computer animations of each jump. They studied the dancers’ horizontal and vertical movements, the twisting motions they employ to rotate while airborne, and the forces exerted on their bodies from start to finish.

Their findings might inform better Irish dance instruction but also can yield broader insights into injury prevention.

The study has introduced them to the breadth of scientific research, from fieldwork to data analysis.

“I’m asking them to do a lot, and they’re doing it,” Lott said.

Haimanot Assefa ’26 (Global health)

The road to discovery can be a long one. In the case of Haimanot Assefa ’26, it involved a data set of 13 million hospital patient discharges.

The global health major spent her summer researching whether socioeconomic status explains the racial disparities in postoperative hysterectomy complications for women with endometriosis.

It was an ambitious project, one aided by the guidance of associate global health professor Ehab Farag.

While taking a Global Health 100 course, Assefa learned about endometriosis — a painful condition in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus.

“It really piqued my interest,” Assefa said. “Certain races are more likely to get surgical complications after a hysterectomy. But I couldn’t find any article that showed why.”

She contacted the National Inpatient Sample, the country’s largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database, and received voluminous 2020 and 2021 reports for a $300 fee. The student had no previous experience with statistical analysis, but Farag helped her set parameters that whittled 13 million discharges to about 6,000 involving women with endometriosis-related hysterectomy complications.

Assefa worked about seven hours a day for 10 weeks on her project. The professor taught her how to employ mediation analysis to factor in race/ethnicity, complications, median household income for patients’ ZIP codes, and primary insurance status. They also worked together to select and control for 10 variables, including age, length of stay, and hospital networks.

Her research suggests socioeconomic status does not contribute to the racial disparity in the outcomes. But without pertinent information on patients’ education and occupation types, she believes her findings remain incomplete. Assefa hopes to add that material to her ongoing research.

Ten weeks of hard work did lead to one definitive conclusion.

“I like doing research — that’s what I’ve learned,” said Assefa, who’s on a pre-med track. “I like figuring things out and putting the pieces together.”

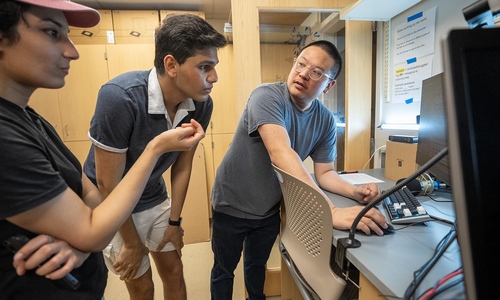

Shaina Khan ’25 and Aryah Rao ’26 (Computer science majors)

The furrowing of eyebrows. The tilting of heads. The touching of lips or other parts of the face.

How do you spot signs of confusion? And, just as important, when is the right time to offer assistance?

These are the questions Shaina Khan ’25 and Aryah Rao ’26, a pair of computer science majors, are looking to answer. They spent months, including a good portion of the summer, researching how people express confusion while performing small cognitive tasks.

It’s all part of a long-term project under the direction of computer science assistant professor Matthew Law.

“We want to understand what it looks like when a person is working on a problem, and they reach an impasse, and they may want help,” Law said. “The objective is to create more timely, proactive help. The counterexample is a digital assistant that’s always asking, ‘Do you need help?’ over and over again. That gets really annoying.”

Khan and Rao invited fellow students to Ebaugh Laboratories to participate in a study using cameras, computers, puzzles, and games. Students were given three puzzles to solve, with a 10-minute time limit for each. The researchers focused on the subjects’ facial expressions, body language, and speech.

After completing the tasks, the subjects watched replays of their work and explained what they were feeling as their expressions and body language changed.

“We look for patterns,” Khan explained. “It involves lots of data collection. We look for particular body language and make sure we know what the students are experiencing in the moment so we can collect the most accurate information.”

The research is ongoing and part of a collaborative effort with students and professors from Cornell University, where Law earned his doctorate in information science.

“Their big-picture goal is to support future development of predictive models that enable timely and relevant proactive help from digital assistants,” Law said.