Dave Abbott ’74 & Jan Roller ’76

Sitting in a downtown Cleveland restaurant, about a mile from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, Jan Roller ’76 tells the story behind her husband’s Bob Dylan-inspired music video to promote his 50-year class reunion.

Dave Abbott ’74, seated across from his wife, laughs at the memory of donning a jean jacket, wig, and pair of shades while singing Denison-centric lyrics to the tune “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” The co-chair of the reunion committee even made flashcards with buzzwords from the song, just as Dylan had for his iconic black-and-white video.

“Jan filmed it on her phone, and our middle son, a production manager in animation for Warner Bros., did all the editing,” Abbott recalls. “It was fun, but flipping those cards in time with the music was really hard.”

He’s not sure how he landed on the idea, only that the alumni office asked him to make a video urging classmates to attend the milestone event. Abbott wasn’t about to disappoint a university that transformed his family’s life.

“I enjoyed Denison, but it wasn’t my best four years because I was lucky enough to work at jobs I really enjoyed,” Abbott says. “As time goes on, I’ve appreciated Denison more because I recognize the impact it’s had on us. It’s made us see possibilities and how to attack those possibilities and make them realities.”

Cleveland’s power couple

Roller is a well-respected trial lawyer, a tireless champion for civil rights, and a civic leader who’s sat on prestigious boards, including serving as past president of The City Club of Cleveland — the community’s citadel of free speech.

“Denison opened the world to me, period,” says Roller, who fought for women’s equality while working in a Massachusetts district attorney’s office. “It gave me my first female role models. It provided that liberal arts education, that curiosity, that broader breadth of knowledge that allows you to move confidently through your life.”

Abbott has worked as a Swiss Army knife for his adopted hometown, occupying various prominent roles in helping Cleveland emerge from its darkest days in the 1970s and assisting in its cultural renaissance two decades later.

As a Cuyahoga County administrator, he played a vital part in the Gateway project that delivered new stadiums for the Guardians and Cavaliers in the 1990s and kept Major League Baseball in Cleveland.

The civic entrepreneur was the executive director of the Cleveland Bicentennial Commission, the president of an urban renewal organization that transformed University Circle neighborhoods, and the president of the philanthropic Gund Foundation — a vehicle for social change.

In the late 1990s, Abbott even served as director of the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, where his kindred spirit, Dylan, was enshrined in 1988.

“Denison teaches you to be a lifelong learner and a problem solver,” Abbott says. “Those traits have been invaluable in my career.”

‘Quality of teaching sticks with you’

Roller began dating her future husband in high school, and their relationship blossomed at Denison, where they both majored in political science. After, they attended law school, although Abbott worked as a newspaper reporter in Cleveland for several years before enrolling.

At Harvard Law School, Abbott’s appreciation for Denison began to grow.

“The quality of teaching at Denison was so much greater than it was at Harvard Law School,” Abbott says. “The law school hires brilliant scholars who are experts in some esoteric aspect of the law, which is fascinating, but a lot of them cannot teach as well as the professors at Denison. That quality of teaching sticks with you, and from what I know, it’s only gotten better.”

At his 50-year reunion, Abbott earned praise from fellow alums for his parody video. Turnout was great, and talk of their time on campus supplied plenty of laughs. But Abbott noticed that classmates he engaged were less interested in reliving their Denison glory days and more focused on how their time on The Hill set them up for success.

“There was some reminiscing and telling crazy stories that I had forgotten,” Abbott says. “I thought there would be more of that, but it was really about what we have been doing and what we’ve accomplished since leaving Denison.”

Martha Kimball Cathcart ’74

Martha Kimball Cathcart ’74, a professor emerita of molecular medicine at Cleveland Clinic, enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a scientist, educator, and trailblazing role model.

Cathcart is internationally renowned for her research, and she’s traveled the globe speaking at prestigious conferences.

While discussing her Denison education and the intellectual horsepower it provided, Cathcart cites a discipline not involved in scientific study. The power of the pen.

“Scientists have to be excellent writers, and that’s something that often gets overlooked in their training,” Cathcart says. “You have to be able to write manuscripts and apply for grants that fund your research, and you have to do it in a way that can be understood. I didn’t appreciate it at the time, but a liberal arts education taught me this important skill and facilitated my career in research.”

In addition to running a research laboratory, Cathcart was involved in graduate and medical education. She served on the committee to form a new medical school at the Cleveland Clinic.

“A liberal arts education taught me this important skill and facilitated my career in research.”

As a professor, she applied for and won a grant from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in 2006, which has funded the school’s novel graduate program in molecular medicine. The Cleveland Clinic was one of just 13 institutions to be awarded the inaugural four-year grant.

She later renewed that grant and submitted the Howard Hughes-funded program for grant support from the National Institutes of Health. That federal funding continues today.

Cathcart has been a tireless advocate for medical and graduate students. She is the daughter of the late Rolla Grattan Kimball, an Upjohn researcher who helped increase the supply of penicillin for American troops fighting in World War II.

“I emulated my mother,” Cathcart says. “She was a chemistry major at a time when very few women were in the field.”

Cathcart has championed the cause of women advancing their careers in scientific research. She remains the only woman not a medical doctor to serve on the Cleveland Clinic Board of Governors.

At national and international conferences, fellow women researchers express their admiration and gratitude for Cathcart’s efforts. As a young scientist, she recalls older women in the field “taking her under their wing” at national meetings.

Fifty years after graduating from Denison, she also pays tribute to her former biology professor Philip Stukus, who fueled her love of research.

“What I took from that time was the importance of applying yourself to a problem, owning it, and becoming an expert because you’re at the forefront of knowledge,” Cathcart says. “I embraced that approach, and I practiced it my entire life.”

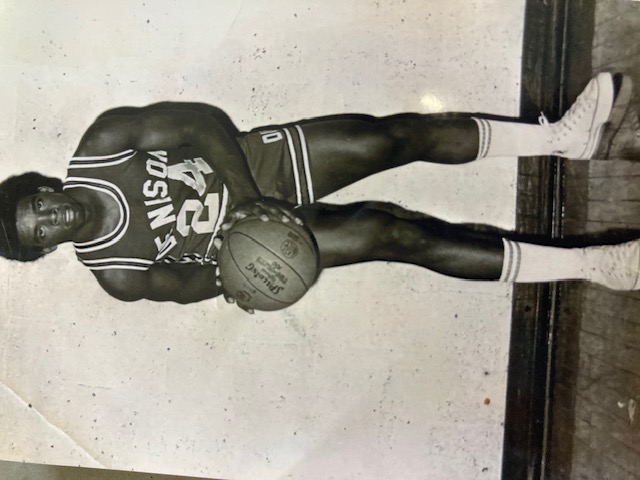

Dudley Brown Jr. ’74

“Denison taught me that it didn’t matter where you came from, it’s all about where you are going.”

Dudley Brown, right, with friend Henry Wilkens at a community event in Evanston, Illinois.

If anyone at his 50-year reunion could have made the case that Denison was the best four years of his life, it was Dudley Brown Jr. ’74.

Brown starred on the men’s basketball team, finishing his career as the program’s third all-time leading scorer. Remarkably, he remains the Big Red’s 10th leading scorer despite having played in an era before the 3-point shot.

“I didn’t know this stuff until my daughter alerted me to these facts in 2014,” Brown said.

This is Brown’s humble way of saying athletic fame didn’t define him at Denison or in the years after he left The Hill.

The Toledo, Ohio, native enjoyed a long and productive career in finance — and his time at Denison set him on the path to success.

“I loved my time there, but I had a goal in mind,” Brown said. “Denison taught me that it didn’t matter where you came from, it’s all about where you are going.”

Brown turned down an athletic scholarship at Western Michigan University because it didn’t have the academic pedigree of Denison. He majored in economics and spent three summers working in a Columbus, Ohio, bank chaired by Denison benefactor Don Shackelford ’54.

Shackelford served as an important role model for Brown and William J. Harris ’74, a Big Red teammate who also worked summers at the bank.

Brown recalls Shackelford taking him to lunch and explaining how to grow a business. Inspired by the mentorship, Brown attended the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University before launching into a career in finance.

“I didn’t know what a certificate of deposit was,” Brown recalled. “I didn’t understand the idea of mortgages and how homes were valued. Those three summers at State Savings Bank were my introduction to the world of money and finance. It led me to think this is the arena I want to be in for the rest of my life.”

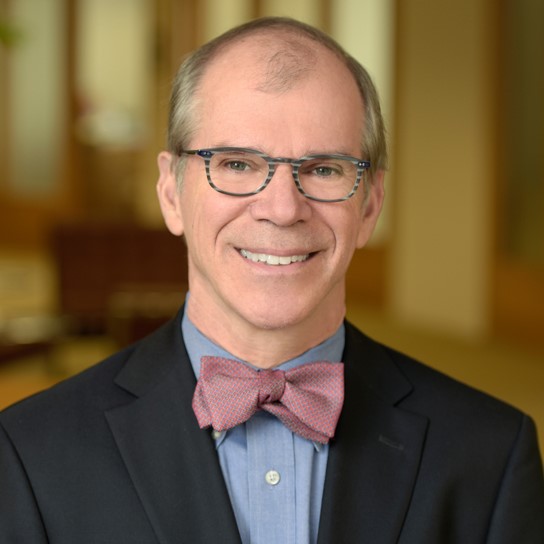

Dean Hansell ’74

“I developed empathy and the ability to relate to many different types of people at Denison.”

Los Angeles Superior Court judge Dean Hansell ’74 got married for the first time two days after his 70th birthday.

“My husband is an actor, and his acting studio has the motto ‘Dreams have no expiration date,’” Hansell said. “That proved to be the case for us. Being married is a new journey.”

At an age when most are reflecting on their life’s achievements, Hansell is still out there achieving. He was appointed a superior court judge at age 64 and recently became a grandfather.

Hansell can’t wait to see what tomorrow brings.

“I’m not sure what my expectations were after graduating from Denison, but I’ve been fortunate to have a lot of remarkable experiences,” said the founder of the Los Angeles chapter of the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation and the vice chair of the Library Foundation of Los Angeles, which has more than 70 libraries.

Hansell acknowledges one of his best decisions was enrolling at Denison at a time when his parents wanted him to attend Northwestern University, where he had been accepted. (As it turned out, Hansell went to law school at Northwestern after Denison, so everyone in the family got to claim victory.)

But Hansell smiles with satisfaction when revealing that his parents eventually conceded he made the right call coming to The Hill.

Denison instilled in Hansell a curiosity that continues to serve him as a judge. The university’s environment also played a key role in his career arc.

Before his appointment as a superior court judge in 2016, he was an assistant attorney general for the state of Illinois, a prosecutor for the Federal Trade Commission, and a partner in several large international law firms. He sits on the law board of Northwestern’s law school.

Hansell works in a metropolitan area of more than 12 million residents and estimates legal briefs have been filed in his court in more than 30 languages.

“Every day you meet different people,” Hansell said. “I developed empathy and the ability to relate to many different types of people at Denison. A small residential community does that. Had I gone to a larger school, the inclination probably would have been to self-segregate into groups who were just like me.”

Hansell’s appreciation of diversity includes his taste in fashion. The judge owns more than 100 bow ties. He brought several with him to his 50th class reunion, which he co-chaired with Dave Abbott ’74.

At age 72, Hansell shows no signs of slowing down.

“Working on the reunion committee was such a treat,” he said. “We’re already looking forward to our 55th reunion.”

Robert Knuepfer ’74

Denison promotes the value of being a lifelong learner, of never retiring your curiosity or idling the desire to discover new passions.

Robert Knuepfer ’74 embodies those ideals. At age 64, after a long and distinguished career in mergers and acquisitions, Knuepfer enrolled at the University of Chicago Divinity School to pursue a master’s degree in divinity.

“I became an ordained minister in the United Church of Christ, atoning for my prior sins as a lawyer,” he joked. “It might take the rest of my life to get even.”

Surrounded by students in their 20s, Knuepfer studied ancient Greek and Hebrew to read the scriptures. After 38 years as an international partner at Baker & McKenzie LLP, he found himself working as a chaplain in the emergency room and intensive care units of Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.

“I would have one hand on a gunshot wound and the other hand on a Bible,” he said.

Knuepfer treasured his time at Denison, serving as Alpha Tau Omega president and interning at the White House on an ATO scholarship. But it’s the overarching lessons he gleaned from The Hill that made the rest of his life so fulfilling.

“Denison teaches you to take chances, to explore new ideas,” said Knuepfer, who earned a doctorate at the Chicago Theological Seminary. “It’s OK not to know everything — just open your mind to learning.”

Knuepfer serves as an associate pastor at the Union Church of Hinsdale, Illinois. The father of four laughed as he recalled telling his wife about his stunning career pivot.

“I wish I had a great story like Martin Luther being knocked off his horse by a lightning bolt,” he said. “There was always a knock on the door. I was slow to answer it, but I finally did. It was a function of significance and helping people with their spiritual life.”