Leaping from the home nest to the independent life of a college student is exciting but it brings new challenges and self-management responsibilities. If that student has ADHD, the transition can be daunting. The old understandings about ADHD as a behavior disorder are no longer tenable and for many years it was essentially considered a disorder of childhood. Research in the last decade, especially from neuroscience and brain imaging, have helped people to understand ADHD as an unfolding developmental pathway and not just a static disorder. Many of these impairments can continue into college and adulthood.

To that end, professionals from the Whisler Center for Student Wellness (WCSW), Sanda Gibson, and Jennifer Vestal from the Academic Resource Center (ARC) decided to pool their respective resources. They created a psychoeducational/skill building group that helps students with ADHD to develop habits and strategies to function in academia. “Many students still don’t understand the diagnosis and they often experience an internal sense of frustration and failure,” says Gibson, a mental health counselor. She adds, “We help them understand this is a brain-based diagnosis that affects executive functions. In college, executive function deficits show up in behaviors such as disorganization, chronic lateness, forgetfulness, sporadic attention to classroom activities, uneven academic performance, sleep difficulties, relationship difficulties, and poor time management. It can be very overwhelming and discouraging.”

Vestal, a learning specialist, remarks, “In addition to psychoeducation, we try to teach them skills and strategies that aid in time management, organization, goal setting, self-advocacy, and resilience.” Each week students reflect upon their own unique challenges and set specific goals for change. Group leaders offer support to help them execute these tasks.

“We try to teach them skills and strategies that aid in time management, organization, goal setting, self-advocacy, and resilience.”

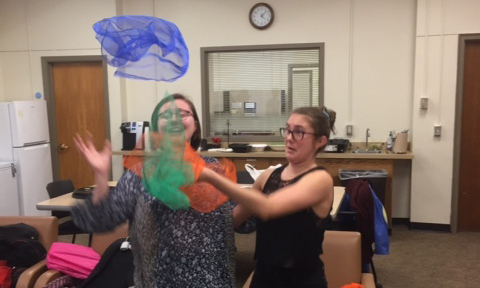

Gibson and Vestal both believe in a strengths-based approach and they emphasize the unique strengths of students with ADHD such as intelligence, creativity, multitasking, and the ability to think outside the box. They utilize a variety of tools to help students manage stress and calm their brains such as juggling, art activities, and mindfulness activities. For example, fellow Denisonian Edith Keme ‘18 visited the group and taught juggling skills she learned in CircEsteem, a Chicago circus arts program for youth development.

It can also be helpful for staff and faculty who are open to self-disclosing about their own ADHD diagnosis to share their stories. “We think these role models are so important so they feel less angst about their own symptoms and can visualize their own future success,” says Gibson. In addition to role models, peer support has been an important piece of the program. Vestal adds, “It is also gratifying to see how the students reach out to one another on their own. In the past, they have set up study tables or created group texts to encourage one another and stay in touch.”

A diagnosis of ADHD is not a requirement for participation. And this group is not for everyone. Some students with a diagnosis already have learned skills and strategies prior to high school that serve them well. But it is another form of support that utilizes the power of group work and the collaborative strengths of two different departments. Interested participants are encouraged to try the group at the beginning of each semester.

The number of students is limited to around 12 and the group is “closed” after a few weeks so the group can feel more connected. As Vestal observes, “We look at outcomes. Perhaps even more than the skill-building and staff support, students value having a safe place where they can vent a little, relax, not feel judged, and just be in a welcoming place each week that is special just for them.”