We live in an amazing age. In the past few years alone, scientists have developed a way to print functional three-dimensional objects, discovered the existence of a “God Particle,” and landed a robot on the surface of Mars. Yet, despite these incredible achievements, we still know surprisingly little about how our own brains function, according to Lyric Jorgenson ’00, health science policy analyst with the National Institutes of Health.

For Jorgenson, this lack of understanding presents an incredible opportunity, and she’s devoted her career to the study of the brain with the hope of both illuminating its intricacies and also finding preventions and cures for its disorders, such as epilepsy, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

“I’ve always known from the start I wanted to do something that would help people’s health,” says the Wisconsin native who was raised in West Virginia and Illinois.

Last spring, President Obama announced the BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative, a bold new effort to unlock the mysteries of the brain. This initiative aims to accelerate how brain cells communicate –all at the speed of thought. Similar to the Human Genome Project, the BRAIN Initiative’s purpose is to bring together and support some of the smartest people in the world as they attempt to shed light on a largely unknown area of scientific study to improve human health.

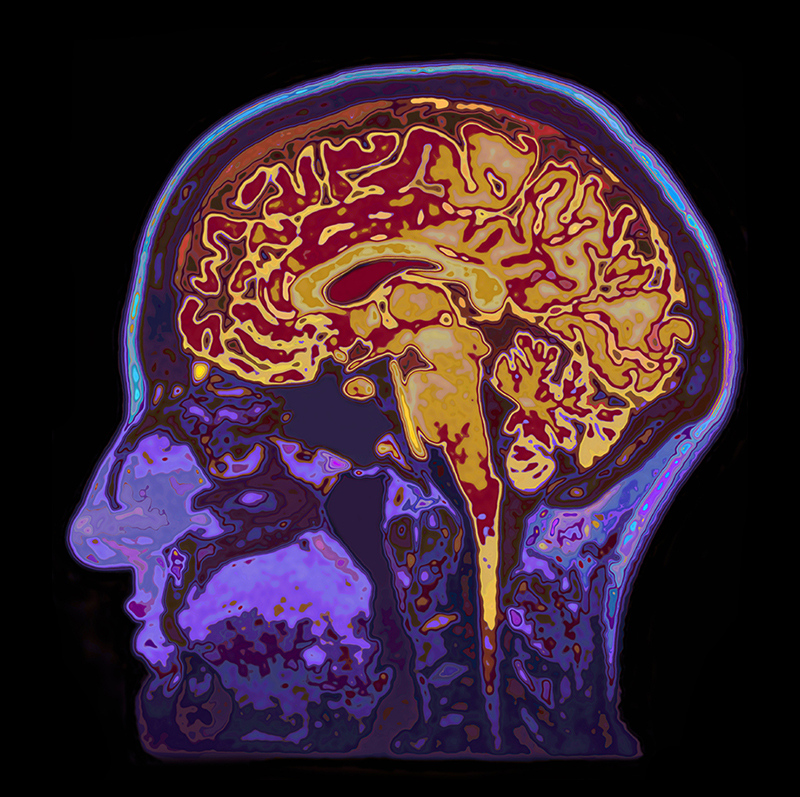

“It’s important to understand how something works before you try to figure out what goes wrong with it,” Jorgenson says. That’s a tall order considering the average human brain consists of nearly 100 billion cells, which transfer signals and information via roughly 100 trillion connections. With that many processes taking place at any given time, it’s no wonder the scientific community has been routinely hindered in its pursuit of unlocking the brain’s many mysteries.

Jorgenson, who lives and works in the Washington, D.C., area, currently serves as the NIH staff lead for the BRAIN Initiative, writing reports, briefings, articles and fact sheets for Congress and the White House, as well as federal agencies, nonprofits and the general public. The 35-year-old recalls the thrill of being asked to fact-check a copy of President Obama’s speech on the initiative. Having it pop up in her email inbox, she says, “was the coolest thing ever.”

Jorgenson says her love of neuroscience started at Denison—and her love of Denison started the first moment she stepped on campus. “The small class size and interactive nature of the classrooms made it much more appealing than other schools I visited. The campus really feels like a community, which was important to me.”

Jorgenson initially pursued a degree in English, however an Introduction to Psychology course taught by Dr. Susan Kennedy prompted a complete turnaround.

“You cannot help but be mesmerized by the brain after taking her classes,” Jorgenson says. “That, coupled with the fact that understanding how a human being thinks, feels, acts and remembers might be the most fascinating subject ever, made it easy to want to learn more.”

Upon graduating from Denison, Jorgenson attended the University of Minnesota, where, after getting her Ph.D in 2005, she remained as a postdoctoral researcher, studying the development of the hippocampus, a part of the brain that deals with memory and navigation. Her research earned her a highly competitive fellowship with the American Association for the Advancement of Science, through which she secured a high-level science policy position in the Office of the NIH Director.

Aside from her extensive studies in the field of neuroscience, Jorgenson has relied heavily on her capacity to relay in-depth scientific concepts into layman’s terms.

“There are a lot of diverse perspectives you have to think of when you’re forming policy,” she says. “I would say that my ability to interpret, synthesize and communicate complex information is key to my current position—a skill greatly enhanced throughout my coursework and interactions with faculty. Denison does an amazing job challenging students to think critically.”