I was not prepared to visit the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in downtown Montgomery, Alabama, earlier this month. I had watched news stories about the memorial, visited its website, and talked at length with my colleague Lauren, who grew up in Montgomery and had visited the site last year, not long after it opened to the public. And still, I was wholly unprepared for the horror and grief inflecting nearly every aspect of one of the most compelling, evocative, and effective memorials recently created. To walk along the memorial’s grounds is to reckon with a past where thousands of black bodies had been brutally terrorized and murdered. And my reckoning also concerned the future: Amidst the grief and pain, what difference can our teaching really make?

Opened in 2018, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is the first of its kind dedicated, as literature about it reads, “to the legacy of enslaved black people, persons terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence.” Set on a carefully manicured six acres, the Memorial uses sculpture, literature, poetry, and design to render in heart-wrenching terms the violence and terror of racial oppression. This effort to remember rightly was realized through painstaking labor by the Equal Justice Initiative, a private, nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide legal representation to indigent defendants and prisoners denied fair and just treatment in the legal system. Researchers with EJI spent years verifying and documenting the names of over 4,000 African American men, women, and children lynched between 1877 and 1950.

With over 800 steel monuments containing the names of counties across the United States where lynchings took place, along with the names and dates of the murdered, moving through the memorial is both arresting and emotionally and morally exhausting. In confessing that exhaustion, I do not pretend that the grief I felt matches in any way the grief, frustration, and anguish other visitors experience, particularly those who feel kinships of blood and memory I will never know.

If the memorial evokes grief, frustration, and pain, these are not the only feelings it perpetuates. Before encountering the hanging steel columns, visitors walk along a path marked by sculptures depicting the horrors of slavery and the solace found in words of courage and resistance. A garden overflows with flowers and life and the renewal of spring. As I made my way into the memorial itself and began to move among the columns that met me at eye-level, as I read and tried to comprehend the names and dates—so many names, so many dates—I had to stop and collect myself; the emotion was overwhelming, the reckoning visceral, softened only by the sound from a water wall on which reads the inscription, “Thousands of African Americans are unknown victims of racial terror lynchings whose deaths cannot be documented, many whose names will never be known. They are all honored here.”

If the force of the reckoning is amplified by the memorial’s design, it nonetheless remains true that reckoning with the past leaves visitors acutely aware of the unfinished work which remains: Racial oppression continues in unjust legal machinations and an industrial prison complex about which the United States should be morally ashamed. For me, then, the reckoning is two-fold: I am haunted by my obligation never to forget, and I am burdened by whether our teaching will make any difference in this contemporary moment. Amidst the names and dates and memories, what is education really for?

The question, I think, is answered in part by remembering that our learning spaces have never existed in vacuums. To teach is, every day, to come to terms with the frailty of our students and ourselves, to realize that the best designed lesson plans and assignment hand-outs cannot answer everything, that certain legacies are so fraught with mourning and with loss that the best we can hope for is to cling to hope. This hope recognizes full-face the unabashed existence of grief, pain, loss, and the unchecked violence of racial oppression, but insists that a way through nevertheless exists. That way through will not be easy, and will depend, in part, on equipping our students not merely with the bones of our disciplines, but also exposing them to the soul of our professional identities, ways of working and being which hinge on intellectual virtues like generosity, curiosity, compassion, fierceness, and, yes, even love.

But maybe the equation is simpler than the way I’ve sketched it above. On the shuttle ride to the memorial I sat with Charlie, an African-American grandfather in his mid-60s. He talked with pride about his grandchildren, whom he loved deeply and who also were bi-racial. “Hate simply can’t live in them,” he insisted to me, “because they have both of us in them. You and me,” he continued, “there’s so much we have in common, and my grandkids remind me that the world is going to get better.”

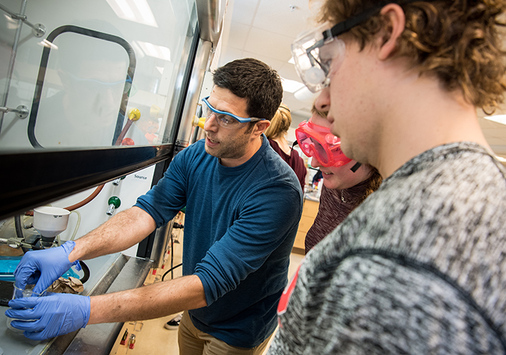

I want to believe Charlie. I need to believe Charlie. And maybe I need to recognize, too, that belief isn’t enough. I must do something. Where to start? The studio, classroom, and laboratory seem like fitting places. There we might inspire our students to work across differences, to see in the faces of others a common humanity and urgent dignity, to approach the past and the present from places of profound humility, because at day’s end we never can know all that we ought. And I like what Lauren wrote, after she visited the memorial last spring: “Make the effort to come to Montgomery. Bring your families, your friends, your students. Learn these names [inscribed in the Memorial] and tell their stories. Answer your kids’ questions truthfully.”

We are linked together by obligations so much greater than ourselves. If Denison will continue to thrive as a culture of learning and teaching, we must strive to remember how much we need each other as we do this shared work. We must acknowledge each other, every day, and tell the truth. We must, finally, teach from places of unshakeable bravery and conviction that our work matters. We owe that much to the dead. And to the living. As W.E.B DuBois prayed, it is never too late to mend.