10,000 Acres, a multimedia documentary by videographer and journalism professor Doug Swift, explores some of the major themes of our nation’s history.

Focusing on a small corner of Appalachia, Swift compiles a big story, researching and documenting Indigenous peoples, pioneer tribulations, effects of the industrial revolution, and more, up to and including a conservation camp held just this summer.

“The whole story is about the human relationship to the land, as it evolves from the beginning to today. If I’m successful, you can feel that relationship, from the first Native Americans to the people who manage giraffes and rhinos at the wildlife sanctuary,” says Swift, who has been “circling around this story for more than 10 years — and actively working on it for two.”

He unearths an unexpectedly rich source of material in a 10,000-acre reclaimed strip mine located in southeastern Ohio. In Michener-esque style, Swift illustrates the geologic processes that formed its rich resources, then chronicles the people who lived in relationship to the land over centuries, including the caretakers of the zebras that now roam these Ohio hills.

Along the way, 10,000 Acres pays homage to the Adena culture via a burial mound that still exists on the property, saved from strip mining by a gas line. Pioneer-era histories follow, stopping for a long moment on the Lett Settlement, a community of mixed-race farmers and tradespeople.

Members of this community had to sue for the right to educate their children, and to vote, setting important civil rights precedents, Swift says.

Industrial revolution demands and population booms fueled the strip mining that leveled these Appalachian foothills to expose underlying coal. The process removed thousands of acres of topsoil from once-fertile farmland. This is where Big Muskie, the largest dragline excavator ever built, removed twice the amount of earth moved during the Panama Canal construction.

The mines left behind impoverished soils, toxic waters, and a devastated landscape, before an Ohio law and subsequent federal reclamation act sparked yet another iteration of the land.

Today, these 10,000 acres are bringing new riches to the area via a steady stream of tourism. The Wilds, a private, nonprofit conservation center, devotes 1,500 acres to accommodate more than 500 animals representing 28 rare and endangered species, and manages the grassland and forest ecologies of the 8,000-plus remaining acres.

Contributions from artists, scientists, and journalism students

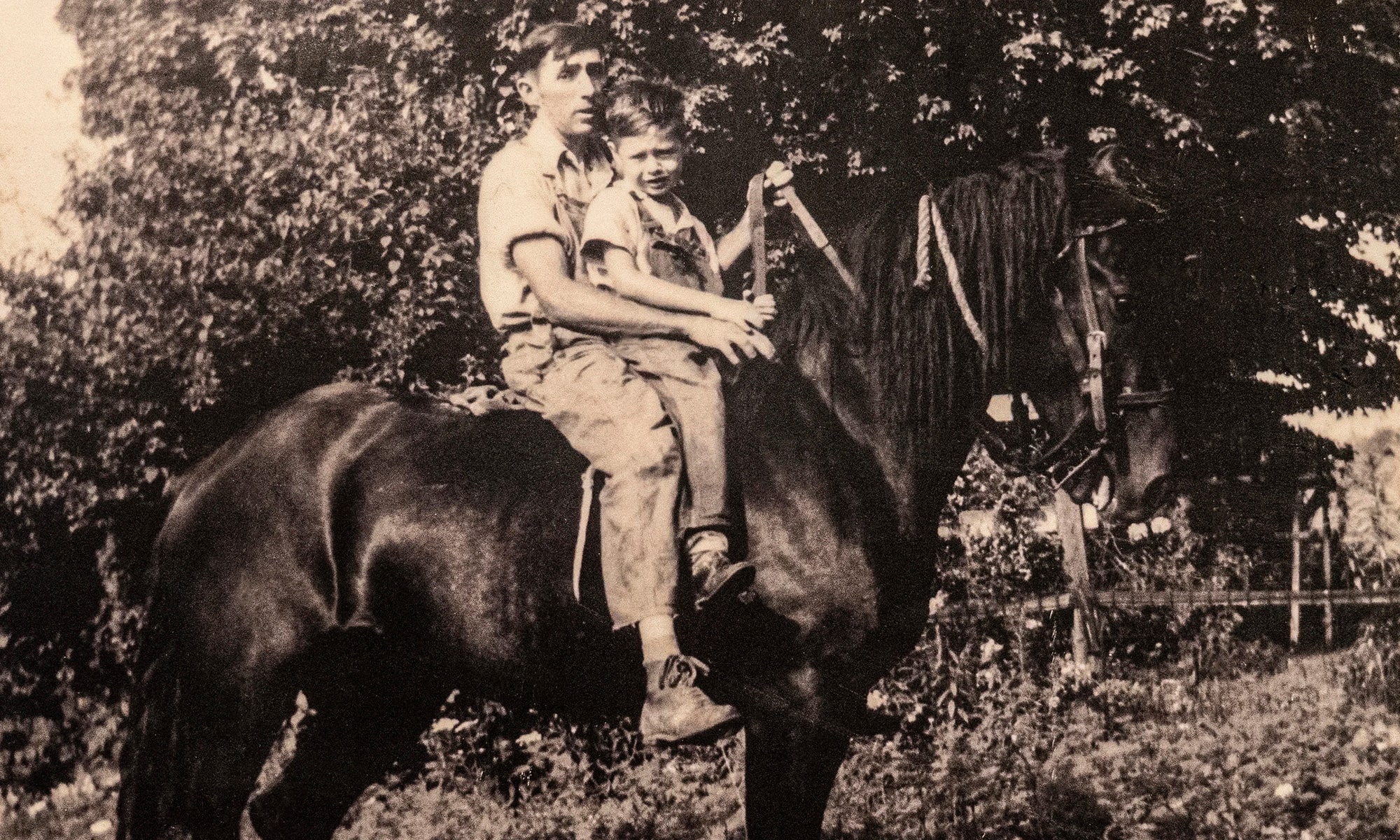

10,000 Acres serves as a historical document — a testament to the land and those who lived and worked there. Firsthand accounts are supported by photographs, informational graphics, video, and audio clips sourced from personal collections. To tell a tale this big, Swift needed many helping hands.

Denison earth sciences professor Erik Klemetti and environmental studies professor Doug Spieles contributed their expertise. Artist Mary Ann Bucci provided illustrations. Composer Matt Jackfert knit the documentaries together through a unifying score. Journalism students from Denison and West Virginia universities added narratives and documentaries.

Each chapter is developed in the storyteller’s milieu — documentaries, short films, and longform journalism. These are not biographies of the wealthy people and companies who bought and sold the land. These stories focus on the people who lived and worked on the land.

Sarah Hume ’22 wrote about mine employee Jerry Few, a welder who maintained the Big Muskie excavator and other equipment. Stricken with Black Lung disease, Few could only communicate with Hume via text and email. Hume writes:

“I am like a dog on a chain… Only if a dog breaks its chain it runs away. If I break my hose, I eventually die.”

“Even with Black Lung, Few tells me, he wouldn’t trade his time on the Muskie for anything. He loved it. He loved the people. They were family.”

Hume’s extensive profile was published in Belt magazine. Few was impressed that Hume captured his truth, as complex as it was, saying he would print the article and “put it in my coffin to go with me.”

The beating heart of 10,000 Acres

The Wild’s grassland and forested preserve has seen successes and challenges. While grasslands are not a naturally occurring habitat in Ohio, many species of birds accustomed to this environment have migrated here. Flocks of bobolinks and Henslow’s sparrows are thriving in their new home.

“I feel the birds are the beating heart of 10,000 Acres,” Swift says. “You might go out there now and see barren green hills. But if you walk into the hills, you see all these amazing birds — a real tapestry of life.”

However, that tapestry is now under threat from yet another human intervention. Autumn olive, an unprepossessing shrub imported from Asia, was planted in the 1990s to stabilize the soil. Today it is classified as invasive. And it is fast encroaching on the grasslands.

Few resources are available to combat the invasion, but local biologists are observing and researching the bird populations there. The hope is research will offer new avenues to save the grasslands.

“We’ve done all this stuff with good intentions, but we have lived as if we could impose our will on nature,” Swift says. “We humans see time as a fixed thing, and when things start to shift or change we perceive that something is wrong. But the arc of this story shows that these changes, which are happening faster and faster, indicate if we want to have a relationship with nature, we will have to make a reckoning with it.”