A sign that hangs on the office wall of professor David Goodwin, chair of Earth and Environmental Sciences, offers a glimpse into his worldview.

Life is a journey, not a guided tour.

Celebrating his 20th year on Denison’s faculty, Goodwin continues to encourage students to explore their surroundings and boundaries and to remain intellectually curious.

“I tell them, ‘I don’t really read a lot of fiction because the world is so interesting the way it is — just go see it,’” Goodwin said.

In the name of science, the professor has led field study all across North America and parts of Europe. He’s taken students to England, along with English professor Fred Porcheddu-Engel, to examine the life, death, and legacy of Richard III.

Back on campus, Goodwin has overseen the rebranding of his department from Geosciences to Earth and Environmental Sciences, which debuted in fall 2021. Its central goal is to educate students about the nature and history of the Earth, the processes that shape the planet, and the impacts those processes have on humans, other organisms, and the environment.

The rebrand has produced the desired effect with a dramatic increase in student interest, including a growth in the number of majors.

A man of many interests and opinions, Goodwin spoke about his love for science, the growing interest in environmental issues, and his philosophy on cell phones.

“This,” he said, pointing to his mobile device, “is the enemy of the world.”

How did you develop an interest in science?

I enjoyed being outside, surrounded by nature. Growing up in Vermont, I vividly remember a sense of commune with the outdoors, the forest, and trees. This was pre-cell phone and cable television. I just loved the bigness of it all. I was always into biology and as I grew older, I developed interests in geology and paleontology.

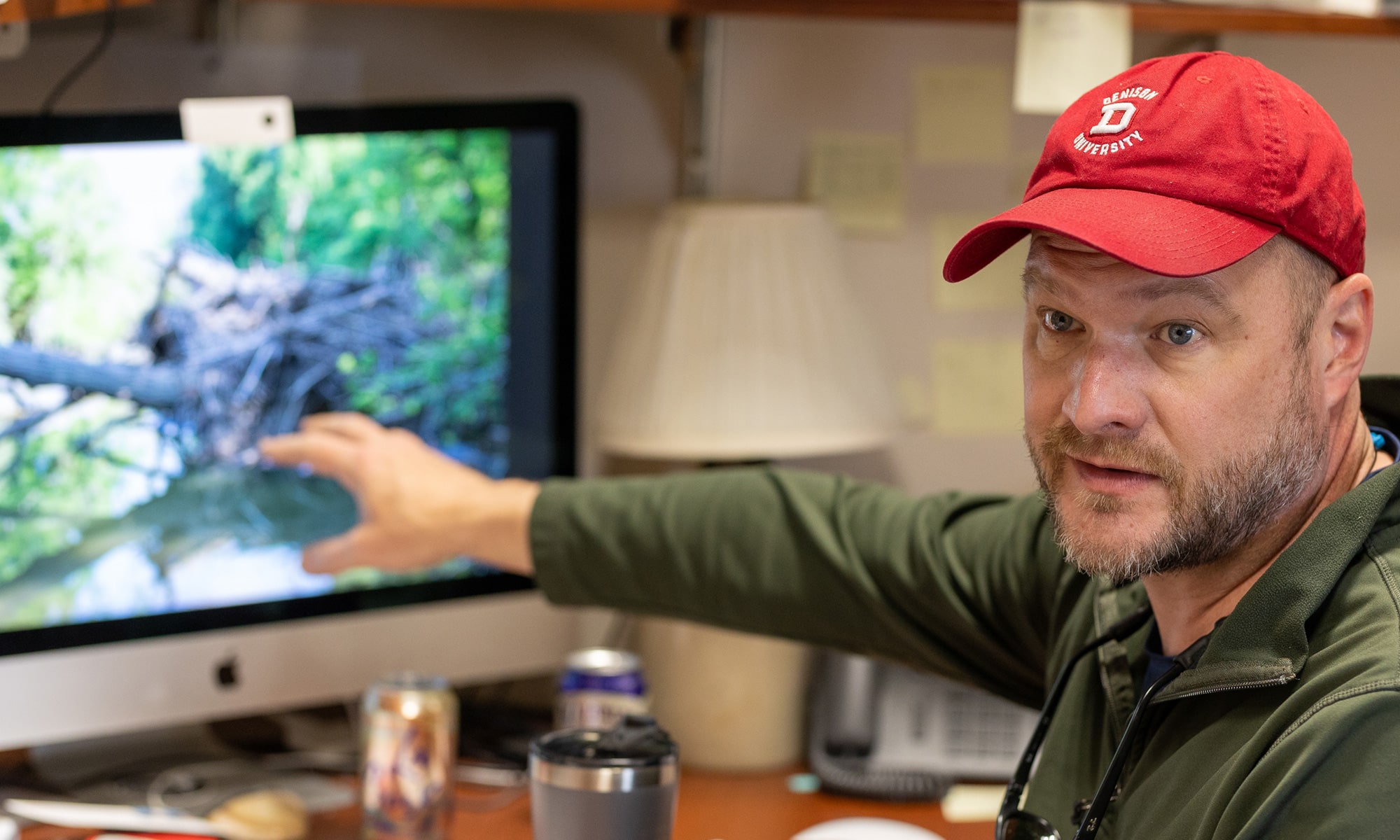

David Goodwin points to an image of Raccoon Creek on his computer screen. It’s where Summer Scholars research will take place in 2023.

Do students studying environmental science today fit the same background?

Oh, no — there are more students from different backgrounds than I’ve ever seen, which is cool. It’s not just the outdoorsy, flannelled types. Thanks to Denison initiatives, we’re bringing more diversity into environmental science, and that’s a good thing. Except I have to update my metaphors. I used to talk about thermal stratification in the water, and I would always say, “You guys remember jumping in quarries when you were a kid?” I had one kid look at me and say, “What’s a quarry?”

What was the impetus for the program rebrand?

We’ve always been environmental sciences in the sense that the things we teach are consistent with what an environmental science degree is anywhere else. By calling ourselves a geology department, we sort of pigeonholed ourselves. Most people would think of geology as an extractive science — how do we get something out of the Earth and turn it into something of value? We wanted to be less part of the problem and more part of the solution — at least in how we were perceived.

Some evidence for this is we only added one new course. We didn’t ditch a bunch of classes and then say, “We’ve got to invent a whole new curriculum.”

David Goodwin and Caroline Lopez ’25 share a laugh in the lab. Lopez is part of the 2023 Summer Scholars program.

How are the times changing regarding this field?

Traditionally, geology was not the science in high school that kids — ones who were identified as having a lot of aptitude in the sciences — were placed in. That was AP Biology, AP Chemistry, or AP Physics. This meant that we were sort of a “found major.” Kids would take a geoscience class and they would say, “You guys are doing cool stuff, and the field trips are a lot of fun.” Now, because lots of kids take environmental science as an AP course, they sort of know us already, or at least they think they do.

You have been part of many field trips at Denison. What is the value in them?

You teach what you teach in the classroom, and then you go out and you try to apply it in the real world. That’s when students really learn the material. We teach them all this cool stuff about certain rocks in the Bahamas, but then you go to the Bahamas, and you can hold the rocks and you can feel them under your toes.

So do you have a problem with cell phones?

I suppose I don’t have a problem with cell phones, per se. Rather the constant connectivity offered by smart phones is seductive — in a bad way. How’s this for liberal artsy? Cell phones are to students what the Sirens were to Odysseus. The problem is that our students don’t know how to tie themselves to the proverbial mast. I think the constant presence of phones in our students’ lives prevents them from being present in the real world.

What’s worse is that too many of them don’t know that they are missing out on actual experiences. I can’t tell you how many times I walk into a room before class to find all of my students sitting in silence with their heads bowed, and I say something like, “You won’t find any answers in there. The real world is up here with us.”